Interview with A. D. Coleman

The critic, peering through a lens.

© 1995 by Nina Sederholm and Peter Guagenti. All rights reserved.

We talked to pioneering photo critic A.D. Coleman about his career, how he deals with criticism himself, how photography critics help popularize the art form—and where he says you’ll find soon-to-be-discovered photographers and the most cutting-edge images in the world.

The Evolution of Photography in the Late 20th Century

PhotoWings: You’ve been around for a long time. How have you seen the medium change in terms of the photography itself as well as the perception about photography and the collectors’ points of view?

A.D. Coleman: Well, the collecting base in photography really emerged starting in the early 1970s, I think, largely as a result of two things. First of all, the increasing price of material in the other arts, both contemporary and historical material, which made it difficult—especially for beginning collectors, or people on any kind of modest budget—to acquire work of any significance. But at that point, you could still acquire very important work by major figures in photography at prices in the two figures, or the low three figures.

So it was a very inviting medium for someone to enter who just wanted some art on the walls, some creative work on the walls, and some creative work of substance. Rather than spending $3,000 on a third-rate [Robert] Rauschenberg print of some kind, you could get 10 substantial [photographic] images for $3,000. This was, again, the late '60s through the early '70s. I think this was also fed by the photo-education system, especially in the U.S., which I really see as a germinal phenomenon in the photo scene as a whole.

And that system had been put into place from the 1950s into the early 1960s, I would say. That was really when we started to see the growth of the photo-education system, in the post-World War II period. More and more people were looking at photography at that point as a medium they might want to practice, or at least as a medium they might want to study.

And so, photo programs, on the higher-education level, burgeoned during that period. And the graduates of those programs, of course, became, in many cases, photographers, including many photographers we look at now as major figures in the field—who, one way or another, went through the photo-education system. Whereas in the generations prior to that, people had largely learned photography either on their own, or by apprenticeship with someone else or, on rare occasion, in some kind of school or workshop like the Clarence H. White School. But that act of getting an MFA degree in photography is really a phenomenon of the 1950s and 1960s. So major figures like Jerry Uelsmann, Bruce Davidson, Pete Turner—one could go on and on, Emmet Gowin, etc.—all came out of photo programs.

So they became, in a sense, aware—because they were educated often in the context of photo programs that were in art institutes or in college/university environments that overlapped with, or existed side-by-side with, programs in the other art media such as sculpture, painting, etc.—they became very aware, in the course of their studies, of these other media. As media for them to consider hybridizing with, in some cases. But also they became aware of the market in those media, and ways in which people prepared their work for the market in those media. And, as a result, I think they came out of their educational experience much more savvy about marketing themselves than previous generations of photographers had been.

Beyond that, although many of those people did, of course, become photographers, many of them decided—for whatever reason, including the fact that they may not have had the talent—that they were not going to pursue a career as photographers. But they loved the medium, and were going to want to do something in the medium, and they became curators, critics, historians, conservators, sometimes collectors.

Certainly they formed, for the first time, a knowledgeable collector base for the medium, which it had never had before. They and their [teachers] recovered all of the historic processes of photography that had mostly been forgotten or ignored or neglected—everything from the daguerreotype to platinum printing. So now we have wet-collodion printers and tintypists and cyanotypists , and so on. I think one of the notable things about this moment in the medium’s history is that all of the significant previous technological forms of photography are being practiced at the same time.

And one consequence of this, from the standpoint of collectors, is that there is a remarkable diversity of photographic objects that’s out there. Whereas photography circa 1960 was primarily silver-gelatin prints—what was being exhibited, what few prints were being shown—that’s what contemporary photographers were making, almost entirely silver-gelatin prints. Now you have not only all of the historic material, but also you have new work in all of these forms that are available to collectors. And that gives photographers a much wider tool kit or repertoire of ways in which they can make their work, and it gives collectors a much larger diversity, and I think a very fascinating diversity, of objects to pick from.

