Anne Wilkes Tucker – WAR/PHOTOGRAPHY

Our goal was to create something that is the beginning of discussions, not the end of discussions.

– Senior Curator of Photography Anne Wilkes Tucker, Museum of Fine Arts Houston

Ten years in the making, WAR/PHOTOGRAPHY: Images of Armed Conflict and Its Aftermath premiered at the Museum of Fine Arts Houston (MFAH) on Veteran’s Day, 2012. Through the work of the museum's renowned curators — Anne Wilkes Tucker, Will Michels and Natalie Zelt – this comprehensive exhibition (complete with 600-page catalogue) examines how photography informs and interprets history. In total, the exhibition’s catalog features almost 500 objects from 280 photographers worldwide, taken from the advent of photography through present day.

Now that the second leg of the exhibition at the Annenberg Space for Photography in Los Angeles has closed, East Coasters have the chance to view WAR/PHOTOGRAPHY at the Corcoran Gallery of Art in D.C. The Corcoran hosts the exhibition — proclaimed "arresting" by the LA Times — from June 29, 2013 to September 29, 2013. The Brooklyn Museum will follow from November 8, 2013 to February 2, 2014. Each institution brings its own specialized curation and programming for the travelling exhibition.

Guests to the opening night at the Annenberg Space for Photography watch a documentary about the exhibition. Courtesy Unique Nicole, Annenberg Space for Photography

Looking at its scope and subject, WAR/PHOTOGRAPHY is a unique effort. Before, other exhibitions have approached war through the work of individual photographers or historical events. However, war photography — as an entire subject and genre of photography — had yet to see an encompassing treatment until now. To that end, the exhibition’s curators took an unprecedented step and placed many different types of photographers in the show:

“The military photographers have a different mandate than the newspapers, than the magazine, than the portrait, than the soldiers photographing for themselves — and we try to acknowledge how for whom they’re shooting affects the resulting photographs in the catalogue,” said co-curator Anne Wilkes Tucker.

The organization of the exhibition also speaks to its uniqueness. The show is arranged by the order of events that take place in war, from the opening shots to its aftermath. With this layout, the curators emphasize a universal experience of war. “[War] seems to be part of the human condition.” Tucker explained. “One of the things we consciously tried to do is show how the same experience crossed lines of combatants.”

Recently, PhotoWings interviewed Anne Wilkes Tucker, Senior Curator of Photography at MFAH, to speak about some of the why’s and how’s of WAR/PHOTOGRAPHY. As you read her responses, you can listen along to her voice in each section below.

WAR/PHOTOGRAPHY: Images of Armed Conflict and Its Aftermath exhibition catalogue. Museum Fine Arts Houston, 2012.

Table of Contents

- An introduction to the exhibition

- Why war?

- Divergent perspectives

- Surprises from the research

- Lesser-known pictures

- Putting a light on civilians in wartime

- On snapshots taken by soldiers

- Soldiers’ reactions to the exhibition

- A complicated relationship between soldiers and photography

- Ethical dimensions of war photography

- Emphasis on a common humanity

- What can be learned from this exhibition

- Why photography?

- Interesting Links

The photograph has a power because we can recognize a moment, a situation, a human emotion in them that speaks to us in ways that words don’t.

An introduction to the exhibition

The show is about patterns, types of photographs that occur in every war — across culture, across time, across religion. It’s about the relationship of war — which is an entity all in itself — that is conducted by military forces, either established or insurgent.

We looked at over a million photographs and eventually got that down to a database of 2,000 — which then eventually came down to the 480 objects that are in the show. While we were doing the research, we began to notice that these pictures kept occurring: women at gravesites often hugging or touching the tombstone, people scavenging for food — battlefield death, battlefield destruction.

It’s not chronologically arranged, but in the order of war. Working with military historians, we began to understand how those [pictures] related to the phenomena of war and how it is conducted. It was only very late that we realized that we could organize those patterns into the order of war:

Starting with the advent of war — 9/11, Pearl Harbor, the assassination of the Archduke. Going through then: enlistment, training, embarkation, patrol — and all the aspects leading up to war, reconnaissance. Then, into the fighting. After that, all the stages of aftermath: shellshock, destruction of property, battlefield-dead, burial, grief, medicine, as well as all the backup areas, religion, support of the troops. Through to the end of war, memorials and remembrance.

