Victor Blue: Pictures and Words

Photojournalist Victor J Blue loves to read. “I find it sustains me,” he says of the narrative nonfiction published by magazines like The New Yorker and Harper’s, “I think I probably went to them initially for the photography, and then stayed for the writing. I still read them every week, because the narrative nonfiction writers that are producing work for those magazines are such a strong influence on my photographic work.”

“We want to aspire to write at a level as strong as our pictures,” he says.

Though writing might not be the most obvious place to look for photographic inspiration, something is definitely clicking for Victor. To date his work has appeared in a wide variety of major media outlets, from The New York Times to The History Channel. In 2008 he was awarded a first place award in the NPPA Best of Photojournalism contest, and was a member of the team that won the Fairbanks Award for Public Service Reporting from the Associated Press News Executives Council for their project The War All Around Us. In 2010, 2011, and 2012 his work was honored or awarded at the Pictures of the Year International Competition, first for his coverage of the ongoing conflict in Afghanistan (2010, 2011), and then for Parlay, the project on his Grandfather (2011, 2012). He has shown photographs in exhibitions at the Powerhouse Gallery in New York City, the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis, and the Yerba Buena Center for the Arts in San Francisco. His work has won grant support from the NPPA and Ohio University.

He has photographed in Central America since 2002, concentrating on social conflict in Guatemala, and has photographed stories and completed assignments in Afghanistan, Syria, Mexico, El Salvador, Honduras, and India, and has documented news stories and social issues across the United States. He worked as a staff photographer at The Record in Stockton CA, and holds a Masters Degree in Visual Communication from Ohio University.

PhotoWings sat down with Victor at the 2014 Foundry Photojournalism Workshop (where he was an instructor) to talk about his photographic philosophy, his career as an international photojournalist, and, of course, all that writing.

How did you first come to photography and photojournalism?

I began photographing relatively late in life. When I finished college, I started years of running around with friends and going on road trips and having adventures. I had a small point and shoot camera that I carried with me all the time — a very cheap one. After my first trip to Europe with my brother and best friend, I got back and was disappointed in the photographs. I felt like they were of low quality and they didn't feel the way I remembered the trip. They didn't reflect my experience. So I convinced my mom to buy me a basic manual 35mm camera with a 50mm lens. I started using that to take photographs of my friends, and my life, and my family, and our adventures. I did that for years — for years and years — and then eventually came to a place in life where I was interested in engaging with the places I was traveling to in a way that was a little deeper, a little more fundamental. Around that time, I decided to become more serious about photography. Not too long after that, I discovered what documentary photography was. I had never thought of it. At the time, I didn't really read newspapers or magazines. I didn't know anything about documentary photography. But when I figured out what it was, I realized pretty quick that I was already photographing in that mode — a candid reportage type approach — to photograph my friends and family. I didn't like to set people up, I didn't like to make whimsical pictures, I didn't like to make portrait's that much. I liked to sit back and let things happen and try and make a picture. When I realized that there was a whole world of people who photographed like that — who photographed events, issues, themes, movements in the world, and did it with that approach — it seemed natural for me to pursue it. Not that it was easy. I wasn’t very good at it.

Do you ever go back and look at your early work or your family photos for inspiration? Do you see any connection between your documentary work and family photos?

I have a large family of friends that I've hung onto for, at this point, 30 years, and we're all still very close. And the funny part is how often photographs that I've taken over the years I see over and over again on their walls, on their Instagram feeds, in albums, as bookmarks. I'll come across them all the time. And at this point they've all been passed around so many times nobody says that they're Vic's photos, everybody's forgotten. But for years I've made these pictures and passed them out to friends. And now they're a part of our shared history. It's not too often these days that I sit down with folks and go through the pictures, but of course I'm a consumer of imagery and I love to go through it. And I've spent a lot of time the last couple of years on my granddad's farm pouring through his images. I mean literally thousands of old images.

