Malcolm Daniel

Senior Curator, Department of Photographs, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Malcolm Daniel,

curator in charge of The Met's Department of Photographs

A respected curator and scholar of photography, Malcolm Daniel has been an integral part of building The Met's collection for over 16 years. As Senior Curator of the Photography Department, Daniel is presently devoting himself to an in-depth exploration of 19th and early 20th century photography. He started his career at the Met working with Maria Morris Hambourg, who brought in important photographic collections. During that time, The Met's photography collection grew into a major force. As Curator in Charge, Daniel continued in Hambourg's tradition in his own right. He worked to expand the museum's Department of Photographs to include exciting works in new media and putting the Department's entire collection on the museum's web site. Daniel talked with PhotoWings about the evolution of The Met's photography collection, his mentorship under the legendary Maria Morris Hambourg, the power of photography, how the museum managed to acquire the some of its most extraordinary collections, and its ever-evolving plans for the future.

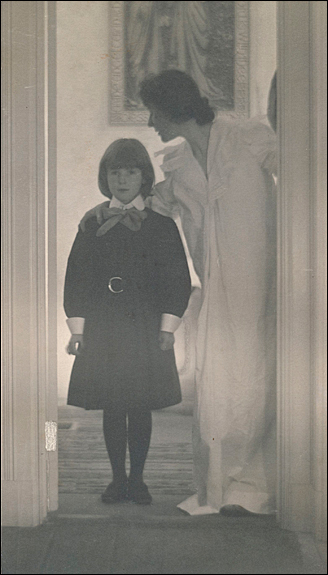

Click here to learn about one of the Met’s most important photographic collections: The Diane Arbus Archive. Decades after her death, Arbus continues to be both revered and reviled for her compellingly intimate, and often troubling portraits.

~ The Diane Arbus Archive at the Metropolitan Museum ~

In 2007, The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Department of Photographs acquired an extraordinary addition to its respected collection. The archive of Diane Arbus (1923-1971), one of the most recognized and controversial photographers of the late 20th century, is an amazingly complete and well-preserved record of the life, work, methodology and inspirations of a woman who is known as much for her powerful, intimate and often troubling portraits of society’s outsiders, as for her striking and insightful views of everyday people. Jeff L. Rosenheim, Curator in Charge of The Met’s Department of Photographs and the motivating force behind this new acquisition remarked that “The Diane Arbus Archive will provide a contextual understanding of Arbus’s stunning achievement with the camera, and simultaneously offer fundamental insight into what it means to be an artist in modern times.”

PhotoWings: I'd like to start off by asking how you happened to become a curator.

Malcolm Daniel: I've always been interested in museums. I grew up in Baltimore. When I went to college, I was both a studio art and art history major and, as time went on, I became less convinced of my own artistic talent. The more great art I saw by other people, the more humble I became about my own, and the more interested in what other people were doing.

After college, I came back to Baltimore and ended up getting a job in the Education department of The Baltimore Museum of Art, running the school tour program. I had a great group of volunteer docents who taught me many things, and whom I was able to teach also. At that time, they did not have a strong photography collection. But I was also very much interested in the 19th century French print collection that they have there, which is a world-class collection. I had been a printmaker in college so I was particularly interested in the graphic arts, and I was interested in contemporary art because they had a great chief curator at the time, Brenda Richardson, who was doing exciting shows that ranged from Frank Stella's black paintings to Mel Bochner, to Gilbert and George, to Bruce Nauman.

So after being at the Baltimore Museum for four or five years, I really felt the desire to learn more and ended up going to Princeton. I was very excited by the work I was doing with an art historian named Tom Crow at the time, [former] director of the Getty Research Institute who was at that time writing about 18th century French painting - a brilliant art historian.

But I probably would have been a really third-rate Tom Crow. He was somebody whose knowledge and way of thinking was very much connected to social history. He was able, in a very meaningful way, to tie the art that he was looking at to that knowledge and that perspective. I don't think that came as naturally to me. In the end, when Tom did not get tenure at Princeton and then went on to a brilliant career elsewhere. I had to decide; was I going to follow him to other universities and try to do what he did so well, or was there another path?

Photo History: A Wealth of Discoveries

By that time, I had taken a few seminars in the history of photography with Peter Bunnell who had been at Princeton for a long time and really established Princeton as a place where one could study the history of photography. He held what (may have been) at the time the only endowed chair in history of photography at a university, set up by David McAlpin. And Peter had really built a program and a collection that he could teach from. And one of the things I found so exciting about my work in those seminars was doing primary research. At the time, Peter had acquired for the museum the archives of both Clarence H. White and then Minor White. And Peter had studied with Minor White, and Minor had been a mentor to him, so eventually the collection - all the proof cards and the negatives and prints and writings - these all came to Princeton, so there was this archive there.

One of the things that's so exciting about photographic history [is] that there's so much to discover and to present for the first time to the public ... I remember at the time of the Baldus show, people said, "Who is this guy? How come I've never heard of him?" The pictures were manifestly interesting, beautiful, ambitious, powerful pictures. And yet, the name was completely unknown to even the art-interested public. That's how I got to be a curator.

The excitement of working with primary materials and trying to solve certain problems and being able to go in to find the answers there among the real material, instead of in secondary sources, was really an exciting thing. I realized that there were great artists about whom very little had been written. So at a certain point, I decided that I would stay at Princeton and see if there was a way to combine my interest in 19th century French art with photography. I ended up doing my dissertation on the French photographer of landscape and architecture, Édouard Baldus, about whom there was one article at the time.

In photography, there are artists of absolutely the highest tier about whom little research has been done. That's exciting. It's exciting as a curator, as a researcher, as a writer. Hopefully it's exciting for the public to come in and have that experience.

![Roger Fenton (English, 1819–1869) [Rievaulx Abbey, the High Altar], 1854 Albumen silver print from glass negative, 29.5 x 36.7 cm (11 5/8 x 14 7/16 in.) The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gilman Collection, Purchase, William T. Hillman Foundation Gift, 2005 (2005.100.275) Image © The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York Roger Fenton (English, 1819–1869) [Rievaulx Abbey, the High Altar], 1854 Albumen silver print from glass negative, 29.5 x 36.7 cm (11 5/8 x 14 7/16 in.) The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gilman Collection, Purchase, William T. Hillman Foundation Gift, 2005 (2005.100.275) Image © The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York](../wp-content/uploads/2012/10/Fenton_Rievaulx_Abbey_575.jpg)

Roger Fenton (English, 1819–1869) [Rievaulx Abbey, the High Altar], 1854 Albumen silver print from glass negative, 29.5 x 36.7 cm (11 5/8 x 14 7/16 in.) The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gilman Collection, Purchase, William T. Hillman Foundation Gift, 2005 (2005.100.275) Image © The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

And for me, it remains one of the things that's so exciting about photographic history, that there's so much there to discover and also to present for the first time to the public and have them feel that same sense of discovery. If you're a graduate student now and you're interested in 19th century France and painting, you could work on a 19thcentury painter who's of the third rank about whom nothing is written, which is a very satisfying way to spend the next half dozen years of your life. Or you can pick somebody who is truly a great painter like Edouard Manet and spend the next five years reading what everybody else has already written. And maybe, if you're smarter than everybody else, you'll have something new thing to say.

In photography, there are artists of absolutely the highest tier about whom little research has been done. We think the person's already been done if there's a catalog on Gustave Le Gray or Édouard Baldus. They're not. There are many great photographers about whom there's a single book or no book. So that's exciting. It's exciting as a curator, as a researcher, as a writer. Hopefully it's exciting for the public to come in and have that experience.