Several photographers featured in the WAR/PHOTOGRAPHY exhibition appear the opening at the Annenberg Space for Photography: From left to right - Carolyn Cole, Ashley Gilbertson, Nick Ut, Luis Sinco, Hayne Palmour IV and Edouard H.R. Glück. Image courtesy Unique Nicole, Annenberg Space for Photography.

Attack—Eastern Front WWII, 1941. Dmitri Baltermants, Russian, born Poland, 1912-1900. Gelatin silver print, printed 1960. The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, gift of Michael Poulos in honor of Mary Kay Poulos at "One Great Night in November, 1997." © Russian Photo Association, Razumberg Emil Anasovich

A view of the exhibition at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. On the left, a stereograph documenting a battle from the First World War. In the center, a high-end stereograph viewer, Le Taxiphote, from France. On the right, a stereograph camera used by Matthew Brady's studio. Courtesy, © 2013 Suzie Katz

Why war?

I think that part of learning is reconsidering how we think and what we think about — and our attitudes toward things. What we’re hoping is that, in engaging with the pictures and in reading the text, it will encourage people to think about the many different issues in this show:

When and why you go into war — and who it affects, and how they’re affected, and for how long they’re affected. The short-term and the long-term consequences of armed conflict. The courage, the heroics, the tragedies, the happenstance, the atrocities.

It’s a huge subject that most people don’t think about because it doesn’t really affect their lives. Or at least they think it doesn’t affect their lives. We just want people to be more aware of these wars that keep happening throughout civilization. It seems to be part of the human condition.

Divergent perspectives

It [has] photographs made by four different types of photographers; most exhibitions don’t include all those types. But we felt it was imperative, so there are military photographers; there are commercial photographers, which is both portraits and photojournalism. There are amateurs — soldiers’ snapshots, family snapshots. There are artists.

Each of those people has different clients, so to speak. The military photographers have a different mandate than the newspapers, than the magazine, than the portrait, than the soldiers photographing for themselves — and we try to acknowledge how for whom they’re shooting affects the resulting photographs in the catalogue.

The catalogue has a lot of history. It has a lot about the photographers. It has a lot about why they’re photographing and what they photographed. It has their biographies, so the catalogue is even bigger than the show; it’s 600 pages.

Our goal was to create something that is the beginning of discussions, not the end of discussions. We really feel like we’re introducing a lot of possible realms for future research. We hope people will take us up on it.

Some of [the veterans who have gone through the exhibition] have found it easier to talk — not directly about their own experiences, but on a secondary level — about their experiences.

Surprises from the research

I had to learn a lot of military history. I didn’t know any of that. I learned about the work of a lot of photographers I never previously learned about. As an American, I knew very little about the African civil wars because they weren’t covered. We weren’t in them. They weren’t [covered] except for Somalia.

[I] also had to learn about British and Canadian and Australian and German and Russian perspectives. And then, every photograph in the exhibition has a backstory. I mean, you can’t write a 600-page book without learning a lot.Lesser-known pictures

We have classic and famous pictures, like Robert Capa and D-Day, and pictures that essentially otherwise are previously unknown or little known, like a photograph taken during the Spanish Civil War of men who have are using dead horses are barricades. One of the real discoveries for us of was how great many of the Russian photographers are. [Dmitri] Baltermants, [Georgi] Zelma and [Yevegny] Khaldei, and other photographers were really great photographers, and are prominently featured in the exhibition. There are some photographers, like Don McCullin or Capa, who have more photographs because they photographed a lot of different combat and because they are just plain, great photographers.

We just went to military archives, Library of Congress, National Archives, museums, et cetera, and we just looked without a point of view. We just looked at as many photographs as we could find that had anything to do with war — and then images that we found powerful.

We began to build a database and worked from there. In terms of unknown images, there is a photograph by Robert Capa of two women ambulance drivers that are waiting to be called on their ambulance. They’re knitting, and the photographer Gary Knight made an interesting observation. He admired the photograph, and then he said [that] he might not have taken it because he wouldn’t have thought the newspapers would have published it — that he admired that Capa made a lot of pictures that didn’t make sense for normal newspaper or magazine to run.

When I read about these women medics, I became even more interested because [there] was a very high mortality rate [for] the women ambulance drivers. Medics and ambulance drivers are often direct targets because [combatants] figure if they kill a medic or an ambulance driver, they’ve killed two people. They’ve killed the person doing the rescuing, and the people that they’re saving. Medics are one of the most dangerous of the specialties.

