From “Everyday Tomorrow,” by Stephen Mayes:

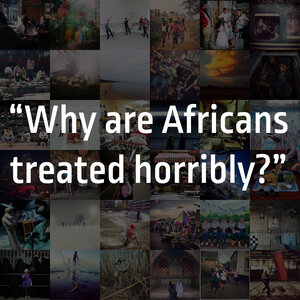

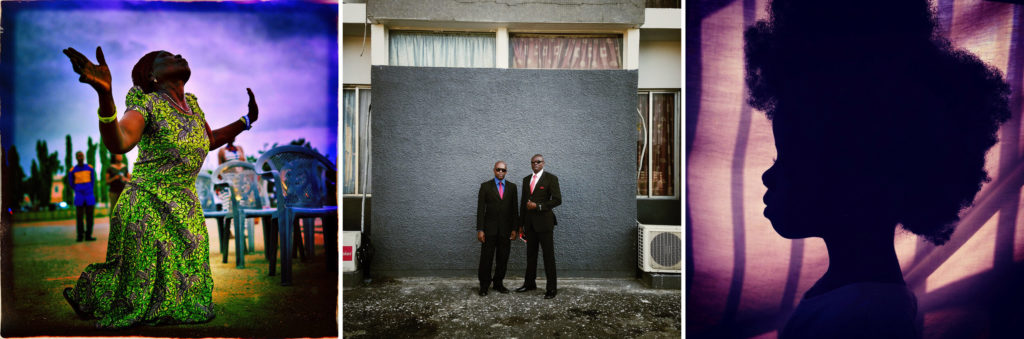

“...the online stream quietly yet insistently subverts expectations of what is noteworthy and remark- able about Africa and indeed the very nature of photography and how we’re used to seeing the world through the lens of a camera. In this book, the everyday is bound and made collectible in a process that imbues the most ordinary events and images with significance that may not yet be visible, but which to these same eyes in twenty years will look completely different. It’s a rare opportunity for our future selves to look back at a way of seeing that will have disappeared, as online platforms evolve into new forms or succumb to pressures that force them dark.