![Gustave Le Gray (French, 1820–1884) [Oak Tree and Rocks, Forest of Fontainebleau], 1849–52 Salted paper print from paper negative, 25.2 x 35.7 cm (9 15/16 x 14 1/16 in.) The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Purchase, Jennifer and Joseph Duke and Lila Acheson Wallace Gifts, 2000 (2000.13) Image © The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York Gustave Le Gray (French, 1820–1884) [Oak Tree and Rocks, Forest of Fontainebleau], 1849–52 Salted paper print from paper negative, 25.2 x 35.7 cm (9 15/16 x 14 1/16 in.) The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Purchase, Jennifer and Joseph Duke and Lila Acheson Wallace Gifts, 2000 (2000.13) Image © The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York](../wp-content/uploads/2012/10/Le_Gray_Oak_Tree_575.jpg)

Gustave Le Gray (French, 1820–1884)

Oak Tree and Rocks, Forest of Fontainebleau, 1849–52

Salted paper print from paper negative, 25.2 x 35.7 cm (9 15/16 x 14 1/16 in.)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Purchase, Jennifer and Joseph Duke and Lila Acheson Wallace Gifts, 2000 (2000.13)

Image © The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

I remember at the time of the Baldus show, people came in and said, "Who is this guy? How come I've never heard of him?" The pictures were manifestly interesting, beautiful, ambitious, powerful pictures. And yet the name was completely unknown to even the art-interested public. That's how I got to be a curator.

Mentored by Maria Morris Hambourg

Malcolm Daniel: So how did I end up being here? As I started to work on my dissertation, I had a fellowship here at The Met for a year, and Maria Morris Hambourg was the photography curator. There was not yet a photography department. She was a photography curator in the Prints and Photographs department, and she was interested in what I was doing. I admired the work that she had done, and so I had this opportunity for the year. And she got to know me and I got to know her. I went off to Paris to do a year's worth of research and, in the course of that year, her assistant left and the position became available, and I stepped into that position as a curatorial assistant 16 years ago and just rose through the curatorial ranks.

Maria Morris Hambourg really built the department. She did important exhibitions. She wrote great catalogs. She was famous for her wonderfully poetic labels, for her impeccable sense of how to mat the pictures, hang the pictures, interpret them, frame them-how to orchestrate that experience. You know, for many years I thought of my job as sort of assisting the master.

PhotoWings: When did you become the head curator?

Malcolm Daniel: I became Curator in Charge a few years ago.

PhotoWings: How did that change come about?

Malcolm Daniel: Well, Maria Morris Hambourg, who came to the museum in 1985, really built the department. She built the collections and built the staff and convinced the director and trustees to establish an independent curatorial department of photographs, which was founded in 1992.

She did important exhibitions. She wrote great catalogs. She was famous for her wonderfully poetic labels, for her impeccable sense of how to mat the pictures, frame the pictures, hang them, interpret them - how to orchestrate that experience. You know, for many years I thought of my job as post-graduate vocational training, sort of assisting the master.

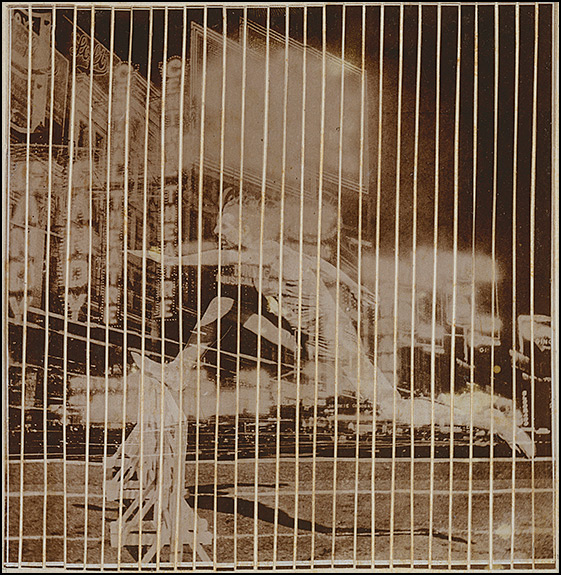

El Lissitzky (Russian, 1890–1941)

Runner in the City, ca. 1926

Gelatin silver print; 13.1 x 12.8 cm (5 3/16 x 5 1/16 in.)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Ford Motor Company Collection, Gift of Ford Motor Company and John C. Waddell, 1987 (1987.1100.47)

Image © The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

About seven years ago, she and her husband adopted twins, a boy and a girl, from Vietnam. She took a leave of absence and then came back just part-time. And at that point, I was an associate curator and the administrator of the department, which meant that I took care of a lot of the budgets and the personnel issues and things that weren't actually very fulfilling personally for Maria anyhow. And so she remained the Curator in Charge. Then at a certain point, she felt it was better for her and for the stability of the department if she stepped aside in a consulting curatorial role and I became the head of the department. It was, of course, the director's decision, but it was certainly because of Maria's recommendation that I succeeded her.

[Maria Morris Hambourg has] got an incredibly sharp eye and visual memory. I think she was confident of her knowledge and also confident of her belief in the importance and power of photography to win people over, including our director and our trustees, to make The Met a place that people now look to for photography.

I became the head of the department and she's remained affiliated with the department. She's a research scholar now, so she keeps a tie to the department. And it is certainly my hope that, as time goes on, she'll miss us enough that she will want to do some writing or exhibitions or help us out more with cultivation of collectors or be our eyes and ears out in the galleries and let us know of things she thinks are interesting. I think that we certainly all feel here that much of who we are as curators is owed to Maria's inspiration and knowledge of teaching, that if she's willing to give more, we're willing to take more, [that we] still have things to learn.

PhotoWings: What was it about the force of her personality that she was able to accomplish all of this?

Malcolm Daniel: I think she's got an incredibly sharp eye and visual memory. Brilliant intellect; she writes exceedingly well with a force of personality. I think she was confident of her knowledge and also confident of her belief in the importance and power of photography to win people over, including our director and our trustees, to make The Met a place that people now look to for photography. And [she has] a huge amount of energy.

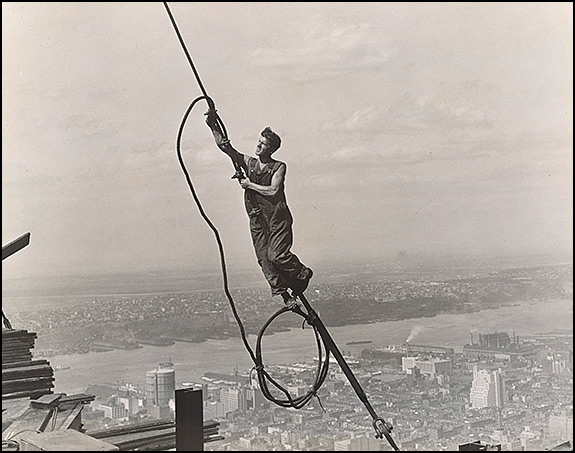

Lewis Hine (American, 1874–1940)

Icarus, Empire State Building, 1930

Gelatin silver print, 18.7 x 23.7 cm (7 3/8 x 9 5/16 in.)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Ford Motor Company Collection, Gift of Ford Motor Company and John C. Waddell, 1987 (1987.1100.119)

Image © The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

How The Met Acquired The Gilman and The Ford Motor Company Collections

PhotoWings: How did Maria Morris Hambourg handle disappointment?

Malcolm Daniel: Well, there weren't a whole lot of disappointments. I think she kept going. For instance, our acquisition of the Gilman Collection, which has happened only very recently. She had that on her mind before she came to The Met in 1985.