I generally find people's family album photos to be much more powerful than my documentary images. I think the similarity is the desire to hang on to memory, that time is constantly passing, that the clock is constantly ticking, every moment that passes we miss. The camera gives us an opportunity to freeze and hang on to some of them. The job for documentary photographer, or somebody who aspires to make social documentary photography, or photojournalism, is to edit the world, and decide which of those moments are the most important to hang on to, and then hang on to them in a way that's dynamic and interesting and shows it to us in a way that we didn't just remember seconds before it passed.

I'm always surprised at some of the pictures that still seem to make the edit that I made when I was very green. I'm not sure how I pulled it off. A lot of them happy accidents. For some reason I had a moment of clarity that helped me do something that I can't seem to do that often now. I hope that my work has grown into a body that has a certain style and a certain point of view and a certain feel to it, but I don't know if my old pictures influence me that much. I try not to let them. I try to be making new pictures. But your pictures are a product of everything you bring with you. My pictures are a product of my background. My pictures are a product of the place I grew up. They're a product of my family. They're a product of my socio-economic background and my level of education. All those things. You bring all these things to the table, but the important thing is to make those strengths instead of let them be limitations.

"...your pictures are a product of everything you bring with you.

My pictures are a product of my background. My pictures are a product of the place I grew up. They're a product of my family.

They're a product of my socio-economic background, and my level of education. All those things. You bring all these things to the table, but the important thing is to make those strengths instead of let them be limitations."

