Mark Tuschman – Faces of Courage

Mark Tuschman’s 30-year career in photography has taken him across the globe and back. In his travels and work, he has documented the struggle to make women's lives better around the world. Tuschman wants to tell the story of how they are denied basic human rights — like health care, education, and even control of their own lives — as well as the work done to address these issues. PhotoWings recently spoke with Mark via email on his photography, his advocacy and more.

You were once pursuing a PhD at UC Berkeley for Physiology but eventually became a photographer. Can you tell us the story of that shift? Did your engineering/science background influence your photography? Has photography changed the way you see the world?

I was studying neurophysiology of vision in the biomedical engineering/computer science department. My research was not going well, and a fellow student was returning to his home in India, stopping along the way in Hong Kong. He asked me if I wanted anything from Hong Kong, so I gave him $150 and asked him to buy me a camera. Another friend in the department had a functioning darkroom; I bought some Ansel Adams books and quickly got addicted. It felt so good to see some results in the darkroom compared to endless, frustrating hours in the lab without any results or satisfaction.

It still took about 10 more years before I turned professional. I lived in Denmark after grad school, and I started photographing more. When I got back to the States, I landed a job at Stanford Medical Center where I was in charge of a computer system creating a relational database to help evaluate treatments. I was doing photography during this time and working on another project, “Where We Stand,” interviewing and photographing older people with disabilities who excelled within their physical limitations.

My goal was to be an art photographer and have exhibits and make books. I did in fact have some exhibits in San Francisco, and SFMOMA bought some of my work, but I realized I would starve following this path. When my son was born in 1979, I had to make a big decision whether to continue in computer science or become a commercial photographer. I probably would have pursued more of a National Geographic route, but I realized that I did not want to be away endless months on assignment and miss my son growing up, and so I became a corporate photographer.

I am not sure if my engineering/science background influenced my photography. Engineering used a part of my brain that did not give me much satisfaction. Having this background and skill set likely made it easier to learn the technical aspects of photography. Perhaps ironically, my original work has come full circle since the advent of digital photography. I spend a lot of time on the computer with my images, but I find it much more satisfying— quite different than programming in machine code.

Photography has changed the way I see the world, most definitely. I am a curious person, and I have used photography to try to understand why the world is the way it is. I have to say after all my travels and experience, the inequalities are quite incomprehensible. I live in an extremely affluent area, and when I am photographing people in some of the worst slums on the planet, the injustices strike me to the core. I try to show in my work some of the gross social injustices that need attention to be corrected.

Who are some photographers you admire? Can you tell us why?

I am a great admirer of Sebastião Salgado. He is definitely a hero of mine. His tenacity and commitment is so admirable. I have a quote of his on my webpage: “If you take a picture of a human that does not make him noble, there is no reason to take this picture. That is my way of seeing things.” His work has so much compassion in it, and I love his sense of light and composition. I also am a great admirer of Steve McCurry; his use of color and his portrait work is exceptional. People think it may be easy making a good portrait, but it is not; in reality, there are very few portraits that make it past the editing process.

I am basically a self-taught photographer and studied the work of the great masters like Eugene Smith and [Henri] Cartier-Bresson. As far as portrait photographers, Irving Penn greatly influenced me — especially his book, Worlds in A Small Room. His sensitivity to light has become part of my way of seeing. And Diane Arbus portraits were arresting— they caught a moment that revealed something deep and not superficial.

I also am a great fan of Gregory Heisler— I think he is a genius. I took a course with him back in Maine around 30 years ago and also one with Jay Maisel. They were both fantastic teachers. I also admire Albert Watson’s photography.

What are your other, non-photographic, influences?

My wife is an artist, and I learned a lot from her. I never had any formal training in photography or art— I was basically trained as a scientist. She made me aware of composition, texture and design. We always went to museums, and when I teach workshops, I always tell my students to study some of the old master paintings— Rembrandt and Vermeer particularly. Everything I can teach about photography, I can teach from studying the work of these masters— the use of light, gesture, composition, color etc.