She tells the story of her job interview with Philippe de Montebello (Former Director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art). Philippe asked her for her frank assessment of The Met's photography collection and she said, "Well, in certain areas like the Photo-Secession, thanks to the gifts of Alfred Stieglitz, The Met is very strong. In other areas, so-so." And he said, "Well, what would you do about it?" And she said, "Well, there are two collections out there that really ought to come to The Met. One is a collection of avant-garde photography between the two World Wars in Europe and America, about 500 pictures put together by a New York collector named John Waddell. And the other is one that's being put together by a man named Howard Gilman and his curator Pierre Apraxine, and it's a brilliant, growing collection of masterpieces from the first 100 years of photography." Maria says that Philippe looked at her and said, "Well, get to work." So she did.

John Waddell's collection was acquired in 1987, known here as The Ford Motor Company Collection because Ford was the major donor that made the purchase gift arrangement for that collection possible. And there was a great show of that on the 150th anniversary of photography in 1989 called The New Vision.

John Waddell will tell you to this day that he has never had an experience like the experience of working with Maria on refining the collection and then putting the exhibition together. I don't think it was hard to convince him that The Met was the place and she was the curator for his collection.

And the Gilman Collection took 20 years to acquire. We did a major exhibition that you may remember called The Waking Dream in 1993. It was the first time that photography was in the special exhibition galleries-the grand, neoclassical galleries at the top of the grand staircase, galleries that are usually reserved for Velasquez and Rembrandt. It was a big thing to have photography in those galleries. It was a show that many people considered the most beautiful show of photography that they've ever seen. It was beautifully designed. The works are just of incomparable beauty. So that was a big thing, and we thought at the time that perhaps Howard Gilman would announce a gift or promise a gift and it didn't happen.

Howard configured in money for a gallery to be built that opened in fall of 1997, devoted exclusively to photography, the Gilman Gallery. We thought that might be a time when a gift would be made, and then he died suddenly at the very beginning of 1998. So then it took us from January of 1998 until February of 2005 in negotiation with Howard's executors and the board of the Howard Gilman Foundation, which was his principal beneficiary, to work out a purchase gift arrangement to bring the whole collection to The Met. And it was a very painful process, and a huge task of fundraising, and a huge commitment from our trustees and director, and our supporters.

So there were certainly disappointments along the way if Maria hoped to get it in 1993. Dealing with disappointment meant you just said, "Okay, what do we do now in order to accomplish that goal? Let's not give up on the goal but just keep going." But I would say that she managed to do most of the things she wanted to do. There weren't a lot of disappointments on the way. It's been a period of increasing presence for photography at The Met.

PhotoWings: So how did she go about convincing these people? What was her style?

Malcolm Daniel: She already had a relationship with John Waddell and with Pierre Apraxine. She was working at MoMA at the time, so she knew these people and she had a lot of respect for what they were doing, but they had a lot of respect for her too. So that relationship was already forged. And John Waddell will tell you to this day that he has never had an experience like the experience of working with Maria on refining the collection and then putting the exhibition together. I don't think it was hard to convince him that The Met was the place and she was the curator for his collection. There was money to be raised, still. Part of it was a gift from John Waddell, but there was money to be raised and that's where Ford eventually came in. There was a particular person with an interest in photography and the ability to direct corporate philanthropy our way.

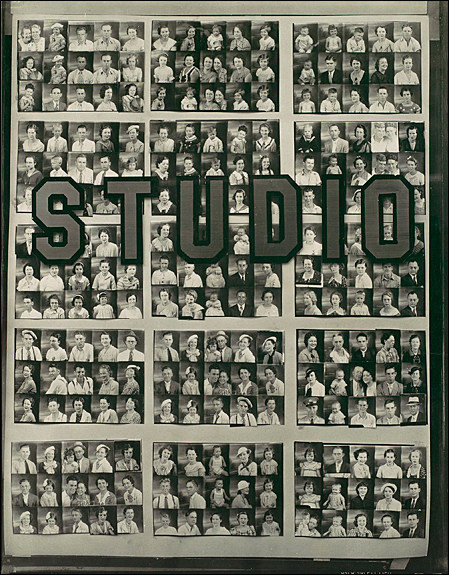

Walker Evans (American, 1903–1975)

Penny Picture Display, Savannah, 1936

Gelatin silver print, 24.7 x 19.3 cm (9 3/4 x 7 5/8 in.)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Ford Motor Company Collection, Gift of Ford Motor Company and John C. Waddell, 1987 (1987.1100.482)

Image © The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Corporate Donations: Giving the Public Access to Privately Held Art Collections

PhotoWings: So how was Ford able to justify donating money for this collection for the museum? Why was it good for them?

Malcolm Daniel: That's a question for them, but certainly to this day, the collection as a whole - and every picture in it - bears their name. And the show traveled to cities around the country and actually around the world with their name. What made it different was that it was for support of an acquisition rather than an exhibition.

But you can ask the same thing about any corporate sponsorship of an exhibition. What do they get out of it? It's serving the public. It's helping to enrich one of the great art institutions in the world and to make this material that was in a private collection available to the public through exhibition, through our study room, through publication.

Great works of art have the power to move us, whether they're made now or whether they were made 50 years ago, 100 years ago, or 1,000 years ago or more. And so each time we lose something that has that power, we've lost an opportunity to be changed by it.

Preserving Our Photographic Heritage

PhotoWings: Why should people care about saving their photographic heritage?

Malcolm Daniel: I think the question has its answer right in it - it's part of their heritage. From a historical standpoint, there are things to be learned from the past. From the standpoint of a more spiritual aspect or just beauty, great works of art have the power to move us, whether they're made now or whether they were made 50 years ago, 100 years ago, or 1,000 years ago or more. And so each time we lose something that has that power, we've lost an opportunity to be changed by it. I don't think it's inherently different than preserving some other aspect of the past. We lose writings. People throw photographs out in the garbage and you no longer have that sort of family history. I don't know that it's any different than throwing out the diaries and the letters that are part of that family history, too. You know, if you lose it, you lose it.

Click here to learn about The Met's remarkable acquisition: The Diane Arbus Archive. Decades after her death, Arbus continues to be both revered and reviled for her compellingly intimate, and often troubling portraits.

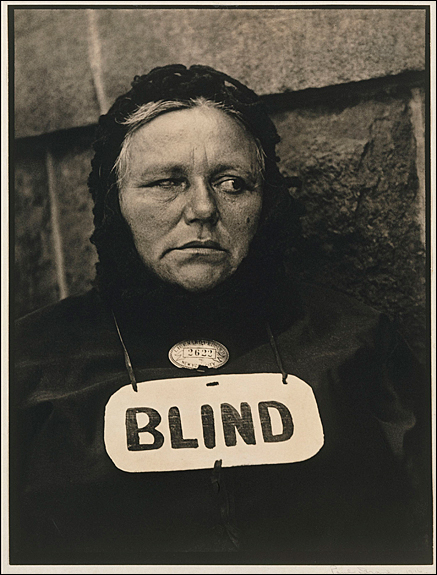

Paul Strand (American, 1890–1976)

Blind, 1916

Platinum print, 34 x 25.7 cm (13 3/8 x 10 1/8 in.)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Alfred Stieglitz Collection, 1933 (33.43.334)

Image © The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Curating: Is Photographic Experience Necessary?

PhotoWings: I'm curious. Are you a photographer as well? And do you think that there's a difference between curators who are photographers and who aren't photographers?