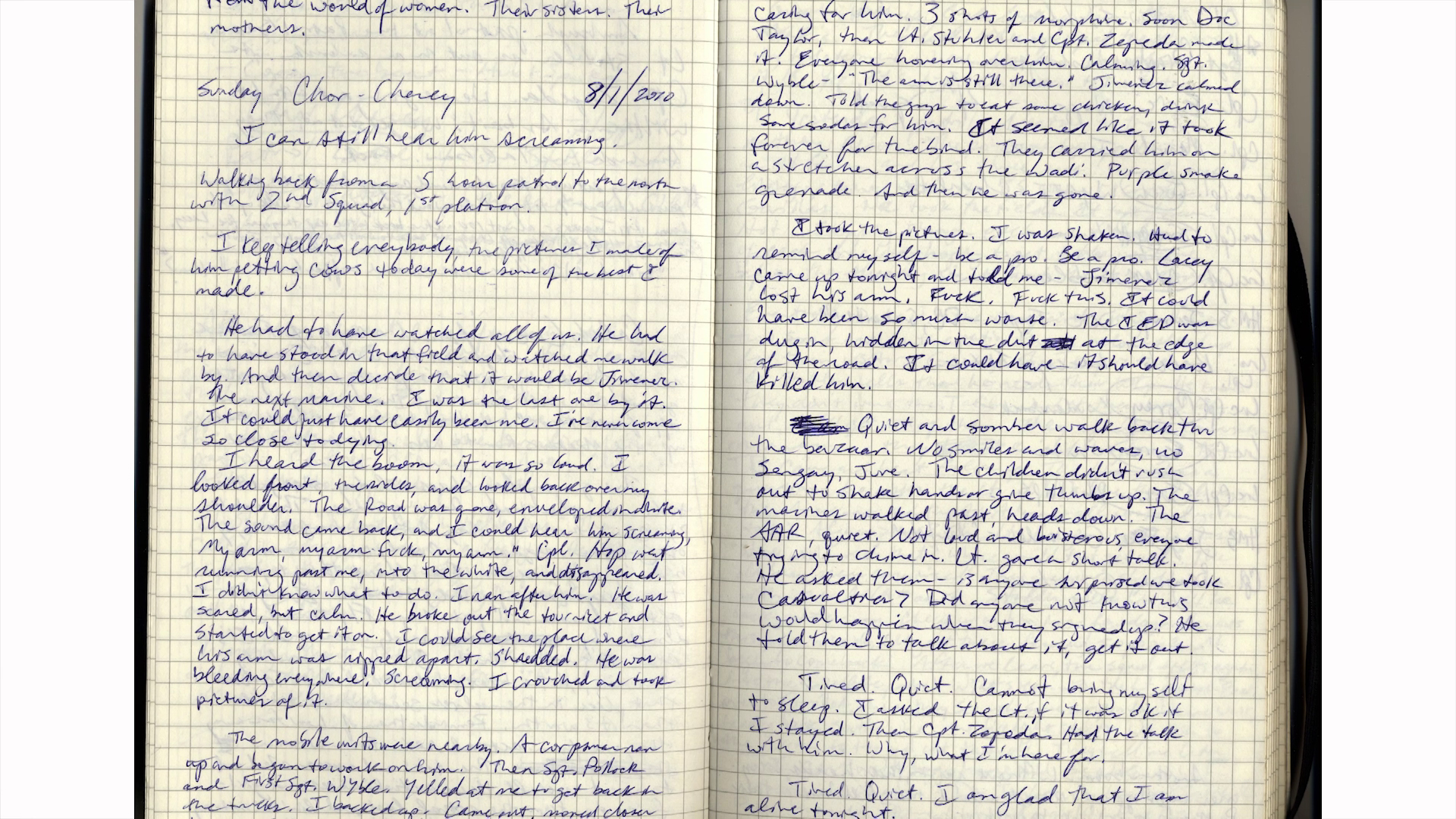

It took a long time for me to figure out what I was doing and start to make the pictures that I knew I wanted to make. I'm very influenced by narrative nonfiction writing, long form journalism, newspaper writing, contemporary fiction. I read widely and I read pretty deeply. It’s a huge influence for my work, and I also try as hard as I can to incorporate my own writing into my documentary photography practice so that it focuses and sharpens my thinking, and, I'd like to think, makes my stories deeper and have a different perspective than your average set of documentary photographs. I try to photograph my story as I go along, and writing personal dispatches connects me with the people in my life that I'm away from and it helps me organize and understand my experience. I've written thousands of words over the years for them [which has] dramatically focused my journalism and helped me understand my personal reasons for pursuing it.

How did you first become interested in writing?

When I was at Ohio University I spent a significant amount of time studying writing. There was a big push — there's still a big push — in the industry towards multimedia, towards photographers learning to gather audio and video, and it's an important push. It's an important innovation for our new life on the web and the life of our stories on the web. And I do all those things. I shoot short documentary and I love to gather audio; I think it's an important component of my journalism. But I decided to focus on what I find to be a more fundamental version of multimedia — I focused on learning to be a better writer. I had the pleasure to study with the dean of the Graduate School of Journalism at Ohio University, Michael Sweeney. He turned me on to great writing — great dispatch writing — and also gave me a toolbox to use to improve my writing dramatically.

Photographs don't exist in an ether. They don't exist out on their own, especially not documentary photographs, especially not photographs that try to tell a story about the world. They want to tell a story that's based in fact. They don't exist without themselves. No photograph exists without at least a caption. Clear, effective captions that don't repeat action. There's so much opportunity, or so much need, for writing that goes along with photographs to provide context, to help readers connect with the pictures, and the more of that work that we photographers do, the better. No one can do it better than us. No one else was there; no one else has a budget to pay for someone else to do this writing. We have to do it, and we might as well do it well. We want to aspire to write at a level as strong as our pictures. I've learned over the last few years to write news pieces because I produced photographs, photo stories, that weren't going to find a home if they didn't have a news piece to go along with them. So I have adopted that role.

"We want to aspire to write at a level as strong as our pictures."

I've learned that as photographers, especially in this current context, we spend way too much time worrying about the aesthetics of our pictures rather than worrying about what we point our cameras at. I think we forget to be great observers, great noticers. That's my thing. I think great photography is great noticing. I'm always intrigued by the most simple photograph. If it depicts something interesting that I hadn't seen before, that's different from the world that I move in now, I'm always so struck by it. I think, “God I do not do that enough.”

