Brigitte Carnochan – Reinterpreting Text and Images

This is a preview of an upcoming, deeper feature on Brigitte Carnochan, exploring her series, Imagining Then. In the PhotoWings & AshokaU webinar, we highlighted this exceptional work to help inspire the webinar participants as they create their final projects.

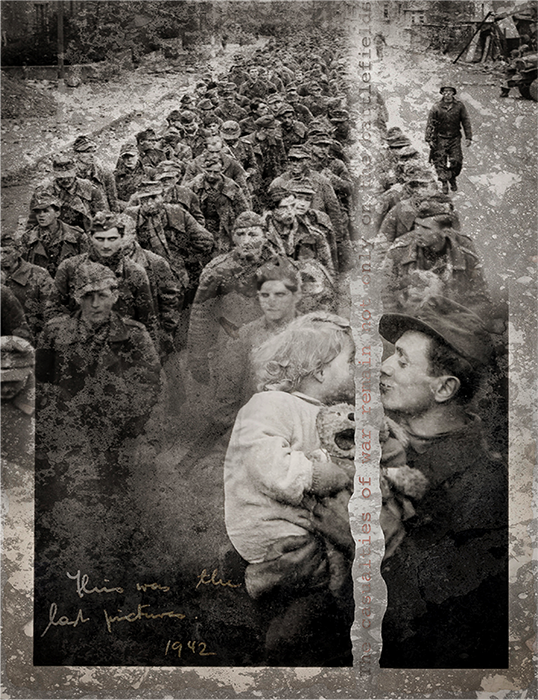

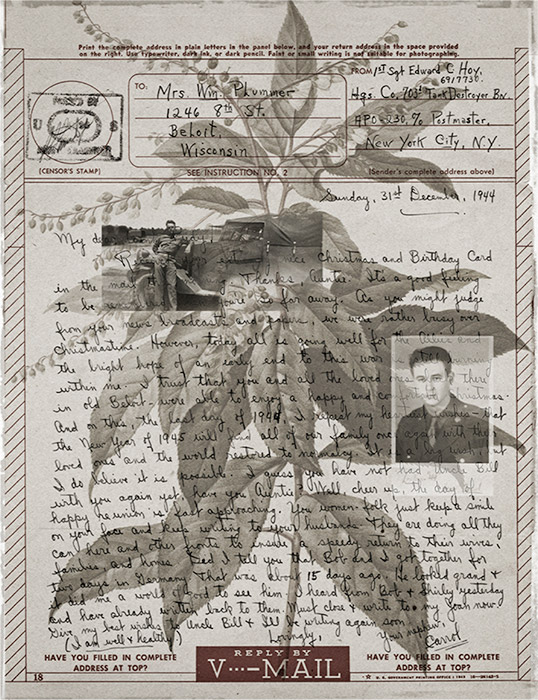

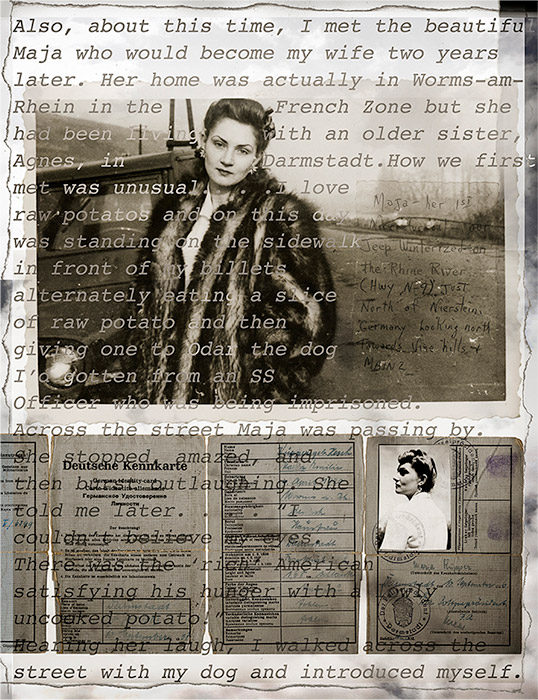

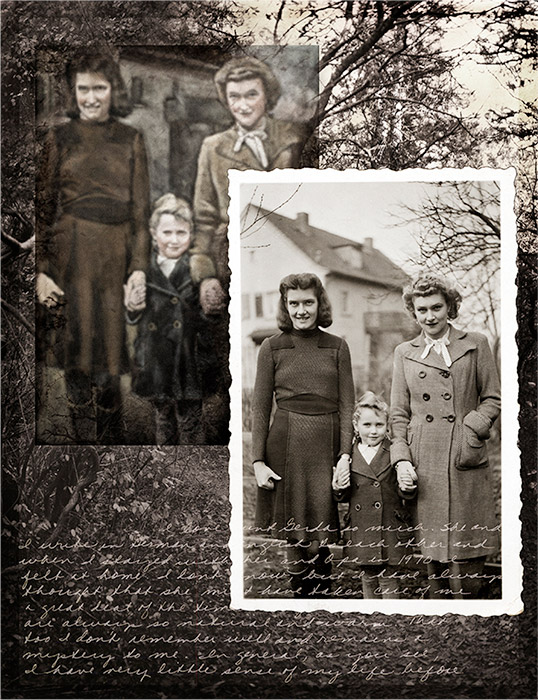

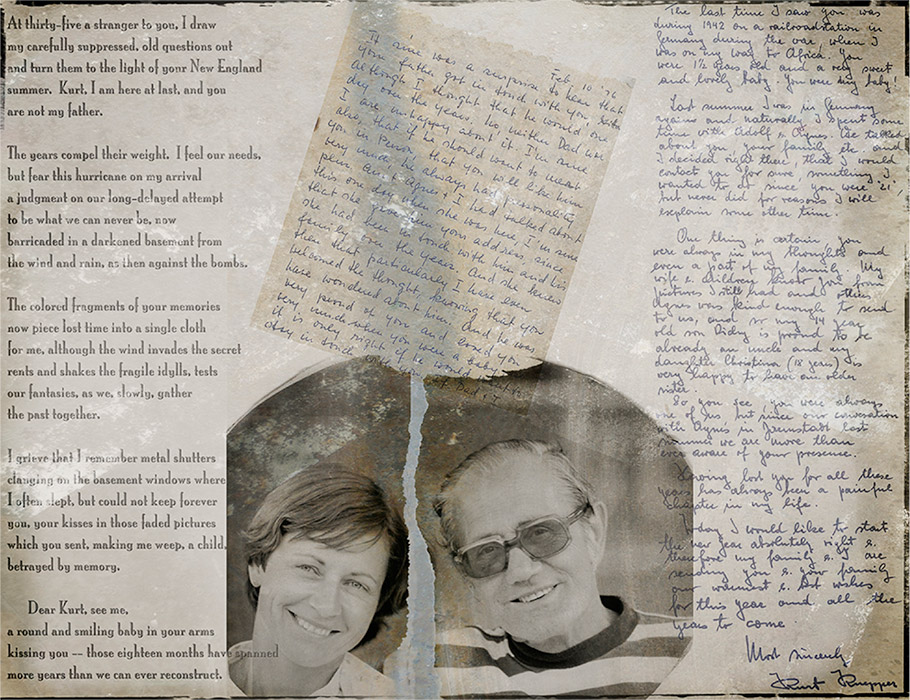

Brigitte Carnochan is a well-respected fine art photographer and an articulate educator, currently teaching at Stanford University. In Imagining Then, she shares her uniquely personal story in words and memories through a collaged tapestry in platinum-palladium photographs. Acting as much of a historian as an artist, Brigitte takes the odds and ends of old photographs and documents and joins them together to create a richer, meaningful narrative of her family history.

Brigitte was born in Germany during the Second World War. Her parents separated when she was three. While fighting for Nazi Germany, her father was captured by American troops and remained estranged from her until 1976. Shortly after the war, she and her mother immigrated to the US to begin a new life. When Brigitte was 35, her father finally made contact with her. After reconnecting to her birth father and his family, she spent the next 10 years trying to understand and interpret what she learned. Imagining Then was the product of her journey. Recently, Brigitte sat down with PhotoWings to talk about the project:

Brigitte Carnochan - Discussing "Time Like a River"

Old photographs tease out fragments of a memory— a laugh, a sigh, a conversation the camera interrupts and then suspends across time. Looking at photographs and documents that came to me after my parents died, I’m struck not only by how much I’ve forgotten but really how much the past comes rushing back when called. Sometimes forgetting is simply being afraid to remember.

There were all kinds of reasons that I had been afraid to delve into my past because I knew nothing about my German father, and I was afraid, in a certain way, to ask my mother about him. It was clear that she didn’t want to talk about him, but I was afraid that he was the worst of the worst— that he had been a Nazi. Who knows what he did during the war? I wasn’t sure I really wanted to know all that.

Emily Dickinson had an expression in one of her poems, a great line: “Tell all the Truth but tell it slant- / Success in Circuit lies / Too bright for our infirm Delight / The truth’s superb surprise.” The truth is one thing for one person and one thing for another. Neither of the people are lying, but their memory of an event is simply different. I’m sure if my three parents, my American step-father, my German father and my German mother were still alive, and they saw this project that I’ve done — which alas, they’ve never seen — they would have their own experience of how true it was to what actually happened.