The New, Rule-breaking Photographers Inspire A.D. Coleman to Kick Off the Dialogue

So, to get back to what I was saying, this cohort that began to emerge from schools, in the photo-education programs, in the 1970s—late 1960s, actually—first of all, this was the cohort that attracted me, to some extent, to being a critic. I was interested in the older material by Edward Weston and [Ansel] Adams and Wynn Bullock and Paul Strand and André Kertész and all of those figures, but I don’t think I would have wanted to become a critic of photography if I had not felt from people of my own generation a kind of energy about the medium, including an energy towards challenging many of the traditions. That was happening in the work by younger photographers that was emerging at the time I began doing my writing.

A. D. Coleman lecturing at Copenhagen’s Fotografisk Center.

©1994 by Henning Steen Wettendorf. All rights reserved.

So that cohort, in effect, became a very, very knowledgeable preservationist base for the medium, and a very knowledgeable collector base for the medium. And, in fact, the first time I saw many historical objects in photography, whether that was prints by, let’s say, some of the great 19th Century American landscape photographers, or whether it was daguerreotypes, or those curious objects of different kinds, what I think of as photo-kitsch—or what we now call vernacular photography—the first collections of those that I saw were collections that photographers had built, because they were very fascinated with the prehistory of their work. And many of them developed wonderful collections of all kinds of material. And that’s actually been a tradition in photography. You have Berenice Abbott preserving the work of Eugène Atget, and Lee Friedlander preserving the work of E.J. Bellocq, and many other instances of photographers finding the work of their predecessors and recognizing its significance and conserving it for the future.

Once you have a collector base, you have a market, so it’s hard to say which came first, the chicken or the egg. But you did have, more or less at the same time, this collector base emerging, galleries emerging, and new photo programs being created. So you had more and more such people. Museums either adding departments of photography or expanding their existing departments of photography, beginning to build their collections. The start of a serious auction scene for photography. The rise of a number of non-profits, what we used to call alternative arts organizations, specializing in photography—the Center for Photography at Woodstock, for example, San Francisco CameraWork, there were others dotted all over the country—many of whom held fundraising auctions of donated work as a way of subsidizing themselves, so that those auctions were, and still are, a very simple way, an inexpensive way, for people to enter the field of collecting. With much of the material priced, again, in the low two figures; back then, $50, $100 would get you a very well-made, well-crafted print by someone just emerging, who may now be a famous photographer.

And the photographers, to their credit, including even the very well-known ones like Jerry Uelsmann, were extremely generous in supporting those fundraising auctions by donating material to help those alternative organizations subsidize their ongoing activities and operations.

And part and parcel of that was the emergence of a critical dialogue about photography. Because once you have that kind of audience, you have a readership for criticism and historical writing and theory. So those people, in effect, became some of my readers, some of my audience, and the audience of my colleagues as they emerged a few years later.

PhotoWings: Can you talk a little bit about what kind of writing that is?

A thoughtful-looking A. D. Coleman, photographed in New York, 1987.

© f.stop Fitzgerald. All rights reserved.

The Role of the Critic

A.D. Coleman: Part of what builds an audience for a medium, and helps an audience for a medium sort out the work that’s being done—and part of what I think at least some practitioners find useful, and think about in relation to their own work, at least those concerned about communicating to an audience—is the existence of an actual critical dialogue. By that I mean a number of critics writing from different standpoints about the work, pro and con; because that’s really what a critical tradition is in the classic sense, as defined by Hugh Kenner, who called the critical tradition “a continuum of understanding, early commenced." By which he means early in the life of the work. Meaning that we don’t really understand the work thoroughly unless we know what the people of its own time thought about it and then what subsequent generations have made of it.

Part of what builds an audience for a medium, and helps an audience for a medium sort out the work that’s being done… is the existence of an actual critical dialogue. We don’t really understand the work thoroughly unless we know what the people of its own time thought about it and then what subsequent generations have made of it.