Students gather around Victor Blue as he discusses course material at Foundry Photojournalism Workshop. Image courtesy Suzie Katz

How has been the experience teaching the students here at the Foundry Photojournalism Workshop?

I like teaching. I like people learning, and if I can I like having a part in that. I want everybody to be really good. You know, I got into this sideways, and it’s probably unhealthy, but I carry a little bit of a chip on my shoulder about not finding mentors early on who could kind of point me in the right direction. But one of the things that’s come out of that is I really enjoy helping point people in the right direction. I enjoy telling people stuff that I didn’t know. I enjoy helping people figure it out faster than it took me to figure it out. So in that respect I like teaching.

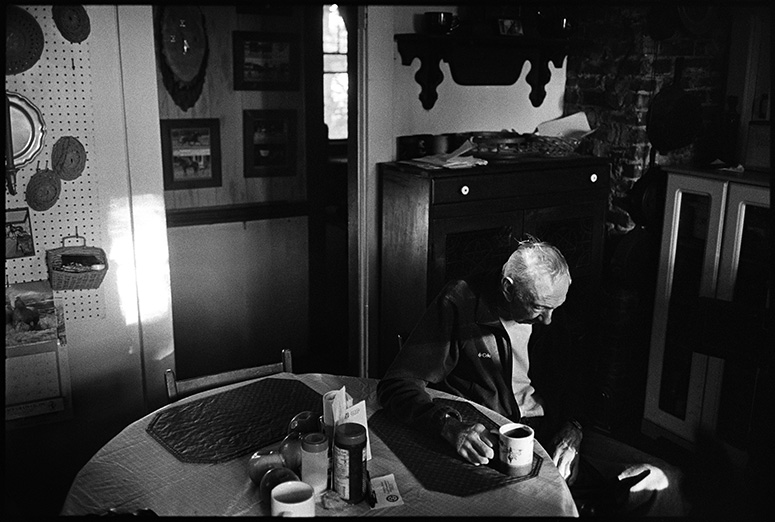

Mr. Taylor in his home. Image courtesy Victor J. Blue.

A project you’ve gained a lot of critical accolades for is Parlay, which focuses on your grandfather. Can you talk a bit about that work?

I take a very similar photographic approach in almost all my projects. I don't photograph my grandfather any different than I do when I'm working in Afghanistan. I try to take the same approach. I try to take a personal approach. I try to take a very human and sensitive approach. The visual dynamic might change, and I might be trying to depict a different story or a different theme or a different feeling, but at the end of the day I think I photograph very similarly in Indiana or in Kabul or in Novak, or in any of places that I work. I want those same photographic values to be expressed in a variety of contexts. Someone said one time, “photograph a riot like a wedding and photograph a wedding like a riot.” I try to take a real similar approach. I want people to have the same emotional connection with troops on patrol in Afghanistan as they do with my grandfather making his breakfast.

But of course the process was different. I didn't have to do as much research and I didn't have to fight so hard for access and I didn't have to jump through so many hoops talking to NATO and ISAF to get access. I just drove across the state and spent some time [with my grandfather]. It's weird how similar the actual shooting is though, that's always strange. It's not a natural thing for anyone sit and be observed with the camera. My grandfather's no different. He's just as curious and feels just as awkward as a first sergeant does on a combat patrol. It’s a weird thing to have the camera put in your face and have somebody intently watching your every move, and he reacts very similarly to anybody else who is put in that position. But of course I'm his grandson, he sort of has to let me hang around, and I tend to do a lot of work around his farm, so he's kind of cool with that. And at the end of the day he understands what I'm doing. We sit around and talk about Afghanistan. We sit around and talk about Guatemala. We sit around and talk about DC and politics. He's seen the work, he knows what's happening. It doesn't make him any more amenable to being photographed that's for sure, but he understands.