"Time Like a River", Image © Brigitte Carnochan

All I’m trying to do with the project is to imagine what the truth might have been. Since I was born in ’41, at the age that I was in this period from 1941 to 1947, all I can do is imagine the truth. People often refer to this body of work as “Remembering Then,” but it’s very deliberately called Imagining Then — because then — because I can’t actually remember very much of those years. But that’s the power of the photographs that survived: Through looking at the photographs, I can begin to imagine around the edges how that life might have been and combine it with conversations that I remember in terms of the family and also with visits back to Germany over the years and talking to relatives about minor things— remembering stealing tomatoes out of my grandmother’s garden, for example.

In these images, I’ve tried to draw a map of my life by taking the random but tangible artifacts my parents left behind, the both of them— saved certificates, passports, and official documents. I think I did this in part because it was so hard to get those documents initially. They saved everything, so I would look over those. One of the goals of this project for me has been to use my personal material but to put it into a historical context. Using my personal experience and leaving it there would be of interest to me and possibly to my family, but I thought it might be important to place these things in a broader historical context, so that more people could relate to the experiences that I had.

It’s not just to bring those years back for the people who experienced it, but to try and show those years to people who were never there. That, of course, is one of the powers of photography. With the photographic image, you can put people who have never had that experience into a situation where they feel the power of that moment, where they feel as though they might have been there.

I didn’t want my images to be so complicated that people would look at them and say, “Wow, she’s really good at Photoshop.” I just wanted to be able to juxtapose the things that I wanted to juxtapose in a certain way — and tell the story that way. When I felt confident I could do that, I sat down at the computer, and the whole thing came together in less than a year. I worked very hard, but the pieces just all fell together. I guess I’d been thinking about it for so long, for eight or nine years.

People look in these images, and whether their life story is anything like mine or not, I think it calls up in their own memory a piece of their past that they see merging with what they’re looking at in my image. So, that’s been one of the rewards. We haven’t exactly, as a human race, gotten over our proclivity to rush to war, to treat each other in indescribably awful ways. Anything that counters that particular tendency to use power and might against the weak and oppressed might be a good outcome.