Part of my experience coming out of working as a writer (that’s my background, English literature and creative writing) but also as a young jazz fan was the importance to me—in one case as a performer, as a writer, but in the other case as a listener—of the critical dialogue around both those media. So to come to photography and discover there was no such dialogue, and there really had not ever been—except for a few little spotty passages—such a dialogue, and that there was therefore, no "continuum of understanding, early commenced," was actually quite shocking. I mean, it was really startling, because here you had a major medium of communication without a literature. It just seemed to me that there was work to be done there, productive work and exciting work, and I just jumped in with both feet. I’ve told this story in some of the introductions to my books; basically, an opportunity presented itself and I walked through that door.And that did not exist in photography at the time I entered the field. There had been sporadic phases of criticism in the medium, the most extensive of which was probably the circle around Alfred Stieglitz and the Photo Secession in the nineteen teens, 1920s, while he was publishing Camera Work. But neither before nor after that is there really an energized critical dialogue aimed at a general audience, not just aimed at photographers.

PhotoWings: How was your work received, since it was something new?

A.D. Coleman: On one hand, it was well received by some. By others, it was challenged simply because I was not a photographer. The only people who had been writing about photography on a steady basis prior to that had been photographers, most of them writing in magazines like Popular Photography. This would not have happened, I imagine, in any other medium: My editors would get letters saying, “Why don’t you get a photographer to write about photography?” Now, you would never see a letter saying, “Why don’t you get a dancer to write about dance?” or “Why don’t you get a film director to write about film?” or “Why don’t you get a painter to write about painting?” Not that they haven’t, because they have. But the idea that it was an imperative that one be a performer in the medium to write about it was a peculiar attitude in my experience, peculiar to photography. And that took a while, but that eventually ebbed. Now, of course, many of my colleagues are not photographers. But I was uncommon in that regard, as someone writing steadily about photography but not a photographer. So that was perplexing to some.

And, of course, regardless of that issue, the various positions I took over the years generated levels of controversy and dispute, which is to my mind part of what it’s about—that’s what criticism is for. It’s a sounding board. It’s individual opinion. It’s not the word of God. It’s not even necessarily the permanent conviction of that critic. It’s what that critic thinks at that time, which may change over time—and I have written pieces in which I have changed my mind about this or that body of work.

So I think we have to understand criticism, any critic's work, as provisional and temporary and for the moment, and the best that the critic can do to engage with the work at that particular juncture. And that it’s ultimately just an opinion. It may be a better-informed opinion—not all opinions are equal. It may be a more solidly based opinion, and a more informed opinion, and a more intelligent opinion than another, but it’s an opinion, not a fact.

The various positions I took over the years generated levels of controversy and dispute, which is to my mind part of what it’s about—that’s what criticism is for. It’s a sounding board. It’s individual opinion. It’s not the word of God.

So, in a certain sense, I was in a position, probably a fortunate position, of being able to invent what it meant to be a photo critic with no real major previous models to go on. The closest previous model was Sadakichi Hartmann, who was one of the two main critics in the Stieglitz circle in the nineteen teens and the 1920s, and wrote very extensively about photography, but also wrote widely on other arts, and was also a poet and a fiction writer, and was described by Edward Weston as the best interpretive dancer he ever saw. And was known as the King of Bohemia, strolling through Greenwich Village with a cape and a broad-brimmed hat.

I didn’t really know much about Hartmann when I was starting out—I learned about him later—and I’ve since taken him to be a kind of role model, I guess, on a certain level, or a significant precursor. Not so much with all that other stuff, but simply because he was very involved with the discourse in photography and a committed writer about it—in his case, I think, for about 20 years. He wrote some 700 or 800 essays about photography alone, quite aside from his other writings.

So, because I didn’t know as much as I know now about Hartmann, I didn’t even have him as a role model. So I just had to ask myself, what does a new critic in a new medium do? If you’re going to invent photo criticism, what does it mean?

And to a certain extent, my writing is an answer, or a set of ongoing and evolving answers, to that question: What is the work of a critic? What does a critic do? And, of course, what does this specific critic—me—do, which is not necessarily what another critic would do.

I had to ask myself, what does a new critic in a new medium do? If you’re going to invent photo criticism, what does it mean?

PhotoWings: How does someone, such as yourself, handle bad press that you might get, or controversy around things you do?