Malcolm Daniel: I'm not a photographer and I never was. In high school, I puttered in the darkroom and I understand the basic process. I'm not a photographer. I do think that I'm a better art historian for having also tried to be an artist in college and I think, for instance, my knowledge of printmaking helps me understand things like photogravure and photolithography and various photomechanical processes more clearly than someone who hasn't done that. And I'm sure that if I had been a photographer and I understood better the optics of various lenses and things like that, I probably would understand pictures in a different way, too. I might understand those choices that a photographer makes.

Jeff Rosenheim comes out of having been a photographer. His background is as a photographer and in American studies. Mine comes really out of art history. So we have different perspectives, and that's complimentary within the department. It's nice to be able to turn to somebody and say, "What's going on here? How does the person do that?" On the other hand, maybe I am able to make some connection to art in another medium that might not be as evident to him. So we work well together.

Educating Our Photo Historians

PhotoWings: Why are there so few places for photographers to study photographic history?

Malcolm Daniel: I just think it's a young discipline. It's only been in recent years that people really thought about the history of photography and it just takes time to develop - for people to be trained and to go back into academia and to train the next generation.

I think, also, the more presence photography has in museums and in the public mind or public interest, the more people are interested in studying its history. There aren't that many places, still. If you want to study the history of photography at the graduate level, there are a handful of places, really.

The Magic of Photography

PhotoWings: Why is it said that a picture is worth a thousand words? And what is unique about the way it informs the viewer?

Malcolm Daniel: It sounds silly to say, but I think photographs actually do have some sort of magical power over most [people]. We may mock people who think that the camera captures the spirit of the person. It's the sort of stereotype of the primitive civilization that thinks that their soul has been captured in the piece of paper, but it has in a way. It doesn't mean it's taken away from the person, but there is something about a photograph - say, a photographic portrait - that is different than a painted portrait, no matter how beautiful.

The painting has the beauty of the brush stroke and the sort of visible expression of the picture maker there. But even the most humble snapshot of somebody you love has a quality that is hard to explain. I think you would be hard-pressed to follow my instructions if I asked you to take out of your pocketbook a picture of someone you love - a child or a wife or husband or parents - and to rip it into little bits, even if you had another copy of it. Would you want to put little pins through the eyes of the picture even if you had another copy of it? No. It's just a piece of paper, but you feel that there's something there despite your dismissal of superstition, and somehow you feel that picture has a quality of the soul there.

There is something about a photographic portrait that is different than a painted portrait, no matter how beautiful. That painting has the beauty of the brush stroke and the visible expression of the picture maker there. But even the most humble snapshot of somebody you love has a quality that is hard to explain.

There's somebody who says, "I would rather have the most humble picture of someone I dearly loved than the finest work of a great master." I think if you have the chance to have one photograph in your life and there was a choice between a photograph of a loved one or a great photograph by Julia Margaret Cameron, you would probably pick the one of the person that you love because there's a spiritual connection there, and I think photography has that. It's just in the nature of photography. We know that photography doesn't always tell the truth, but there is a feeling of authenticity and of connection.

PhotoWings: What is it about the essence of photography that has the power to bring about change?

Malcolm Daniel: I don't think that photography is unique in its ability to evoke emotion and cause change. I think that's what this museum is about. I think that's what art is about. I think one can stand in front of a great painting or a classical sculpture or a Chinese landscape scroll or an African mask and be moved spiritually or feel emotion. And I think that's what great art does. I don't think photography has the only claim on that. I think great photographs can do that, but I think other kinds of art do it too. And I think there's a quality about photographs which is what I described - its connection, this feeling that there's something about what's depicted that remains in that picture.

We know that photography doesn't always tell the truth, but there is a feeling of authenticity and of connection.

PhotoWings: How about causing change, such as Lewis Hine or Jacob Riis?

Malcolm Daniel: Well, I think those are very direct examples. In a way, photography for them was a tool used with great artistry, but a tool to accomplish certain ends. I think other things have the power to change too.

My heart is back in the 19th century. Nineteenth century French and British photography is what my area of expertise is and what makes my heart flutter. And for me, there's a connection when we look at photographs from the 1850s. For instance, I'm working on a show right now with guest curator Roger Taylor that focuses on British calotypes, so photographs from paper negatives made in the 1850s when people had the choice of using glass negatives or paper and they chose paper. There was a certain kind of person that chose that. It was often a gentleman-amateur. They preferred the aesthetics of that sort of fuzzy paper negative over the crystal clear glass. And it set them apart, in sort of a class way, from the trade - from the people that ran the photo studios and such, which were almost always glass negatives.

I think - I hope - that when people come to this, they are moved. Their lives change. Their actions change. The world becomes a better place because people take those same lessons that for all of the pressures of the big city and the modern life and the fast pace that there is something enriching personally, and something to be learned about our relations with the rest of humankind and with our planet through looking at these pictures and thinking about how they react and how the photographers reacted when they first saw them.

What did they photograph with the paper negatives? They photographed nature studies, geological formations, ruins, landscape, travel, loved ones, family, and things about their own life. If you set that against what was going on at the time - the 1850s were in the midst of the Industrial Revolution and burgeoning cities, London and Edinburgh and Newcastle and Manchester and Leeds and Birmingham - I think that people found an antidote to the ills of modern life, the pressures of modern society, in the contemplation of nature, in the company of family, in the meditation upon the passage of time as they looked at ruined abbeys that were once the great works of man.

And I think all those lessons are still true. I think - I hope - that when people come to this, they are moved. Their lives change. Their actions change. The world becomes a better place because people take those same lessons that for all of the pressures of the big city and the modern life and the fast pace that there is something enriching personally, and something to be learned about our relations with the rest of humankind and with our planet through looking at these pictures and thinking about how they react and how the photographers reacted when they first saw them.

I don't think that Alfred Capel-Cure or Benjamin Brecknell Turner were trying to change the world. But I have a certain perspective which is still relevant, and for me, it's actually much more interesting, in particular being in an art museum as this is, and not particularly a photography museum. Those kinds of changes are actually more interesting to me than those where photography was used as a tool for social change in a very explicit way, because I think that's actually quite easy to understand. You show terrible conditions in which people are living. It stirs people's consciences and things can change and that's great. And someone like Hine was brilliant with the camera and he made moving portraits. I think he was an artist with the camera, but it's a more direct and quite easily understandable thing, I think.

PhotoWings: So you think it brings history to life? It makes people realize that they can lose what they know and love today?

Malcolm Daniel: Brings history to life? I think there's an aspect of that...

Certainly, we think when we look at pictures from a hundred years ago; it does stir us to think about what the world was like at a certain point. But I think it's more than just bringing history to life. This direct connection happens between seeing and feeling and living. I think that's what art's about.

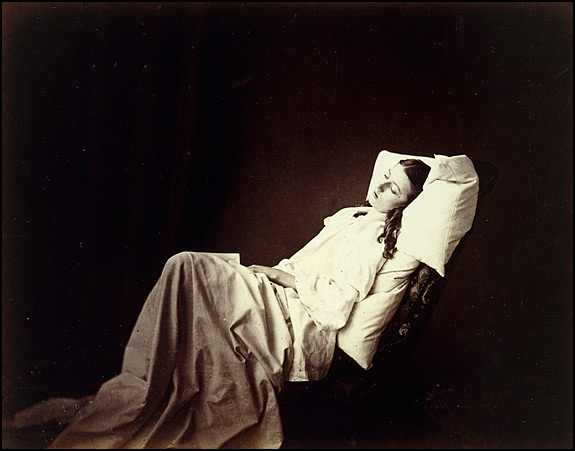

Henry Peach Robinson (English, 1830-1901)

"She Never Told Her Love", 1857

Albumen silver print from glass negative, 18 x 23.2 cm (7 1/16 x 9 1/8 in. )

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gilman Collection, Purchase, Jennifer and Joseph Duke Gift, 2005 (2005.100.18)

Image © The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

The Enduring Photograph: What Makes a Picture Great?