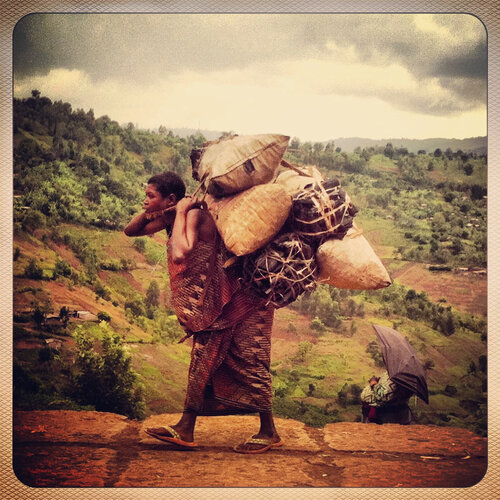

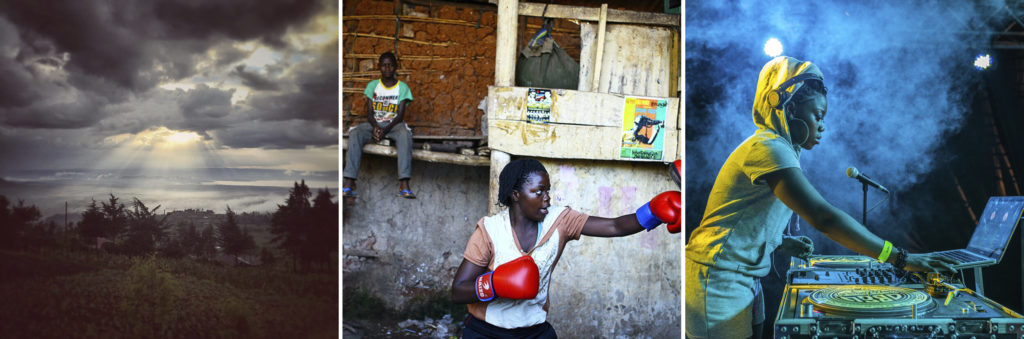

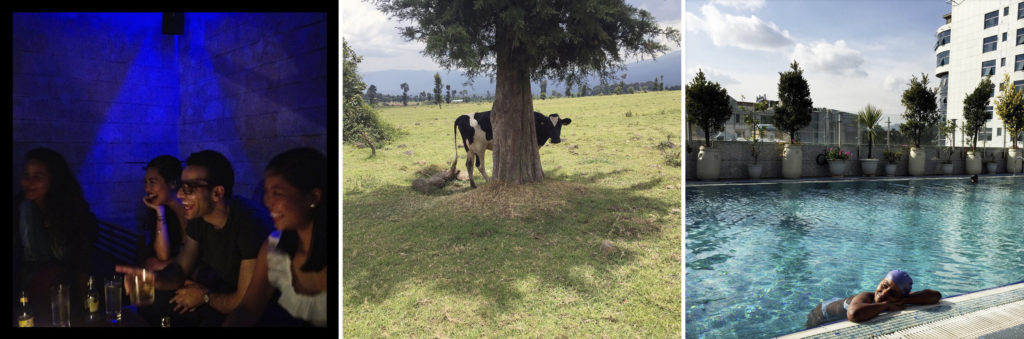

What will we see with these eyes of the future, as we look back at the casual observations gathered here from the cities, towns, and villages of early twenty-first century Africa? The beauty of the images will survive, and that will suffice to satisfy many; for that alone this book will have a justified place in history. For the more curious who delve into the comments pulled from the live Instagram experience, there may be astonishment that an iPad in the hands of a schoolchild in Ghana could cause such surprise, or that three women carrying produce through a Kigali street could lead to a discussion of truth versus reality. These are everyday circumstances that, in the context of their original publication, reflected the co-existence of traditional and modern practices across the continent and simultaneously exposed prejudices and sensitivities fostered by decades of postcolonial media. Historians opening this book will see evidence of how the mobile phone camera changed popular understanding of the world, shaping knowledge and attitudes in ways that weren’t immediately obvious as the changes were happening. Everyday Africa brings all these phenomena to the fore, and the book exposes them like a flare that illuminates a brief moment, allowing scrutiny even as the images on the feed fade away.”

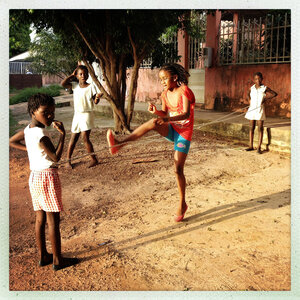

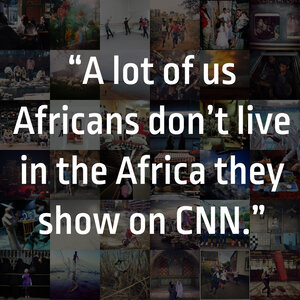

“Approaching Everyday Africa with misaligned expectations is disconcerting, much like looking through a telescope from the objective lens instead of the eyepiece. ‘Where did everything go? Where is the Africa I know from every other photograph I’ve seen?’ This frustrated expectation is revealed in the anguished comments of Instagram viewers seeking to impose old world order on new world imagery. A child bathing in a puddle must represent poverty and can’t only be seen as a specific child’s enjoyment as they play in water (which, understood as a detail of individual experience, is common to rich and poor around the world). Our perspective has been so distorted by decades of strictly formatted media reporting on Africa that sometimes we can no longer see what we’re looking at.

The use of stereotype to tell the story of many by telling the story of a single symbolic figure has bred a blindness to the individual, and the legacy of this media trope is a confused tangle of conflicting perceptions. In the old way individuals are obscured because they are seen to represent the lives of others. Removing the expectation of stereotype reveals individuals in a more personal light. In fact, symbols of distress that are traditionally assigned by photojournalists are not necessarily evident in the everyday lives of even the most anxious people—to an eye trained to seek cues of despair, significant social issues may not be apparent at all. It takes careful study to find refugees in these pages, or the hardship of unemployment, or the impact of HIV, homelessness, or homophobia, but it’s all here amidst the wedding anniversaries, shopping lines, and bathers. Stress and distress mingle with joy and fulfillment because they are embodied in the same people. The limitation of traditional reporting has been to assign a single role to each individual, whereas in life we each know many roles.

On Instagram, Everyday Africa contains all these experiences side by side in a narrative that is confused and coherent all at once, with neither beginning nor end, looking much like life itself. Delighting in the moment, each online image exists only in the present as part of the endlessly rolling river of Instagram impressions. Each new post is carried down that river, soon out of sight and out of mind, an unusually titillating flotsam that stays with us only long enough for a quick “like” or hashtag before the next provocation arrives.”

“With all of this wrapped between the covers of this book, Everyday Africa makes a simple but emphatic statement: The truth is rarely pure and never simple, and we do ourselves a disservice by allowing others to distill complicated reality into easy summaries. It is our responsibility to look, think, and learn. Hopefully, our future eyes will look at this with new wisdom and consider it to be a pure and simple truth.”

Discussion questions:

Mayes writes about the expectations people have when looking at photographs made in Africa, expectations born of stereotypes that represent “the story of many by telling the story of a single symbolic figure.” What would people expect if they were to look at photographs of your life? Are there elements of your daily life that could fit into stereotypes? How could you make images about your life and/or community that would tell a more complete and true story?

How do you think people will think of Africa in 100 years? Will the continent still be burdened by the stereotypes that are so prevalent today? Is it possible that photography could help change this trajectory?