It’s another example of something that looks sort of charming and a little bit sexist, these women knitting as they’re sitting. But, if you read the actual nature of their lives as an ambulance driver, it’s one full of danger. Almost every picture in the exhibition has that kind of a backstory.

Putting a light on civilians in wartime

We thought it was important to have a section of civilians because people when you say “war photography,” people don’t think about civilians. We also wanted to show the protest at home and abroad as a big part of war.

Civilians are impacted in many of the same ways as soldiers, except for actually doing the shooting. They are killed. They lose loved ones. They see the kind of violence that soldiers see. There is a horrific picture of a bus exploding in Israel. In fact, because of this picture the law was changed in Israel, and you were no longer allowed to photograph a scene like this until all of the bodies were removed. Because you can easily identify the individuals in this picture, and it’s just so tragic.

But we just wanted people to understand that, in the US except for 9/11 and the Civil War, we’ve been lucky. There is a picture of Somalia where there were so many people killed they had to turn the soccer field into a cemetery. Or in Bosnia, where people are digging up mass graves and looking through the body bags to try to find a piece of fabric or jewelry or anything that would identify a family member.

A lot more research needs to be done on soldiers’ snapshot albums, what they tell us and how they preserve the soldier’s point of view in conflicts.

On snapshots taken by soldiers

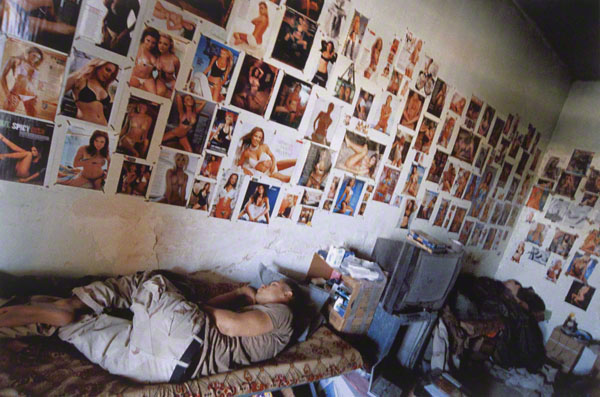

A lot more research needs to be done on soldiers’ snapshot albums, what they tell us and how they preserve the soldier’s point of view in conflicts. The first war to have snapshots is the Boer War, and we have all those images ever since. They haven’t really been studied. So, we’re hoping people will do that.

George Eastman invented the snapshot camera in the 1880s, and ever since, it’s been available to photographers. From the 1880s until the present, there are these marvelous collections of photo albums by soldiers. The Germans in both World War I and World War II actively encouraged the soldiers to photograph. They encouraged families to send cameras to the front, and there are some very large collections, private and public, of soldiers’ albums.

The albums give you sometimes a shocking view of the war. [For] some of the albums, there’ll be some quite disturbing pictures on one page — for instance a woman who has been raped or dead soldiers and dead animals. Then you turn the page, and they’re in a bar drinking or in the barracks horsing around. For those of us who have never experienced war that’s quite disturbing. But as one of the military historians said to me, “Anne, that’s their life. That’s what their days are like. That’s the kind of shifts they’re experiencing.”

There is an honesty and an immediacy in these albums that is very different than the kind of parsed-over histories of war written later by historians. It’s another reason why I really favor books written by the soldiers themselves because you get the view of somebody who lived it directly. And so, the albums exist. Unfortunately they’re also getting thrown away daily.