PhotoWings: What do you think makes a great photograph, and have those parameters changed over time?

Malcolm Daniel: Sure, I think at different points in history people looked for different things in photography. For me, sometimes it's beauty, sometimes it's a historical resonance, sometimes it's power of emotional impact, the ambition of the artist, the skill and craft with which the picture was made. The rarity of something that we are interested in.

Sometimes things feel diluted by overexposure. Nobody feels moved by the Mona Lisa anymore because they've seen it reproduced and satirized a million times. So it's awfully hard to stand in front of that and have any kind of spiritual experience. It still is a great painting. We just can't experience it as such. You're more likely to go to the National Gallery to look at the Leonardo portrait of Ginevra de' Benci there, which probably you haven't seen in reproduction a million times and be astonished by the quality of painting and the sense of soul and personality that comes through.

And so, the same is true with photographs. That's one of the reasons why rarity matters to us, is because we can provide an experience that people haven't had elsewhere. You know, as great as The Moonrise Over Hernandez is, for those of us who have been looking at photography for a long time, it's hard to see that in a fresh way. Something we haven't seen before is exciting.

I think at different points in history, people looked for different things in photography. For me, sometimes it's beauty, sometimes it's a historical resonance, sometimes it's power of emotional impact, the ambition of the artist, the skill and craft with which the picture was made.

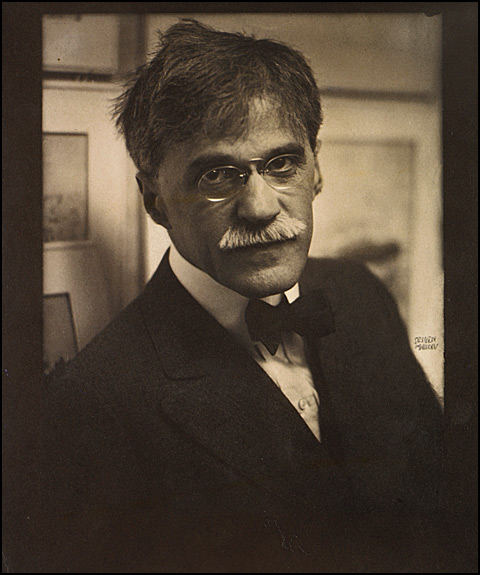

Edward Steichen (American, born Luxembourg, 1879–1973)

Alfred Stieglitz at 291, 1915

Coated gum bichromate over platinum print, 28.8 x 24.2 cm (11 5/16 x 9 1/2 in.)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Alfred Stieglitz Collection, 1933 (33.43.29)

Image © The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Dramatic Tales of Stieglitz and The Met

PhotoWings: What was the tipping point for photography to finally be considered art?

Malcolm Daniel: Oh, I don't know. It's been art since the invention and I think different people have different tipping points. There are still people who aren't convinced, I think. I don't think I can answer that. Stieglitz convinced people it was art and then there are people after Stieglitz that don't think it's art. It's something that's been debated from the moment it was born and it'll keep being debated however long. It's always been accepted as art by many people and it's always been rejected as a mechanical process by many people. I don't think there's a tipping point.

PhotoWings: Well, at some point at this museum they decided it was important to have a collection and then they gave you the big gallery.

Malcolm Daniel: Well, photography came in 1928. It didn't happen in 1992 when we became a department. It came in 1928 as a gift of Stieglitz. So, it was a dozen years after the establishment of a print department. They didn't have prints until 1916. I think these things happen gradually. I think photography is more and more a part of contemporary art. But we're not a museum of contemporary art, either. We try to be encyclopedic with our collections. And there's no denying that there is an art of photography and any representation of the creative expression of mankind, from the beginning of time to the present around the world, has got to include photography.

PhotoWings: You talked about how your collection was built. I'm curious about the people who originally assembled these special collections. Why did they feel compelled to do so?

Malcolm Daniel: The first curator of prints was a brilliant, largely self-educated man in terms of his education about prints named William Ivins who wrote a book called Prints and Visual Communication and then there's a wonderful, thin little book called How Prints Look, which is a model.

He had gone to Harvard and taken Paul Sachs' course there and had gone off to Germany to study economics or something and ended up spending all this time at the Albertinain Vienna, learning about drawing and prints.

We try to be encyclopedic with our collections, and there's no denying that there is an art of photography and any representation of the creative expression of mankind, from the beginning of time to the present around the world, has got to include photography.

He had visited Stieglitz's gallery in 1891 and knew Stieglitz and had seen the European avant-garde art that Stieglitz was showing, as well as photography. And so it was natural that he would be open to the idea of photographs as he was building a print collection.

And it was also Stieglitz's aim to place photography - particularly his own photography - at his favorite museum, the one which was the sort of temple of fine art.

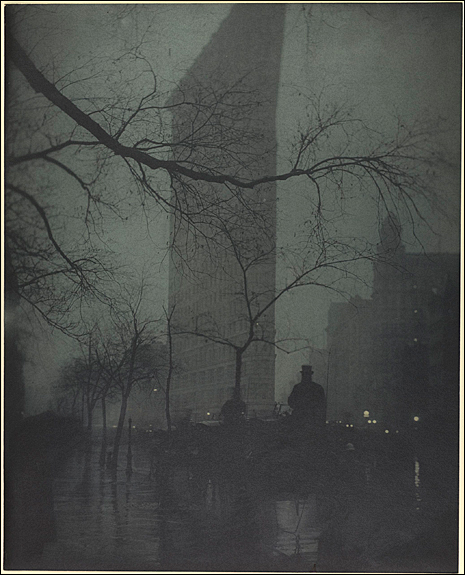

Edward Steichen (American, born Luxembourg, 1879–1973) The Flatiron, 1904, printed 1909 Gum bichromate over platinum print, 47.8 x 38.4 cm (18 13/16 x 15 1/8 in.) The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Alfred Stieglitz Collection, 1933 (33.43.39) Image © The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

And so he began discussions with Stieglitz in the '20s about The Met buying work from him. Eventually, in 1928, Stieglitz made a gift of 22 of his own pictures, which included photographs of Georgia O'Keeffe, Equivalents, landscapes, and some other portraits specially chosen for this collection. He gave them in other people's names so it didn't look like he was giving them. He could profess surprise and delight at his work having been donated to The Met. But it took several years of negotiation and Ivins convinced the board to accept the gift. And in a way, it did open the doors of The Met to photography as both of them hoped. The next year, Paul Outerbridge gave photographs to The Met.

[Stieglitz] called up to say, "If you want it, it's yours. Send the truck. You've got 24 hours; otherwise I'm putting it in the garbage." And Ivins was away and his assistant answered the phone, took the message to the director and said, "You have to do this," and called Stieglitz back and said, "The truck is on its way."

What really threw the doors open was Stieglitz's gift in 1933 of more than 400 photographs by other photographers who he had shown in his galleries and published in Camera Work. By 1933, Stieglitz was making a completely different kind of picture than what had interested him, in his own work or in other people's work, in 1900 or 1902 or 1910 or 1915 even. And so it had become something of a burden to have all these pictures, and he offered it to The Met.

He called up to say, "If you want it, it's yours. Send the truck. You've got 24 hours; otherwise I'm putting it in the garbage." And Ivins was away and his assistant answered the phone, took the message to the director and said, "You have to do this," and called Stieglitz back and said, "The truck is on its way." And Stieglitz said, "Remember, anything that you don't want, you don't have to keep, but many of these things have real pedigree." They've been sent to major exhibitions around the world, and it has stayed whole; The Stieglitz Collection.