You’ve photographed in many locations around the world -- how did you come to work in these locations and establish relationships with your subjects? How do you earn trust?

To do the work I do, I frequently collaborate with an NGO [nongovernmental organization] on the ground. I just cannot show up in a village and start photographing. The NGOs help create bridges to people that I would not ordinarily have access to meet, and with that also comes a sense of trust. The NGOs bring me into communities or clinics or other situations where they have empowered the people I will be photographing, and I communicate that intention as well:

I am here to help tell your story, one that needs to be told; your story is important and hopefully by sharing it, it will help people who also may be in your situation. I communicate trust by not rushing the process. I try to take my time with my subjects, and they see I am not just taking a snapshot but doing something special.

Nazia is telling her story to a women’s support group. Her husband tried to murder her twice, once by pushing her off a motorcycle, and once by poison. He was not satisfied with his dowry gift of a motorcycle; he wanted a new car. Nazia broke into tears shortly after I photographed her (ActionIndia/Global Fund for Women). (Copyright Mark Tuschman)

When and how did you first start working with organizations that address humanitarian issues? How would someone break into this today? Is it different now?

Back in early 2001, I had been a follower of Nick Kristof’s column in the New York Times; as you know, he writes quite frequently on the terrible treatment of women and girls around the world and also of the work being done to empower them. I had a friend who was on the board of the Global Fund for Women, and she arranged for me to go to Asia for three weeks and document some of their grantees. I produced a printed piece, and this is what I wrote in the introduction:

As I have grown older, I have become more motivated to use my photography to communicate in a more socially conscious way — in a way that would expose people to both the degree of human suffering that exist in today’s world and the courage and fortitude that people manifest to overcome it. It is my hope that my images will move viewers to respond not only with empathy, but with action.

I believe it is especially important for people in our society to understand other cultures and the enormous difficulties that people in other countries face daily in order to simply survive. The human condition is wrought with great uncertainty and suffering, and yet the human spirit and the hope for a better life can grow stronger in the face of adversity. The women I met showed me both the tender fragility and the profound fortitude that characterizes the paradox of life’s existence. It is only with compassion and the will to take action that we in this country, which has been blessed with freedom and great material wealth, can offer a sense of hope and justice by supporting the aspirations of these women.

One has to do this work out of passion. I get many emails from young students who want to do what I am doing, and I explain to them that I basically earned my living as a commercial photographer, and it enabled me to have some free time (much later in my career) so I could pursue some of my own personal interests.

I honestly do not know how one can make a living doing just work for NGOs; I have done much of my work for only expenses, and when I was reimbursed, it was only a small percentage of what I would get working commercially.

As I have mentioned, to do this work one has to be passionate about the issues and people you choose to document. The reward will not be financial; the reward is in the act of doing something you feel will help others, raise consciousness, bring about some action that will improve people and the environment in which they live.

I think it is important for any photographer to work on some personal project that they care deeply about.

I believe it is harder to break into this work now with the advent of digital technology. Everyone with an iPhone is now a photographer, and most NGOs will have their own people just go out and take some quick snapshots and feel that is all they need.

I explain that if they send me, they will get a library of really great images they can use, and the quality of the images they will be getting will be on a whole different level. When they see my work, they can see the difference. But, unfortunately, most NGOs put very, very limited resources into photography— I get the feeling it is one of their lowest priorities. If an NGO sends me out to do a job, I want them to make a profit from the images I bring back; I want them to use them in fundraising so it will make an impact.

I would advise young photographers who want to do international work, knowing all the financial limitations, to start off by working with some local philanthropic organizations in their own communities. Passion is the key— choose an organization whose work coincides with your deeply held beliefs and interests.