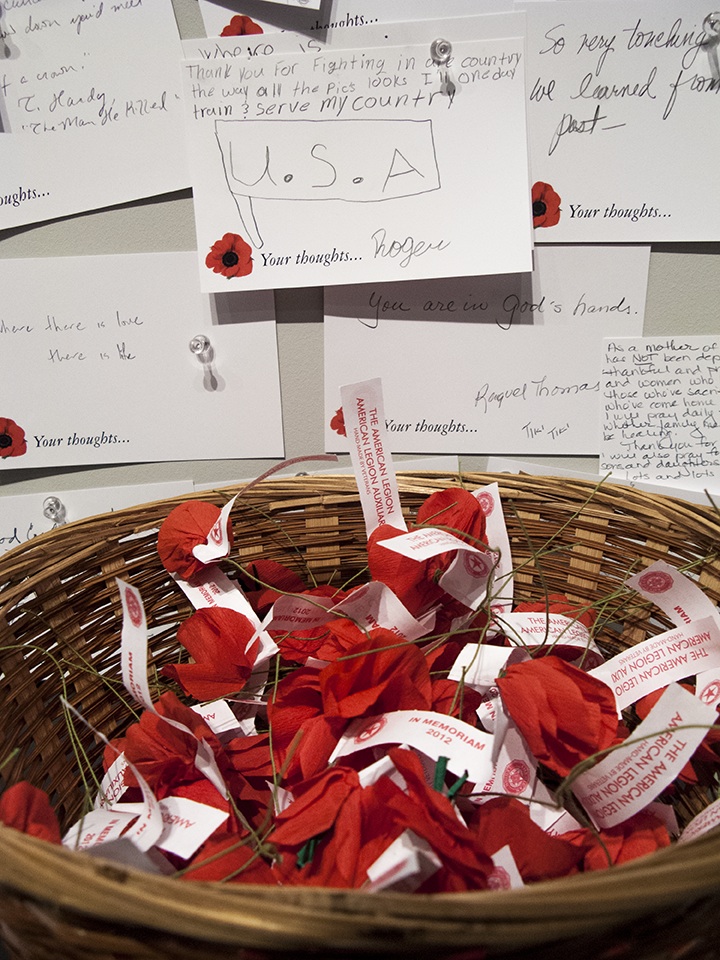

Soldiers’ reactions to the exhibition

Some of the veterans who have gone through [the exhibition] have found it easier to talk — not directly about their own experiences, but on a secondary level — about their experiences. If that talking has helped them, then I’m thrilled. You know, that’s a private matter. I’ve watched veterans go through the exhibition, but I have only talked to a few of them because I think it’s a very personal and private thing, their relationship with war.

A complicated relationship between soldiers and photography

I don’t know any example where, while they were in service, a photograph helped them. I know that they liked having them recorded. But on the contrary, I talked to a veteran of World War II who was injured. When he was in the hospital he threw away his camera, which he regrets now, but he threw it away because it had too many pictures of friends who were killed at the same time he was injured. I think, at the time, they have ambivalent feelings about photographs.

I think the power of photographs is to convey the experience of war to those who are not there, who aren’t fighting, who aren’t and will probably never be at the front — and subsequently as our collective memory, as history of what happened for generations that haven’t been born yet.

So would you rather protect her privacy or inform a nation about what is being done in their name?

Ethical dimensions of war photography

I think that there have been a lot of primarily academic discussions about whether photographers should photograph victims. I am not sympathetic.

I listen to any discussion, but I do get impatient with many of these discussions because does that mean we shouldn’t have photographed the Holocaust? Does that mean that we shouldn’t photograph Charles Taylor’s victims, and there are no photographs to use in his trial at the World Court? Does that mean that the people committing these atrocities should, in essence, win because there are no pictures taken of what they’ve done to whole villages, whole populations?

Now, I’m perfectly aware that some of these photographs have negatively affected the people in the pictures, and that is something to be aware of. The photographers are often aware of it. Many of these photographers have stayed in touch with the people that are in their pictures, and that are affected by them.

Eddie Adams and the general in the execution picture remained in touch until the general died, and Eddie Adams spoke at his funeral. Nick Ut and Kim Phuc have remained in contact for decades. Chris Hondros followed many of the people in his pictures until his death.

Yes, there is a price on the person in the photograph, the invasion of their privacy. But weigh that against the power of the picture. The picture Nick Ut took of Kim Phuc running down the road after she was burned by napalm changed public opinion about the Vietnam War. It’s a powerful photograph. So would you rather protect her privacy or inform a nation about what is being done in their name?

Emphasis on a common humanity

One of the things we consciously tried to do is show how the same experience crossed lines of combatants. We have a picture of American pilots waiting to be called up to go into action, and of German pilots waiting to be called up to go into action. They both had a similar, human experience of that moment where you don’t know if you’re going to land again or not. You know you’re about to go up, and you don’t know if you’ll come back.

It’s a picture of North Vietnamese soldiers reading the mail. Just below it is a very famous picture by David Burnett of [an American] Vietnam War soldier reading the mail. Again, we were trying to show that two opponents still share this human need for news from home. That’s one of the things that we try to convey over and over again.