In 1928, Stieglitz made a gift of 22 of his own pictures. He gave them in other people's names so it didn't look like he was giving them. He could profess surprise and delight at his work having been donated to The Met.

And he gave a further 200 photographs by other people by bequest. So this great core of our collection is the Photo-Secession. We're very strong from 1895 to 1915.

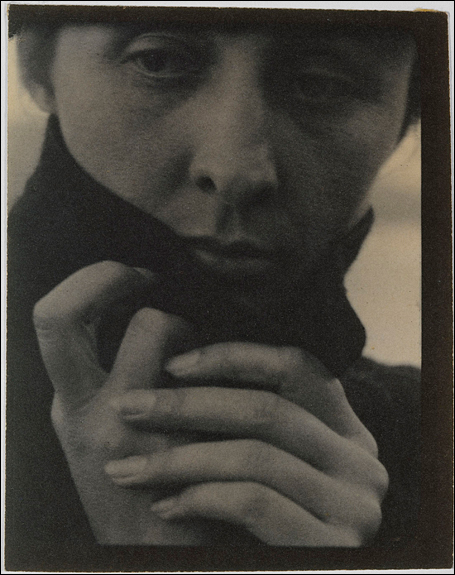

I think many people probably know the three large gum prints of The Flatiron by Edward Steichen, each a different color, as though a different moment of twilight. Those are three of many large exhibition prints by Steichen that we have from that early period. Great works byPaul Strand from around 1916, Gertrude Käsebier, F. Holland Day, Charles Sheeler, Clarence White, Stieglitz himself. And then Georgia O'Keeffe - put on deposit here and eventually they were acquired, some as recently as 1997 - about 75 of the portraits that Stieglitz made of her over a period of time.

Alfred Stieglitz (American, 1864–1946)

Georgia O’Keeffe, 1918

Platinum print, 11.7 x 9 cm (4 5/8 x 3 9/16 in.)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of Georgia O’Keeffe through the generosity of The Georgia O’Keeffe Foundation and Jennifer and Joseph Duke, 1997 (1997.61.25)

Image © The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

The Big Mistake: Losing a Collection

Malcolm Daniel: There is a story which may be apocryphal but may not be apocryphal. The Met was, of course, Stieglitz's favorite museum, and when he died Georgia O'Keeffe came and spoke to the curator of prints, Hyatt Mayor, about placing the master set of photographs here. But Hyatt Mayor also was a brilliant curator brought in, I think, in the '30s by Ivins and eventually succeeded him as head of the Prints department.

And Hyatt Mayor had a wonderfully all-encompassing sense of what constituted the graphic arts. So did Ivins...

And so they were open to photography. They also acquired many things that we couldn't hope to touch today. One of the earliest purchases was an album of photogenic drawings by Talbot from 1839 and 1840, sent to an Italian botanist friend of Talbot's named Bertoloni. And Bertoloni put them carefully in an album along with Talbot's letters. That was acquired in 1936. You know, we couldn't hope to acquire something like that nowadays. So they were open to photography and they bought some great things. They weren't photograph curators. This wasn't a photograph collection per se.

Hyatt Mayor wrote a note to the director saying that "Mrs. Stieglitz had offered us thousands of prints, but her demands for their matting and storage were so onerous that I convinced her to give us just a sampling of Stieglitz's work."

So when O'Keeffe came and said, "It would be my desire to follow Mr. Stieglitz's wishes that the master set, the best print of each picture that he made, come to The Met," Mayor listened. And she said, "There's only one stipulation. Mr. Stieglitz was very particular about how they were cropped and matted, and for him it was all part of the presentation of the work of art."

In fact, it's true that when Stieglitz made his gift in 1928, he had them matted and framed because he wanted it done in a particular way. So O'Keeffe said, "You know, it's a certain size, it's 18 by 22 inches. The window mat has to be exactly at the place where Mr. Stieglitz has put it."

And Hyatt Mayor said, "Well, that's interesting, we actually have a different system. There are certain standard sizes. There's 14 ¼" by 19 ¼". There's 16" by 22". Our boxes are that size, and that way the pictures don't move around in the box and stay safe. It's a good way to store them."

She said, "No, no. He was really very particular about this." Hyatt Mayor said, "This is what we do with our Durers and our Rembrandts and our Goyas and our Schongauers." She said, "Well, Mrs. Durer, Mrs. Rembrandt, Mrs. Goya and Mrs. Schongauer aren't here to tell you otherwise." And she gave a master set to the National Gallery. And we all cringe now at that.

And that comment may not have been true, but the fact is true. And Hyatt Mayor wrote a note to the director saying that "Mrs. Stieglitz had offered us thousands of prints, but her demands for their matting and storage were so onerous that I convinced her to give us just a sampling of Stieglitz's work."

And of course, we regret that now. But also, at the time there probably weren't 2,000 pictures by any artist in the collection, and it wasn't a photography collection. And in a way, it probably would have seemed to skew the holdings in such an inappropriate way that one can understand why Hyatt Mayor would react in that way. You know, we have 60 years of hindsight and we have photo history to teach us things.

There weren't any photo history books for Hyatt Mayor. What he knew about photography was self-taught, really. It's amazing that they collected what they did. We now have a reference library here. The books didn't exist. Teachers didn't take a history of photography course. So it's wonderful we have the things we have. And it's easy and amusing to blame Hyatt Mayor for the National Gallery's riches and our loss. But it's also understandable, I think. So they were the first two curators of Prints and Photographs: William Ivins, Hyatt Mayor.

Hyatt Mayor was succeeded by a man named John McKendry in the '60s. He was very connected to the fashion world and to Warhol, and therefore photography flourished under his brief leadership. He died quite young.

And it was Ivins who hired Weston Naef as an assistant curator, first as a graduate assistant or something and then as an assistant curator. And Weston, although he wasn't really hired as a photography person, he made it his bailiwick. He did important shows drawing on the Stieglitz collection and also exploring Western American landscape photography. And then he left to go to the Getty Museum in 1984. Maria Hambourg was hired in 1985 and she was really the first person to come in with her doctorate in history of art with a specialization in photography, to be really hired as a photography curator. That sort of catches you up.

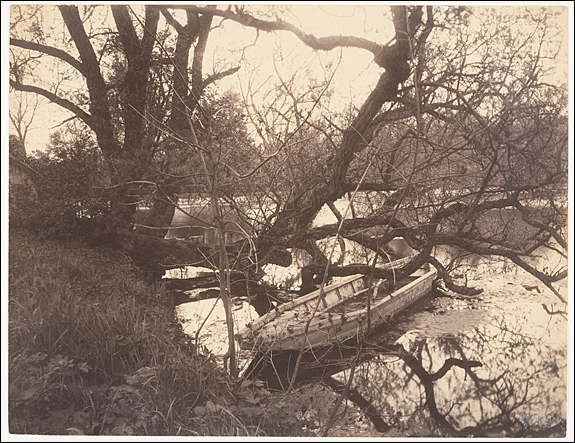

Eugène Atget (French, 1857–1927)

Ville d'Avray, 1923-1925

Albumen silver print from glass negative, 17.4 x 22.5 cm (6 7/8 x 8 7/8 in.)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gilman Collection, Purchase, Ann Tenenbaum and Thomas H. Lee Gift, 2005

(2005.100.435)

Image © The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

The Commitment of Collectors such as Howard Gilman and John Waddell

PhotoWings: How about some of these collectors, such as Gilman and the Ford Collection? What brought them to photography? Why were they so passionate about collecting?