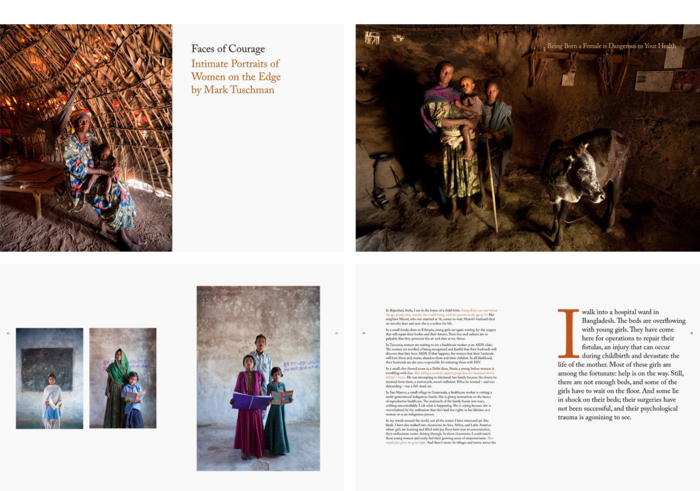

Your most recent project is Faces of Courage: Intimate Portraits of Women on the Edge. Can you tell us the story of its genesis and what your goals are for the project?

I have been working on the Faces of Courage project for over a decade. It has evolved slowly. A great deal of the work was done pro bono, and I had to continue doing commercial work to support myself and my family. I collaborated with NGOs and foundations willing to make arrangements for me to document their work. Doctors, nurses, teachers, aid workers, and NGO staff— these are the silent heroes who are working tirelessly to improve the lives of millions of women around the world. This book showcases the noble work they do.

I think Faces of Courage is very timely, as there is a growing movement in the United States and abroad that is hungry for real, substantive content on women’s human rights; people yearn to explore and understand more fully the facts and issues involved. I intend its message to be an effective communication tool, while shedding light on the heroic work of the small, grassroots organizations featured throughout. As the book’s images and stories show, the struggle of women to gain autonomy over their own lives is a battle of epic proportions. The selected photo essays heavily emphasize the positive impacts of family planning and girls’ education.

I have been asked more than once why, as a man, am I focused on the rights of women? The answer is simple: because they are a human-rights issue, not just a female issue. Millions of women face travails on a daily basis that are an outrage and totally unacceptable. It is my deep hope that this project will inspire more people to join in the effort to bring dignity and hope to the lives of marginalized girls and women everywhere. I hope to raise enough funds through my Kickstarter campaign to be able to donate books to schools and libraries to help create a new generation of activists.

In your Kickstarter, you write, “Faces of Courage is unique – no other photo-documentary has portrayed the full scope of this human drama as it unfolds around the world, including the efforts to help women move from tragedy and despair to hope and triumph.” What specifically makes your book different from others?

I am attaching a table of contents. I cover a very broad range of topics.

I start out by explaining why women are the poorest of the poor and why “being born a female is dangerous to your health,” a quote from Anne Firth Murray, founder of the Global Fund for Women.

The next section is on the ways women are “beaten down”— their lack of access to maternal health care, [child marriage], fistula, AIDS, teenage pregnancy. The largest chapter in this section is on physical violence against women.

The next section is on “Standing Back Up,” describing some programs on microfinance and agricultural empowerment. I continue by honoring healthcare workers and continue with family planning programs, including sex education for teenagers.

By far, the largest section in the book is on girl’s education and I conclude with a portfolio of young girls that illustrates the goals of the United Nations Populations Fund, “A world where every pregnancy is wanted, every childbirth is safe, and every young person’s potential is fulfilled.”

I also highlight a few exceptional teenagers who have benefitted greatly from the work of the NGOs.

What are the ethical considerations of creating a photography project such as Faces of Courage?

In photographing people, I always try to bring out their character with a sense of dignity. The more travels I have made have only further convinced me that it is only fate that determines where we are born. We have no control over who our parents are or if we live in a relatively wealthy society or one that suffers greatly for basic health and survival needs. Hence, I try to give my subjects the dignity they deserve as most people do the best they can under the circumstances presented by their cultures.