A.D. Coleman: Well, on one hand, controversy is fine and welcome; and there are pieces I write specifically to be controversial and contrarian. Because as the dialogue evolves, and more and more people are writing, one of the questions I ask when a body of work is being considered by my colleagues as well, when I see their writing, is, "What do I have to add to this discussion?" Which is something I consider in a social situation too. If, in other words, it’s “Just like he said"—I mean, “I agree with whoever it is” —then what I would have to say has already been said, and generally I won’t write that essay.

On the other hand, if I think there’s something that’s been missed, or another way of looking at the work, or some perspective on it that adds to the discourse, then I may very well write that kind of piece. And there are times when I look at the overall discourse, and I realize there are holes in the literature that need to be filled. I wrote a piece that’s very well known in 1976, called "The Directorial Mode," which was a piece about staged photography. And I wrote that very specifically because a lot of such work was being done by people in photography, a lot of such work was being done by people outside of photography doing now what we call "photo-based art." And none of them had any idea, really, of what the actual history was of that approach to making pictures. The art world was acting as if artists had invented this, and the photographers didn’t know that they had basically invented this, and they had precursors going back to the 19th Century.

So I wrote an essay very specifically to try and define that approach to photography. That became a reference point for many people, and I knew that was an important essay when I was writing it; I mean, I knew that was filling a very important historical gap, and many people would find their lineage in it. And many people have told me since that they did.

So sometimes I write pieces for that reason—just because, something needs to be said in that way, or something needs to be clarified from an historical standpoint.

Then sometimes there are other pieces where I wait for someone else to write the essay—because it’s a dirty job, it’s a kind of fighting essay, and I hope that someone else will do that. You know, a contentious piece. And if they don’t, I realize that somebody really needs to. Then, at a certain point, I say, look, okay, it’s your job. So I write those pieces sometimes too, and they either do or don’t stir up controversy. But I see that as also part of the job of the critic: recognizing what the state of the discourse is around the particular subject, and asking oneself if there is something else that needs to be said, and am I the one to say it, for whatever reasons. Is that interesting? Do I want to take that on? What is it you want to say about that?

Sometimes there are pieces where I wait for someone else to write the essay—because it’s a dirty job, it’s a kind of fighting essay, and I hope that someone else will do that. You know, a contentious piece. And if they don’t, I realize that somebody really needs to.

PhotoWings: So if someone criticizes something that you said, and you don’t agree with it, you take it personally, how do you …

A.D. Coleman: The thing we have to recognize always, if we’re engaging in criticism, is that unless the criticism is directed at the person, which I think is an abuse of criticism, then the criticism is about the work, not about the person. And as the maker of the work, you have to separate yourself from that.

And then as the reader of the piece, and as a writer, of course, you have to separate your feelings about the maker from your feelings about the work. What you should be addressing, I think, as a critic, is the work, and not the person. But, of course, our work comes out of us, it’s very intrinsic to us, and it’s very reflective of us, and we have a very direct parental relationship to it, so it’s a little bit like telling a parent "I’m talking about your kid, I’m not talking about you."

Of course, on some level it’s very hard to separate those out, even if this is true, and it is about the kid and not about you, and that’s how it’s intended. So of course as a maker myself—of my own essays, and of other things I do (as a poet, etc.)—there’s a certain level on which my first response, if someone says something negative, is that I’m going to kill them, naturally, yeah … wipe them off the face of the earth. But I’ve learned to take criticism fairly well. And again, unless I feel it is genuinely malicious in its purpose, which it sometimes has been, I welcome it, partly because of my critical role. The purpose of critical activity is to stir up discussion, and that includes dispute, and contention and contradiction and so on.

I try to make my arguments as seamless and foolproof as possible. That is, I try to cover the bases. There’s always certain kinds of “What about X?” and of course, there’s the possibility just of the legitimate disagreement over various things, and that’s . . . again, I think that’s part of the energy of a serious critical dialogue in the field, that there are these disputing positions and that, I think, draws people to a medium. I don’t think it drives them away, I think it makes it attractive, because it’s evidence that, for one thing, people are taking this material seriously, and it’s also a sounding board for you to bounce your own responses off.

As a maker myself—of my own essays, and of other things I do (as a poet, etc.)—there’s a certain level on which my first response, if someone says something negative, is that I’m going to kill them, naturally, yeah … wipe them off the face of the earth. But I’ve learned to take criticism fairly well.

