Bicycles and Bloomers: How Bikes Helped Revolutionize Women’s Lives

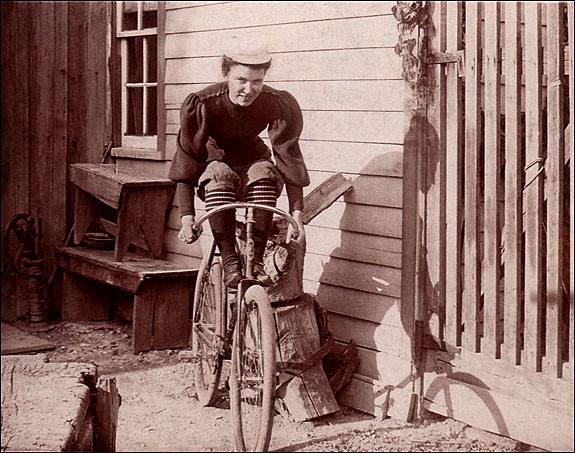

Photographer unknown, A lady Scorcher, outfitted in bloomers and ready to ride, Circa 1900. Card stock, American Photo. Collection of Lorne Shields.

“Scorchers were fast, reckless bicycle riders—sort of the hot-rodders of their day,” says Lorne Shields, a respected bicycle photography and ephemera collector. “Take a peek at her face—she has a charming, wicked smile, truly letting her photographer know of her independence. Perhaps the only thing missing is her tattoo!”

Bicycles and Bloomers

Glance at an old photo of a Victorian lady with her bicycle, and you'll likely notice a mischievous glint in her eye. Until the late 19th Century, women had to rely on men to get around—so that bicycle was her freedom ride!

As women took up bicycle riding, they began spending more time in the male-dominated public sphere and adopted more freeing, bicycle-friendly fashions—causing quite a scandal at the time. In fact, in 1896, Susan B. Anthony declared:

“The bicycle has done more for the emancipation of women

than anything else in the world.”

The bicycle was introduced commercially in the U.S. in 1868, had almost disappeared by 1870, and made a strong comeback when a group of high-wheel bicycles captured the limelight at the Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia in 1876.

Ladies were able to ride tricycles fairly well, but riding these two-wheeled wonders was certainly no easy task. American women were bogged down with oppressive skirt-like undergarments made of heavy horse-hair and ankle-length crinolines or petticoats, which made peddling a bicycle difficult, if not dangerous.

Photographer unknown, A lady wearing “proper attire” astride her bicycle, Circa 1898. Cabinet card, Collection of Lorne Shields.

Black (first name unknown), A trick-riding lady on her Velocipede, Circa 1869. Carte de Visite, Collection of Lorne Shields.

One early lady cyclist, Mrs. George D. Johnston, described the disastrous end to a summer bike ride she took in the Ladies Standard Magazine:

“Some friends and I were riding one day against a very heavy wind, when it caught my skirt and wound it around my pedal, throwing me," she said. "The rapid gait I was going caused the force of the fall to break my arm. It laid me up six weeks.”

Riding bicycles was fun, but the criticism that came along with it was not. Polite ladies were expected to wear traditional, skirt-like undergarments, but some gutsy women bucked convention and began donning caftan-style pants called bloomers or knickers, which had been invented by women's advocate Elizabeth Smith Miller. Pictures of these new garments caused quite a stir. (Today's underwear, in fact, evolved from these undergarments, which were also called drawers, pantaloons, and pantalettes.) Bloomers—combined with trousers or split skirts as outerwear—soon became a fashion statement for cycling ladies.

Photographer unknown, Three proud ladies show off their bicycles, date unknown. Collection of Lorne Shields.

A handful of fierce, feisty ladies were racers and even trick riders. Representations of photos of both trick riders and everyday women, in the form of etchings or illustrations in popular ladies' magazines, likely inspired other women to put on bloomers and take up bicycle riding themselves. Women may also have run across personal photos of women on bikes.

Women who rode had to be tough, because they faced plenty of criticism. Many people were shocked at the idea of unescorted ladies venturing into "unsavory places" where they might be attacked or seduced.

Others were simply threatened by the unfamiliar. Ladies, whose domain had been the home, were now out and about, confidently claiming their independence. Generally, they couldn't go too far, though. Roads were slowly being adapted for the new craze, so routes were somewhat limited.

While lady cyclists were a subject of hot debate, their bloomers continued to spark controversy as well. One outspoken critic in England called them "an abominable invention which produces disorders in abundance." What types of disorders, exactly? Some feared that if women began wearing pant-like garments, which looked similar to men's clothing, they might begin adopting other masculine traits as well.

But happily for cycling ladies, an influential aristocrat had joined their ranks in the late 1880s. None other than Queen Victoria began riding a tricycle for adults and also gave her daughters bicycles, likely spurring other women on. If bicycles were good enough for the queen, women likely reasoned, perhaps they weren't so bad after all.

As the late 1880s progressed through to the mid-1890s, as bicycles became less expensive and more woman-friendly and bloomers became more popular, cycling rocketed into widespread popularity. And women, with their first taste of freedom, rode into the future that looked very bright indeed.

PhotoWings would like to thank Lorne Shields for his generous help with this story and for the use of his photographs from his exceptional collection. Shields is an avid and respected collector of historic bicycles, related posters, memorabilia, and ephemera. In addition, PhotoWings would also like to thank bicycle historian Andrew Ritchie for his help.