Malcolm Daniel: With Howard Gilman, it was almost accidental. He and his curator, Pierre Apraxine—a brilliant, creative, wonderful curator—were collecting minimal art, but they had it in their offices and they realized it wasn't the right kind of art to have in the office setting. It was too much in danger. [They had] things that needed to be very pristine.

Then they began collecting visionary architectural drawings. They put together an interesting collection of that which has subsequently been given to the Museum of Modern Art. But they found that architects really didn't want to part with the kinds of drawings that they were interested in collecting.

And then they bought some 20th century photographs. Pierre had previously worked at the Marlborough Gallery and at MoMA before that. And so they bought some Richard Avedon and a picture by Diane Arbus and some Robert Frank—third quarter of the 20th century. This was in the early '70s.

[Pierre Apraxine] said, "I didn't even know who Baldus was at the time, but when you see a picture like that, you just realize it's a masterpiece." And he came back and said to Howard, "This is where we have to go," meaning early photography. I think it's because it was virgin territory, in many ways, that it was exciting.

And then they thought it might actually be interesting to have a small group of 19th century pictures that would just be an introduction to the collection. And of course, that's what ultimately became the core of the collection, the 19th and early 20th century.

Pierre tells the story of having gone on a buying trip to Paris in 1977, I believe, and having seen this wonderful picture by Édouard Baldus of a family outside. The woman's holding an umbrella up and it's almost like an impressionist picture - [actually] before impressionism, a picture from the mid-1850s. And he said, "I didn't even know who Baldus was at the time, but when you see a picture like that, you just realize it's a masterpiece." And he came back and said to Howard, "This is where we have to go," meaning early photography. I think it's because it was virgin territory, in many ways, that it was exciting. And that's still what we feel is that sense of discovery and to build a collection of the sorts of pictures that nobody else is interested in.

In the early days of the collection, the late '70s and the early '80s, there were other serious collectors. There was Phyllis Lambert and there wasPaul Walter and Sam Wagstaff and a handful of other people. There weren't many.

And most people didn't have the financial resources that Howard had and the willingness to put down record-setting amounts of money to buy the very best. And they did. They put together an extraordinary collection that included not only things that were already recognized as icons of photography, but things that nobody had seen but that Pierre and Howard recognized as having the power of great art.

PhotoWings: What did Pierre tell Howard that convinced Howard? And how did Howard think about the work?

Malcolm Daniel: I don't know the answer to that. I think Howard was certainly engaged in every acquisition. It wasn't that he just provided money to Pierre to go buy what Pierre wanted. Pierre discussed every acquisition with Howard. He had to make Howard interested, and I think Howard was interested for the same reason we're all interested in photography.

Curators, Galleries and Private Collectors: Their Symbiotic Relationships

PhotoWings: Can you talk a little bit about the different mindsets between curators, galleries, collectors, photographers? They bring different sensibilities.

Malcolm Daniel: I think everybody brings a different sensibility. We curators have a job to do. It's a different job than a private collector has and it's a different job than a critic has or a photographer.

And ours has to do with the mission of this museum, and our mission is different than other museums. Other curators have a different perspective than we have here. Our mission is here on the bulletin board: To collect, preserve, study, exhibit, and stimulate appreciation for and advance knowledge of works of art that collectively represent the broadest spectrum of human achievement at the highest level of quality, all at the service of the public and in accordance with the highest professional standards. There it is. That's our perspective.

In New York, there are a number of institutions actively collecting and exhibiting photographs. But when you go to The Met, the Modern, the Whitney, the Guggenheim, ICP, for each of us, there's a kind of institutional personality and there's a perspective of individual curators.

So when we're looking at photography, that's what we have in mind. And that's very different than the mission that a private collector may give to himself, or that a curator at a museum of modern art or a curator at a museum of photographs would have.

In New York, for instance, there are a number of institutions actively collecting and exhibiting photographs. But I think when you go to The Met, the Modern, the Whitney, the Guggenheim, ICP, for each of us, there's a kind of institutional personality and there's a perspective of individual curators. It's a different experience at these different places. And I think that's great for the public, great for the medium, great for the institutions.

PhotoWings: Could you talk a little bit about the mindset of the galleries? Is it profit-motivated specifically?

Malcolm Daniel: Well, I don't think it's an easy business to be in, and I don't think that anybody opens a gallery as the way to make a quick buck. Gallerists work really hard. There are many gallerists that struggle. I think gallerists have to love art, have to believe in their artists, and have to want to proselytize a little bit the same way that we do as curators. But it is a business and I think that does color the activities of the galleries and the choices of artists and things like that. I mean, it's different from a museum. There's no question.

PhotoWings: So what kind of influences do gallery owners and collectors have on a museum's decisions in what they acquire?

Malcolm Daniel: Well, I think there is a first culling that happens through the gallery world in particular. We see artists' work directly, but there are hundreds of photographers out there, thousands of photographers, just in New York. We can't know them all, so there's a sorting that goes on.

Since you can't see every photographer yourself, you have to trust that someone else among the hundreds of gallerists will recognize great work when it arrives on their doorstep and that it will sort of percolate to the top. So there's a sorting that happens for us a little bit. We have trouble just getting out to all the galleries. Just to keep up with all of those, let alone all of the individual photographers that are out there that don't have gallery representation... Not to say that somebody can't be good and not have found a gallery, because there's a business aspect to it too.

PhotoWings: Since galleries are out to make money, why is photojournalist and photo documentary work made by photographers - those working with Magnum or National Geographic or some of the high profile, very successful photographers - why are they seldom seen in museums?

Malcolm Daniel: Well, at the moment, we are showing an exhibition of Robert Polidori's photographs called New Orleans: After the Flood and, of course, he's the staff photographer for The New Yorker. So it's not that we don't do that at all.

I think there are other museums, for instance ICP, which have always had photojournalism as a more integral part of their mission. Our mission is to collect art here. And we don't concentrate on fashion photography, advertising photography, scientific photography, ethnographic photography, or photojournalism. Those are all aspects of the medium. There are things that we collect examples of, but they're not our primary direction.

There is a first culling that happens through the gallery world. There are hundreds of photographers out there, thousands of photographers, just in New York. We can't know them all. You have to trust that someone else among the hundreds of gallerists will recognize great work when it arrives on their doorstep and that it will sort of percolate to the top.

And, even within this museum, there are other collections of photography. The Costume Institute has a huge collection of fashion photography. The Arts of Africa, Oceania and the Americas here have a large collection of graphic and anthropological photography. We are not looking for photographs of historic things or events, which is largely what photojournalism is about. We are interested in collecting those works that represent the broadest spectrum of human achievement at the highest levels of quality. We are really looking for those great works of expression.

Saving Our Photographic Heritage

PhotoWings: Do you get a sense that there are valuable photographic works at risk of being lost to the world forever?

Malcolm Daniel: Sure. There are many things that aren't recognized as having value and get discarded, and that's part of what causes rarity. But there are people that address this issue. There's The Judith Rothschild Foundation, which gives grants in support of preserving, acquiring, classifying, and exhibiting the work of recently deceased photographers who never enjoyed the kind of recognition that they should have during their lifetime. So for instance, sometimes they'll make a grant to an estate so that an artist's archive can be preserved and things can be properly housed and somebody can classify them and organize them and make sure that they're not discarded. It still has to be work of quality. Not everything is worth saving. Often people call up here - and call up probably every museum - and say, "My grandfather was a photographer and I have 4,000 slides that he took. Would you be interested?"