This is a snapshot made by a soldier, of another soldier. It’s a photograph of a man who was in Iraq, and he longed for green grass. So, he made this little, tiny island of green grass, which he trimmed with scissors to just be able to put his feet in green grass. He was from Hawaii, so he desperately missed a bit of green. There is not a lot in Iraq.

We just wanted people to see that, when they’re not fighting, soldiers have lives. One of my favorite pictures is a man who is peeling onions with a gas mask.

And another big issue for soldiers, depending on where they are, is getting a bath. We actually have two pictures of bathing, but we could have had dozens and dozens. It’s an issue, and in Iraq they literally dig out a patch of desert and put sandbags and plastic down, fill it with water, and take a bath.

When you’re in a mobile unit during conflict, baths are hard. In Sebastian Junger’s really great book, War, about American soldiers in the Korengal Valley [in Afghanistan], these guys are in an outpost. The fighting was so intense they couldn’t get down to the base to bathe, and their clothes were so full of salt that the pants would stand alone. Imagine putting those on every day.

Navy Chaplain Lt. Commander Tom Webber baptizes Corporal Martinez in a sandbag-lined pool during a ceremony at Camp Inchon, Kuwait. March 16, 2003. Hayne Palmour IV, American, born 1957. Chromogenic print, printed 2010. The Musuem of Fine Arts, Houston, gift of Kevin Longino (1970-2011) © Hayne Palmour IV / North County Times

What can be learned from this exhibition

Most of us have never experienced and hopefully will never experience war. These photographs are our only visual access to what is being experienced by those who are fighting in or affected by conflict. If we’re going to be sending troops into a situation, it’s important to understand what we’re sending them into. It’s not all glory. It’s really difficult decisions and difficult, terrifying situations. Many veterans talk about war as just not what they thought they were going to experience, and they didn’t understand it.

We don’t understand it, and the only way we’re going to understand it is if we are exposed to the totality of this thing that is armed conflict. So, it’s important for those photographs to be gathered and the stories to be told.

There is a photograph in the exhibition of an Iraqi soldier who is burned to a crisp in his truck. He’s sitting totally charred in his truck, and someone said to me, “We didn’t do that. Americans didn’t do that.”

And I said, “Yes ma’am, actually, we did. We bombed the first truck. And we bombed the last truck. And then we strafed everything in between, and that’s what you do in war.”

What one military historian told me is, "In war, you kill the other side until they surrender. That’s the simplest explanation."

Images like that burned Iraqi are part of the experience. There is another image of a dead soldier who has been beheaded by a machine gun. It’s an exhibition that’s very difficult. The images are not just the images of dead and wounded, but some people are more even disturbed by a picture of children playing execution.

One of their little playmates is up against the wall like this, and the others are all kneeled, aiming their toy guns at him. It’s not what you’d like to see children playing. There is something different than children playing Cowboys and Indians — and actually playing execution where you’re shooting an unarmed person. But executions are part of war; there is a whole section in the exhibition. Many, many people die in wartime in executions.

We are trying to introduce as wide a realm of the experience of war as we could, through the best photographs that we can find.

Why photography?

When you read the written word, and even if the writer describes a person in some detail, we all come up with a different image of what they look like. The photograph is what they look like. Now, photographs are affected by words. They’re affected by the captions. They direct, misdirect or redirect our understanding of the photograph.

But the photograph has a power because we can recognize a moment, a situation, a human emotion in them that speaks to us in ways that words don’t.

These photographs are our only visual access to what is being experienced by those who are fighting in or affected by conflict. If we’re going to be sending troops into a situation, it’s important to understand what we’re sending them into. It’s not all glory. It’s really difficult decisions and difficult, terrifying situations. Many veterans talk about war as just not what they thought they were going to experience, and they didn’t understand it.

Interesting Links

- WAR/PHOTOGRAPHY at the Museum of Fine Arts Houston

- Extended trailer for the exhibition

- WAR/PHOTOGRAPHY at the Annenberg Space for Photography in Los Angeles

- Annenberg's video page featuring interviews with Ashley Gilbertson (a Foundry Workshop instructor), Carolyn Cole and David Hume Kennerly

- LA Times' review of the exhibition at the Annenberg

- WAR/PHOTOGRAPHY at the Corcoran Gallery of Art in DC

- WAR/PHOTOGRAPHY at the Brooklyn Museum

- New York Times' Lens blog post about the exhibition