Are there ways to ease that tension between photographer and subject?

Yeah for sure. Obviously there are experiential things you do. I look everyone in the eye. I try and shake as many hands as possible. I try to be very quiet. I'm kind of tall, so I try to make my profile match as closely as possible to people I'm with. I don't stand out, I don't intimidate. I'm reading body language. I'm listening. I try to be genuinely curious and genuinely interested in people. And I try to let them know that. So I just try to be as open with folks, and as clear with folks as I can. I'm big on the DTR, the “Define The Relationship” talk. You explain what your role is, what you're doing there, why you're doing it, why they should understand what you're doing. And I've had that conversation with almost everybody I've ever photographed in any kind of deep way. It is not always fun, but it’s always useful.

It's not a natural situation to be in with someone else. It's strange and it's not something I've ever gotten over. I think some people probably do. But for me it's difficult and it's always awkward and every day that I go out to photograph I face the same anxiety about doing that awkward thing. But at the same time I know the value of it, and I know how important it is, and I know that what's going to come out of it is going to be worth it for them, for me, and for the people that are going to see the picture, so I just kind of fight through it. I'm always hoping one of these days I'm going to wake up and it's not going to bother me, but it seems to still bother me, every day.

The other thing that always happens is people always get used to it, people always kind of forget you're there, and people always appreciate your honesty and your transparency. And people recognize it and they value it. What I always tell people at the end of my DTR, I always say, “I'm not here to try to make you feel cool, I'm not here to make you look great, I'm not here to make you look beautiful, I'm here to show you how you are. I'm here to hold up a mirror. You might not like the way you look in the photographs, but you'll never look at one of the photographs, or read anything I write, and say that didn't happen. That's the tradeoff I make: that you'll be able to believe in the veracity of what I produce. You might not like the way you look all the time, but I don't like the way I look in any photographs to be honest with you. But I'm glad they exist."

"I try to be genuinely curious and genuinely interested in people.

And I try to let them know that."

When you’re in the field, how do you assess the safety of a situation? What is going through your mind?

I mean, it's so hard to say because it's so specific to the time and place. But I'm gauging risk. I'm wondering is it safe to jump in this vehicle with these guys? What do I anticipate is going to happen? What is the normal profile of violence in this area? Who do I think is exercising it? How well protected am I by these people? What risk am I taking on by being with them? What risk am I taking on by being away from them? It's experiential; it's things you pick up as you go. It's totally experimental. You have to be smart enough to realize risk in one country or one context or one town in one country isn't the same as risk in another one.

The more experience you have, hopefully, the easier it is to gauge that risk and to know when to go, when not to go, when to do something, when not to do something. You're constantly weighing, balancing. It's like a math problem that you're constantly working out in your head. And, to be clear, I have the advantage of being a middle class, white, American. That gives me a level of entre around the world that unfairly isn't available to everyone else. I try to use that unfairness as an advantage in that I'm able to move in many parts of the world and hopefully make pictures and tell stories there that other folks can't. I don't feel guilty about that unfair advantage but I'm constantly cognizant of it, and I try to use it as a tool, I try to make it a positive instead of a negative for the world. So it's not very often that I'm at nearly as grave risk as the people I'm photographing. I get to go home, back to North Carolina or back to New York, and I see my friends and family who don't live under political repression, who don't live in a marginalized part of their society. Who don't live under the constant pressure of scarce resources. I'm fortunate that way. I take that role seriously.

How do you cope with the sorts of things you see in conflict situations?