I'm not sure there is a home for everything. I think that sometimes a collection [of personal photos] is wonderfully valuable to someone like a local historical society. It's not all great art, and yet it can still have meaning. It can tell the history, through one family's eyes, of a town, for instance. And so sometimes, instead of being thrown out or put in the basement, it's really invaluable to a local historical society.

I'm not sure there is a home for everything. I think that sometimes a collection like that is wonderfully valuable to someone like a local historical society. It's not all great art, and yet it can still have meaning. It can tell the history, through one family's eyes, of a town, for instance. And so sometimes, instead of being thrown out or put in the basement, it's really invaluable to a local historical society.

But it's a real undertaking. It was one thing for us to acquire Walker Evans' negatives and to see to the restoration of those curlings, those celluloid nitrate negatives. That's Walker Evans. You know, it's a different thing if it's John Doe. A local historical society with very limited resources, how can they take 4,000 color slides from somebody? How do they ever know what those are? How do they classify them? How do they preserve them? It's a huge responsibility, unfortunately.

And then I think there are times when the truth of the matter is photography is so ubiquitous. The billions upon billions of photographs that have been made, most of them aren't worth... I mean, I hate to say that, but we can't preserve everything. We have to make value judgments.

And we can't always be certain that the value judgments that we make are [right]. And so I think things do get lost. But not every photograph can be preserved, so we as professionals—and everybody else out there who cares—tries to make those judgments about which things are the most revealing about history, about expression, about lives. Sometimes the only value of something is within the family, and they should be preserved by the family. So keep it, pass it on to one's children and grandchildren, and maybe it never goes any further. But if it enriches and gives meaning to family history, that's great.

We can't preserve everything. We have to make value judgments. And we can't always be certain that the value judgments that we make are [right]. And so I think things do get lost.

PhotoWings: Photographers tend to be good storytellers and a lot of them have been at the forefront of history. Have you been involved much with the oral histories?

Malcolm Daniel: I think there's a value, but I haven't been involved. I think part of that is simply that my deepest interests are in the 19thcentury. I could go back and do an oral history with Édouard Baldus or Roger Fenton or Edgar Degas. I would jump at the chance, but it's not an option for me.

PhotoWings: You've known a lot of photographers and photographers' stories. Is there a common characteristic that you've noticed among the ones who have become well-known or had their work recognized?

Malcolm Daniel: Well, hopefully they're the ones who have done the most exciting, new, expressive work. I don't know that that's always the case, but one would hope so.

Moving into the Future: New Media and Enriching the Web Site

PhotoWings: What would the public be surprised to learn about your collection?

Malcolm Daniel: I think one of the things that the public will be surprised to learn about The Met is that we don't just collect all those little brown photographs that I love so much from the 19th century or from dead photographers. We do collect up to the very present moment. We have been displaying our contemporary holdings over the last five years or so downstairs outside the modern art wing.

We don't just collect all those little brown photographs that I love so much from the 19th century or from dead photographers. We do collect up to the very present moment.

And also that we are pushing the boundaries a little bit of what has traditionally been collected by the Photography department. We have started to collect judiciously, slowly, in a considered way video and new media. And so we want to have a show of video and new media from the collection that will include works by David Hammons, Ann Hamilton, Lutz Backer, Omer Fast, Maria Marshall, Wolfgang Staehle, Jim Campbell, Darren Almond, and I think people will be surprised to see that at The Met.

We've chosen to collect those works which seem to be a natural outgrowth out of photography, so the same kinds of aesthetics and ideas and concerns that interest us in still photography are what we gravitate towards in video and new media. We have not collected, for instance, those things which are more narrative and cinematic like Matthew Barney. These tend to be things that one can enter, experience, and exit from on one's own time. You don't have to sit down and watch for an hour and a half, or even for nine minutes. You can come up to it, experience it, move away from it. They tend to be non-narrative and they have aesthetic or intellectual connections to photography.

We have many pages of information about photography [and photographic images] and other reproductions on The Met's Web site, within its timeline of art history. That's become a great resource for art history teachers.

We also have many pages of information about photography [and photographic images] and other reproductions on The Met's Website, within its Timeline of Art History. That's become a great resource for art history teachers.

We are working towards putting our whole collection on the Web. We should have all of our collection database records available to the public on The Met's Web site, with reproductions of those images which have been photographed, which is an ongoing project. And when we don't have permission, we'll just put up the collection record.

PhotoWings: So people will be able to purchase copies of these?

Malcolm Daniel: Eventually there will be a way to order prints. This will be really just for study - to know what we have here, to plan a visit for a study room.

I think one of the most important aspects of this will be that we'll get the Walker Evans archive on the Web. This is something that Jeff Rosenheim, Doug Eklund, and Mia Fineman - all of whom are still on staff - and a host of volunteers and interns have spent a dozen years cataloging. And it's an amazing trove of information about an artist who is central to 20th century art in America.

The same kinds of aesthetics and ideas and concerns that interest us in still photography are what we gravitate towards in video and new media.

At the moment, you have to make an appointment in our study room one of two mornings per week and sit at one computer terminal in order to know what we have. When we go live online, people will be able to look through all of Evans' photographs, the correspondence, the drafts of his writings, the work that he collected by other people. And they'll be able to conduct really thoughtful research on Evans just sitting at their own terminal.

PhotoWings: That's very exciting. Well thank you very much. Is there anything you would like to add?

Malcolm Daniel: Come visit. You know, I sort of feel bad ending on a discussion of sitting at your own terminal and seeing the things on the computer screen, because there is no experience like standing in front of the real thing. I wish we had more things on view at any given moment, but we do have photographs on view always and they change every few months. And we do also allow researchers to come in and work in our study room and to look at other things that are not on view in any given moment.

PhotoWings: Do you have to be a researcher to go to the study room?

Malcolm Daniel: No, but you have to know what it is that you want to see. We have limited space, so we can only take a few people at a time and only a few mornings a week. So we give priority to people who are bringing in a class and want to teach with actual works of art, or curators. But someone who has always loved the work of an artist that's represented in our collection can make an appointment.

We are working towards putting our whole collection on The Met's Web site, with reproductions of those images which have been photographed. I think one of the most important aspects of this will be that we'll get the Walker Evans archive on the Web. And it's an amazing trove of information about an artist who is central to 20th century art in America.

The Stieglitz Society Auxiliary at The Met

PhotoWings: And you also have an auxiliary, I believe.

Malcolm Daniel: We do. We have a Friends group called [The Alfred] Stieglitz Society, since Stieglitz played such a founding role in our history. It's now eight years old. We have about 55 members, either individuals or member couples. We have events more or less monthly during the school year which include lectures by artists, visits to studios, visits to private collections, seminars taught by the curators using the collection here, conservators showing what they're working on. There's a big annual dinner at which we curators present works of art for acquisition, and then there's a vote on how they wish their dues money to be spent. We've bought some great photographs over the years, thanks to The Stieglitz Society.

PhotoWings: Is there a percentage of dues that goes towards acquisition?

Malcolm Daniel: Except for [the costs of] running the program itself, which is relatively minimal, the money goes towards acquisitions. And it's been a great success and I think the people who are involved in it are very excited about it and are quite faithful to it. And we have now a range of age and interest and collecting experience. We started a new lower dues level for members under 40, and it's a great group of people actually.

PhotoWings: Are you noticing that younger people have a big interest in photography?

Malcolm Daniel: Well I think photography is an area young people collect, in part, because it is still relatively affordable and, in part, because it's a medium which young people are linked to. It's part of our modern world. So I think that was part of our motivation for making the Friends group more accessible to collectors.