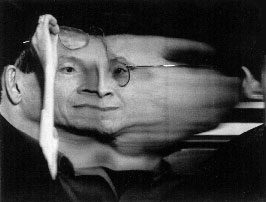

A. D. Coleman reimagined by photographer Andy Davidhazy, Houston FotoFest.

©1994 by Andy Davidhazy. All rights reserved.

What Happens at Photo Festivals—and Why We Should Care

PhotoWings: So we’re currently atFotoFest, and there’s a gathering of critics, collectors, curators, educators from all over the world. What do they bring to a discussion and how do they differ?

A.D. Coleman: Oh boy! Well…

PhotoWings: Culturally?

A.D. Coleman: I think we have to be a little more precise. What this really is here is a marketplace environment for photographic projects, and you’ve buyers and sellers. And you’ve got a system, a very elaborate and very well-constructed system of 20-minute cold calls, if you talk about marketing procedures. So photographers basically draw lots, although it’s more sophisticated than that, and they get a set of 20-minute cold calls with people who might be users of their material, whether that’s a user in terms of putting on an exhibition in a museum, or whether that’s putting on exhibitions and actually repping the work in a gallery context, or whether that’s publishing the work in book form, or publishing portfolios of work in a magazine, or whether that’s buying a work in its physical form for collections.

And both sides, in a sense, are filling out their dance cards. The reviewers looking at the work have effectively got dance cards: they’ve got projects, they’ve got exhibition schedules, they’ve got holes in their gallery’s repertoire of materials, or they’ve got issues of magazines to fill, or they’ve got a season's worth of books they’re going to publish, and they’re out rustling the bushes looking for work, and this is an efficient way of doing that. And from the standpoint of photographers, it’s an efficient way of putting your work in front of those people, if you've got thick enough skin that this idea of a 20-minute cold call, and five or six self-marketing opportunities . . . it’s speed dating! Speed dating for these people on both sides; and it’s willing, it’s voluntary on both sides.

PhotoWings: So what do you find the different cultural approaches are? There are people here from Poland; there are people here from Russia, and from Lithuania. How do they see the same work differently?

A.D. Coleman: Oh, you’d have to ask them. I’m not sure I could answer that. They certainly do, because every culture has its own set of reference points; when we’re looking, you and I, at Russian work there are all kinds of cultural references we’re missing that any Russian would pickup in a minute, and the same with Chinese work, and so forth. But vice versa: When they look at U.S. work, or Latin American work, there are all kinds of cultural references they’re missing.

Photography is not an international language. We like to think that the imagery crosses borders with its meanings intact, and it does cross borders, and it is interpreted well on the other side, but the meanings don’t travel automatically with it. On the other hand, these are also fairly sophisticated lookers at pictures; they know, to some extent, how to compensate for their own—I don’t want to say lack, because that sounds like a deficiency—but they know how to compensate for the cultural references they don’t have. They know, for example, if they are a Latin American curator looking at Russian work, that they will need some kind of essay from a Russian perspective to help them contextualize that work for their audience, just as they know they’re going to have to write an essay themselves from their Latin American perspective to contextualize work for the audience from the Latin American standpoint. So it’s not just a crapshoot out there, not just random; they know, to some extent, how to offset what gets lost in translation in that situation.

Photography is not an international language. We like to think that the imagery crosses borders with its meanings intact, but the meanings don’t travel automatically with it.

PhotoWings: What can these people learn from one another?

A.D. Coleman: The reviewees?

PhotoWings: And reviewers, well, and both, and the photographers among themselves.

A.D. Coleman: When you come to an event like this, you get to see—because there’s a great deal of work from all around the world at this festival and the other photo festivals, and now there’s a whole network of photo festivals around the world—you get to see the diversity of work that’s being done in other places. You get to see new techniques, new variations on techniques, and in terms of object-making, or even image-making. Now a lot of it is digital work, and so people use digital imagery in a lot of different ways.

We talk about there being something called "world music," and if there is something called "world music," then there is something called "world photography." And if you really want an entry into "world photography," a festival like this is one of the best places to start. Also, at these festivals, I see work, I would say, often five to ten years before I see it in the museums and galleries.

