Antony Penrose – Lee Miller in the War

She was the only photographer in the whole area— and that made her a combat photographer.

Antony Penrose, Director of the Lee Miller Archive

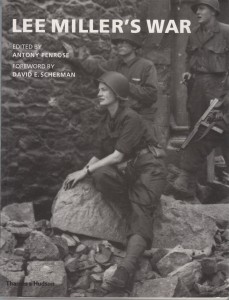

PhotoWings had the privilege to speak to Antony Penrose, son of the compelling Lee Miller and director of her archive. Lee Miller was an important photographer from the 20th Century. Her contributions to fine art photography notwithstanding, Miller is widely renowned for being one of the only female combat photographers in the Second World War. Miller did not intend to cover direct fighting. However, caught up in the front lines shortly after D-Day and understanding her responsibility to record history, Miller readily took on the role of combat photographer.

As founder and director of the Lee Miller Archive, Antony Penrose has helped to ensure his mother’s legacy, which in turn has allowed it to be reevaluated by the world. Her photographs have now been exhibited internationally in many major museums, including the Getty Museum in Los Angeles, the San Francisco Museum of Modern of Art, the Victoria & Albert Museum in London, the Jeu De Paume in Paris, and the Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts in Moscow.

Below, listen and read along to Penrose recounting Miller’s experiences during World War II. What follows is a compelling story about an extraordinary person in unexpected circumstances. Thinking she'd work behind the scenes documenting stories with less exposure like Britain’s “wrens,” Miller unexpectedly found herself not only in the middle of combat, but in one of the biggest stories of the war. Miller went on to cover the liberation of the Buchenwald and Dachau concentration camps for Vogue Magazine. Miller’s inspiring, personal story and the impact of her unexpected photos demonstrate the power of photography and also the toll they can take on a photographer.

Learn more: The Lee Miller Archives

Lee Miller in the War

Lee went from shooting fashion to covering war because I think she felt that fashion at that time—and I’m talking now about 1939, 1940—fashion was a bit trivial. Because here she was in England, knowing full well that the people that she loved most in the world were in France, which had just been occupied, and they were facing all kinds of dreadful threats every day. Most of the surrealists—a great many of the ones that stayed in France—were part of the resistance movement. And although in Britain it was not known what they were up against, it was fairly obvious that they were in great danger, and she could not sit in England and do nothing while this was going on.

She wrote some crack about, “I’ve eaten the butter, so now I must face the guns.” And she wasn’t gonna rat on her friends by going back to America when she could easily have done so, because she was an American citizen. I think she took stock of the situation and thought, “Well, what can I do?” And what she could do was take pictures, and so that’s what she did.

To begin with, she took pictures of nurses and women sailors in the British Royal Navy—they were called Wrens—then people like the woman soldiers for the ATS. They used to drive trucks and man search lights and do stuff that was actually very dangerous, but interestingly enough, they didn’t get press. And so she was one of the ones who made it her mission to go in and get exposure for what these people were doing. So that was her contribution to the war effort.

She did not intend to become a combat photographer. This happened by accident. She was supposed to be covering a story about the Civil Affairs Department, which is the guys who went in after a battle to straighten out the civilian life and population and get things moving again. She was supposed to be covering them and their activities in the city of St. Malo, the port on the north coast of France.

And when she got there, she found that, contrary to reports, the Germans had not surrendered. They were still fighting a very vicious and vigorous rearguard action from the old citadel, where they were dug into solid rock. And it took the U.S. 83rd Division about five days to persuade them to surrender, and Lee scooped it. She was the only photographer in the whole area— and that made her a combat photographer.

Subsequently, she and David Scherman, her buddy from LIFE magazine, were about 30 days under fire because she covered the incredibly fierce fighting that winter — the winter of ‘44, ’45 — in the Vosges Mountains. The Germans had their backs to their own frontier, and they weren’t gonna give an inch, and they were fighting with tremendous ferocity. The battles were endless and the cold — just the physical difficulties were unbelievable. Well, she was there, and she photographed them. And then when they got through to Germany, she was right with them, and it was still a very, very heavily contested drive right across northern Germany.

This was the moment, though, that the war became very personal for Lee Miller because this was the moment that the rumors about the concentration camps became realities, and Lee visited four concentration camps. She went to Ohrdruf and Penig and Buchenwald and Dachau. She photographed only the latter two, but she photographed them with tremendous penetration and conviction. And the reason for this was because when she arrived in Paris, many of her friends were missing. Many of her Jewish friends had just vanished. The hope was that they would all be found working in some big labor camp somewhere. But when the concentration camps were discovered, and the extermination facilities and so on were all exposed, then it was so undeniably evident that these people would never be coming home again.

And so as she was going around at the camps, she was photographing dead and dying people and looking right into their faces because, in a way, she was trying to find what had happened to her missing friends and maybe to see if she could identify them among all these thousands of starving people. And that, I personally I believe, made an irreversible change in her. I don’t think she was ever the same again after that moment.

About Antony Penrose & Lee Miller:

Antony Penrose is a filmmaker, photographer, author, artist and photo curator — as well as the co-founder of the Lee Miller Archives and The Penrose Collection.

His mother, Lee Miller worked as a photographer, beginning her career in the 1920s.

To say that Lee Miller had a complicated career may be an understatement. She began a modeling career in New York, then moved to Paris to work with surrealist Man Ray before starting her own photography studio. She began by taking street photos and portraits, but later she became at war correspondent in World War II. After the war, she continued to photograph for Vogue, who had published her war images.

Her work moved to covering people. She photographed many of the iconic artists of the time, including Pablo Picasso and Charlie Chaplin. Curiously, her life eventually drifted away from photography, and near the end of her life, she was known mainly as a gourmet cook. She died in 1977.

Learn more about Lee Miller's photographs from WWII in our webinar.