A young woman named Seni is shown here outside of Yogyakarta, Indonesia, with her family in the background. She was effectively held prisoner as a domestic servant in Saudi Arabia for three years without being able to contact her family (Rifka Annisa/ Global Fund for Women). (Copyright Mark Tuschman)

Can you elaborate more on ethics? How do you decide which photos to include and not include in your work? What is the experience like deciding whether to photograph someone who is in difficult situations — and how do you do it?

Even though people I photograph may be in very difficult and emotional situations, I try to edit my images so the subjects still retain their dignity. Sometimes I come across a situation that is so terrible, that I can hardly pick up my camera to photograph.

I took one photo of a young woman in Nicaragua in a clinic who was in agony after her uncle had kicked her very hard in her chest— he was drunk. It was hard for me to see this and it would be too hard for a person to view a photograph as well. If I want to communicate effectively, I cannot show images that are too difficult for people to see. Of course, there is a large range of what people can tolerate without being turned off. I just try to use my own sensibilities.

There are many ways to share photographs -- as prints, online, etc. How do you see the book format advancing the message and ideas of your work?

There are so many images on the internet that good work can easily get lost. The attention span of people when using the internet is incredibly short. A book has a more lasting impact. One can sit quietly and not be distracted by emails and instead leisurely read and view the images. I guess I am also of the generation that unless I see something in print, it is almost not real. As a matter of fact, I have to make a print to really evaluate a photograph— it is much different on a monitor. I think having a book available in schools would make a big difference. It is also a great fundraising tool for the NGOs I have documented.

Some may attribute the societal roles of women outside the West to different traditions or cultural values, which need to be respected — or at least tolerated — as an outsider. How do you address this kind of thinking?

Honestly, I don’t have much tolerance for this relativeness argument. When slavery was accepted, people were making the same argument. I believe in universal basic human rights and if one looks closely at the situation of women and girls in many cultures of the world, it is not unlike the conditions of slavery, which no one would argue is acceptable.

How did you choose which cultures to feature in your work? Are western women in your book?

The cultures I feature in my work are really determined by the NGOs and foundations I have worked for. It is where they have chosen to send me. I would have liked to document more in the Middle East but as a man, it would be very difficult to photograph the women— perhaps impossible.

I did some photography for a pharmaceutical company in the slums of Camden and Baltimore, both very frightening environments. I felt that I was in a different country, and in fact, it is a stark reminder of the gross inequalities that exist in our country. I am planning to do more work in this country, but it is not easy. I will give you an example:

After I did a library of images for Planned Parenthood Global, I tried unsuccessfully for over a year to do similar work here in the US. They were fearful of identifying people, the danger it might represent to their safety, all the HIPPA privacy requirements, etc. This is a good example of the sad state of women’s reproductive healthcare in our own country.

How would you teach others to use photography as an effective tool to encourage change?

I can only teach people what I know from my own experience. Everyone will have a different way of working. As I have said, I try to show people with dignity. When I am working abroad, I do not have lights except for a Speedlight, so I am always looking for good natural light situations. Certain light has a very emotional, almost spiritual quality to it— window light, particularly north window light, and I use that as much as possible. And then I look for backgrounds which help tell the story that I am trying to convey and then the work begins to try to capture the right sense of gesture and emotion. If I am doing a portrait, sometimes I can do it very quickly, but many times it takes some real work to find just the right angle, with just the right focal length, with just the right expression and gesture to make it memorable.

How can NGOs and other organizations effectively use photography?

There is a famous quote attributed to Stalin that the death of a million is only a statistic, but the death of an individual is a catastrophe. We as humans cannot personalize statistics, but we can certainly have empathy for individuals. I made my living as a commercial photographer doing many “testimonial” portraits of people, particularly for the healthcare and pharmaceutical industries. Advertisers spend enormous amounts of money casting just the right person and presenting them in the most empathetic way they can because they know it is effective.

I would tell NGOs to use the same approach: Highlight a person whose life has benefitted from their work; make it personal, and [the NGOs] will be successful in communicating their efforts to improve lives and make this a better world for us all.