So in terms of knowing what’s really happening, right now, I would say that just about any of the festivals that I have visited, and certainly any of the big established festivals I have visited, will give you a clearer sense of what’s happening in the medium now than what you’ll get from the galleries and museums. There’s a trickle-down effect, based on what we talked about before—you know, this filling-out-the-dance-card effect. There’s a certain filling-out-that-dance-card effect that really results in bringing to these institutions work that these curators did not know before, but at the same time it’s going to take several years . . . I mean that if someone finds someone here today who says, "Yes, I want to give you a museum show," it’s probably going to be three or four years before that show happens, just because that’s the timeframe in which such institutions operate.

[At photo festivals] you get to see new techniques, new variations on techniques, and in terms of object-making, or even image-making. Now a lot of it is digital work, and so people use digital imagery in a lot of different ways. I see work often five to ten years before I see it in the museums and galleries.

PhotoWings: So most of these places have exhibitions, and they have auctions. Would this be a good place … ?

A.D. Coleman: The festivals, you mean? Yeah, all of them are really based around exhibitions. Some of them use an informal meeting-place environment, which is true of [Les Rencontres d’] Arles — which is in the south of France, and which is the granddaddy of all the photo festivals. Some of them use a more formal organized portfolio-review system, like this [FotoFest]. Some of them offer lectures and workshops, some of them don’t. Everybody picks from a certain menu. But the core of the festivals, I think almost always, is a set of exhibitions, some of which are imported, and some of which are created by the festival directors themselves, or by curators they engage for that purpose.

PhotoWings: So, you think this would be a valuable place for collectors to start learning?

A.D. Coleman: Well, I certainly think that, as a place to come and look at the diversity of work being done, it’s a great place to see that. It’ll give you much more of a sense of the international photo scene than you’ll get just about anyplace else. Most of them publish catalogues, and you can buy those catalogues, if you can’t get to the festivals. But there’s nothing like seeing work in its physical form, I think, to really give you a sense of what it’s about. And then, of course, if they’re actually developing serious collections themselves—it wouldn’t be right for a starting collector—they might end up reviewing; there are several collectors here who are reviewing portfolios, because they buy work here. So it’s valuable from that standpoint, too. And of course they get to network with people in the field, including everyone I mentioned: curators, critics, historians, gallery people, etc. So it’s got all those values.

PhotoWings: And have people gotten good values in terms of buying at the auctions, or buying directly from the photographers?

A.D. Coleman: You’d have to talk to them about this, but I’m sure that they have. A lot of work does get bought here, and I know that at FotoFest’s latest auction—they do a fundraising auction every year, and the work is donated, most of it, by people who have been beneficiaries of FotoFest’s sponsorship in the past—I can’t remember what the exact number is, but they were very happy with the results. Much work sold is actually above its gallery prices here, which may not be the greatest thing to tell collectors. But there is very active purchasing going on here and, of course, many people have sold individual prints to collectors, to galleries, to museums, etc., here. So it’s a very good exchange place in that way, on both sides—for the buyers and for the sellers—because most of the photographers have come ready to do business. Here, when you’re buying from the photographers, you’re buying directly from them, so you’re not dealing with the gallery mark-up.

PhotoWings: Sometimes.

A.D. Coleman: Not always, but in many cases, you’re buying direct from the photographers.

PhotoWings: Right, right. And just one of the things that PhotoWings has been discussing with you is that you are very interested in education…

A.D. Coleman: Mmm ...

PhotoWings: And you have a new Web site. Perhaps you’d choose to talk about that a little bit.

A.D. Coleman: I’ve taught since about 1970, so I've taught pretty much from the beginning of my work. Nowadays, I teach short seminars and workshops, including a seminar for collectors. But I’ve set up several web sites for the educational community, and one of them is a Web site called the Photography Criticism CyberArchive, at photocriticism.com. That’s a very deep online archive of many people's writings about photography from the 1830s onward, including the complete Pencil of Nature, by [William Henry] Fox Talbot, and on up through contemporary writers on the medium. That’s a subscription-based Web site; it’s available either through institutional subscription or individual subscription.