The effect of documenting and witnessing violence and difficult situations does take its toll. And I think it’s different for different people. I have my ways of coping with it. I write about it. That’s one thing that helps. I go back and listen to audio recorded. I’ve certain trusted folks that I talk to about it. And I have my own kind of ways of processing it. I tend to process these things a little bit down the line. I have my crying jags in the dark to help me get it out, help me understand it, help me process it, you know. I’m not in any way immune to it. But I’ve developed my own ways of, of coping with it. Of dealing with it. And honestly it’s always so much worse to the people we photograph. I can’t compare my two months in Afghanistan to a nine month Marine deployment. Those two things are really distinct; there is a huge difference. So while I do think it affects journalists and it needs to be coped with in a healthy way, I tend to like to focus more on the folks who are the players in those situations, and how it focuses on them.

It’s interesting that we’re talking with you today in Guatemala because this is actually the first country to visited as a photojournalist, correct?

I initially came to Guatemala to learn Spanish in 2001, and it happened that that was around the same time I became serious about photography and discovered documentary photography. I decided to come to Guatemala and try and shoot a project. I didn't know how, but I decided to make a go of it. I came and I brought a bunch of film, and a couple of cameras, and did what I thought photographers do: made a set of pictures. Some of them I still value and still make it into my edits in my work. I had traveled to quite a few countries at that point as a traveler — as a tourist. I had been interested in these places, and interested in looking for something in these places and I'm not sure what it was, but I had never been to a place that wore itself on its sleeve like Guatemala does. I'd never seen a place where you could see right in front of you, every day, so many expressions of its difficult history. I was drawn to that and I was drawn to trying to understand it. And trying to make pictures of it. So that was much more complicated than I initially thought it was going to be, and I keep coming back until I've said what I want to say I think.

I've shot human rights violations in Guatemala for years and documented the effort to not only reclaim historical memory lost in those violations, but also to demand justice for the victims of those violations. And in Guatemala the violations rose to the level of genocide. In other places they don't, they're human rights violations that don't fit this political definition of genocide. I'm not sure that I feel like one is necessarily more important than the other, I believe a violation of anyone's human rights is a tragedy and a travesty. But it's true that genocide, as a historic phenomenon, is hard to wrap our minds around, but it is important to try. And I value my time here trying to understand the genocide in Guatemala and trying to say something about it, trying to make sure that it's not forgotten. And do our best to help and not happen again. So I find myself here yet again.

Members of the Mara 18, El Hoyon prison. Image courtesy Victor J. Blue

It’s become a really complicated story. How do you deal with the really complicated stories like the one your telling about Guatemala?

I think that it's important for photographers to be focused and clear in the story they want to tell. The smart thing to do for me is to break really big complicated stories up into smaller pieces. Every time I make a trip to Guatemala, I have an idea for a shorter-term story that I want to do that fits into this larger project. Each time I come I have another idea, or another focus.

I started photographing here in 2002, and the project's gone through quite a few title changes. Right now I call it The Darkness After the Dawn, or Darkness After Dawn, because I came to Guatemala in 2002, which was six years after the signing of the Peace Accords when the wounds of the warriors were still kind of open and only beginning to scarify. And the signing of the Peace Accords was the idea of a new beginning for Guatemala. But, as Guatemalans have seen, it's actually been a slide backwards. So I'm trying to say something about this increasing darkness that came after this moment of real optimism.

I came in 2002 and spent time with ex-guerilla combatants growing coffee, because I wanted to see what their life was like after the war. And I came back in 2003 to cover a political campaign of the former dictator Efrain Rios Montt. I also became interested in land issues, and issues of land conflicts. And then, I was introduced to the process of exhumation and reclamation of historical memory by the victims of the war through the work of the Guatemalan Friends of Anthropologists. So I started what's been a long collaboration with them, photographing their work for years, starting in 2003. I came here for one reason in 2005, and quickly realized that the repression of the gangs, the wave of violence known as the social cleansing, was the most important story at the time; sometimes you're here and a story presents itself. In 2007 the violence had ebbed, so I came back and I concentrated on an area of Guatemala that's been the focus of large-scale immigration in the United States and I photographed there and in California, where I was living, to try and get both sides of that. In 2011, I came back to photograph the ascendance of Otto Perez Molina, the current president, who was the former military intelligence chief in the war years, and the irony of former military leaders responsible for some of the worst years of the repression becoming the president of Guatemala again. And then in 2013 I came back to document the opening of the Genocide trial against Rios Montt. So every time I come it's like another chapter that I'm trying to work on and I'm trying to add to this broader project.