And the most recent Web sites is one called The New Eyes Project, and that is at K12photoed.org. It's specifically set up to service the K through 12 photo-education community, as a resource, and as a place for an open forum. The forum is set up. There’s going to be readings online, there’s going to be various resources online for that community, there’s going to be help in networking and fundraising, and a number of other projects like that.

And then, of course, there’s my Nearby Café, at nearbycafe.com, which has been up and running since 1995. That’s a multi-subject electronic magazine with a lot of material about photography, but material about all other kinds of subjects too, by myself and other contributors.

PhotoWings: Great. Thank you, very, very, very much.

A.D. Coleman: You’re welcome.

About A.D. Coleman

At a time when photography criticism was essentially non-existent, A.D. Coleman blazed the trail by sharing his unique and sometimes controversial insights in the form of 2,500 essays and several books on photography.

Named among the 100 Most Important People in Photography by American Photo, his influence on the field has been significant. “Coleman has breathed fresh air into the otherwise moribund corpse of photography criticism and almost single-handedly kept its spirits alive,” says noted photographer, author, and educator Bill Jay.

A pioneer of modern photo criticism whose award-winning writing is accessible to the layperson, A.D. Coleman was the first photo critic for The Village Voice (1968 to 1973), The New York Times (1970 to 1974), and the New York Observer (1988 to 1997). He has also been a columnist for numerous photo magazines including Camera Arts, Camera 35, Camera & Darkroom, and Photo Metro in the United States, Ag and The British Journal of Photography in England, Fotografi in Sweden, and Juliet Art Magazine in Italy. He has appeared on NPR, PBS, CBS, and the BBC.

Today, he continues to write for various publications and also runs educational Web sites including The Nearby Café, the Photography Criticism CyberArchive, and The New Eyes Project.

For Your Bookshelf

If you’d like to read some of A.D. Coleman’s reviews and commentaries from years past, you’re in luck. He has released several compilations of his work in book form.

Light Readings: A Photography Critic’s Writings, 1968–1978 (University of New Mexico Press) is a collection of Coleman’s early writings, including his very first essay for the Village Voice and his controversial pieces on John Szarkowski and Susan Sontag.

In Depth of Field: Essays on Photographs, Lens Culture and Mass Media(University of New Mexico Press), a collection of his writings from 1978 to 1996, Coleman discusses various issues such as where photography came from, the function of criticism, and the ethics of street photography

Critical Focus: Photography in the International Image Community (Nazraeli Press) includes Coleman’s coverage of various photographers—from Barbara Kruger to Robert Mapplethorpe to Sally Mann —from 1989 to 1993. It also includes Coleman’s take on various issues in photography, from censorship to public funding for the arts.

A.D. Coleman on the ’Net

A.D. Coleman, ever the pioneer, became the first photography critic to set up shop in cyberspace when he launched his online newsletter, C: the Speed of Light, in 1995. The newsletter—read by photography teachers, students, and others interested in the craft—features new essays and lectures by Coleman in each issue.

C: the Speed of Light eventually broadened to become The Nearby Café, a dynamic Web site where visitors can peruse work by various photographers, artists, and writers. The Nearby Café also features a History of Photography Calendar, a searchable compilation of important dates in photography history.

The “New Eyes” Project: Introducing Kids to the Wonders of Photography

An ardent supporter of photography education, A.D. Coleman recently established The “New Eyes” Project: Teaching Photography to the Young, an online resource for educators, students, and others involved in K–12 photography. The Web site will include readings, lesson plans, a forum, and other resources, as well as networking and fundraising opportunities.

A Curator’s Musings

“[A.D. Coleman] is a very intelligent writer, and he photographed some himself as well, and so he could understand what it was to get a good picture. He would talk to the photographers, there would be stories, sometimes about how the pictures got made, the attitude. He approached things understanding not just the thing in front of the camera—the subject—but what attitude the people brought to what they were photographing, and that’s a big step, because that puts it on a different plane than most people who say, ‘I’d like to get a good picture of this rose garden because I just love it.’”

—David Travis, photo curator, The Art Institute of Chicago