"I’ve created a body of work. I’ve created evidence. Not just evidence,

I’ve created a document to help people understand..."

Hearing you talk about Guatemala, it seems you have a deep knowledge and care about the place. Do you hope your photojournalism will ripple through the political world to help change these sorts of situations?

One of the main ambitions that I have for my work in Afghanistan — which concentrates on the implementation of the counter insurgency doctrine in Afghanistan with Obama’s two surges into that country — is I want to have a place in the policy debate. I read widely and deeply about military policy in Afghanistan. I spent years coming to Guatemala photographing the effects of counter insurgency as it was implemented here, and when I first started to hear military leaders are going to implement a counter insurgency program in Iraq and in Afghanistan, it made the hair on the back of my neck stand up. I’ve seen the mass graves. I’ve seen the human rights violations. I’ve seen the villages burned to the ground. I thought, “Well, that doesn’t sound like a good idea.” But then, as I read about it, I realized that there had been a serious reassessment of the doctrine. And the way they were going to implement it now sounded like a good idea. But I wanted to go see if it was or wasn’t. And there’s a raging policy debate around the counter terrorism versus counter insurgency approach. Of course that debate’s been a little bit put to bed as we wind down these two theaters of our global war on terror, but I want a place in that debate. And as I read, I recognize what is missing from the debate is found in my photographs. I recognize how much there is to learn about counter insurgency in Afghanistan from looking at the pictures. I’ve created a body of work. I’ve created evidence. Not just evidence, I’ve created a document to help people understand what it meant to implement this doctrine in Afghanistan and what it means for conflicts that we will inevitably be involved in in the future.

"I love that the world consistently surprises me. Every time I show up and I think I know how this is going to go down, every time I show up and I think I know who these people are and what they’re going to be about, they have no shortage of surprises in store for you. It never gets old."

Do you think that becoming a photojournalist has changed your perspective on the world?

Absolutely. It changes the way I see the world over and over again. One of the reasons I keep doing it is because I love that the world consistently surprises me. Every time I show up and I think I know how this is going to go down, every time I show up and I think I know who these people are and what they’re going to be about, they have no shortage of surprises in store for you. It never gets old. And so yeah, it’s changed the way I look at the world. I love being a journalist. I try not to do it too much, because it’s untoward, but it’s amazing to sit around a dinner table and people talk about issues or events in the news that they haven’t had the opportunity to be first hand witnesses to and understand how much more profoundly you understand those things that they do, because you go see them first hand.

But I think one of my favorite things about having spent 11 years as a working journalist is that I have been disabused of any ideology that I once harbored. It constantly surprises me that out in the world, our political ideologies, whatever they are, left, right or center, have a tough time fitting with the complications of the real world when you get out into it. It's hard to make those square pegs fit into round holes. I feel fortunate to have let go of a lot of the ideology that I might have at one time held onto. A buddy of mine complained about it to me recently. He kind of shouted at me, “You know, Vic, you've lost all your ideology.” And I was like, “Yeah, I've lost all my ideology, but I've held on to my idealism, which I think is far more important.”

It’s a privilege. I feel it all the time. You’re spending time with people and you get to watch something happen right in front of you. Something unexpected and you just think, “Wow I can’t believe that I got to be here for this.” I have a set of pictures of a kid swinging a stick at a Piñata at his birthday party. I spent a lot of time with that family, and that birthday party went all day and all night. It was genius, it was totally fun, it was great. And I remember at the end of the night being kind of worn out and definitely feeling from where I come from to where I ended up, what a lucky road.