Ken Light: Continuing the Photo Documentary Tradition in the 21st Century

Table of Contents

On Documentary Photography

The Evolution of Social Documentary Photography

The Power of Photography

On the History of Photography

On the Farm Security Administration (FSA)

Inspiration for a Book

The Publishing Process with Heyday Books

Behind the Scenes with Malcolm Margolin

A Book on Press

Getting a Book out into the World

Two Different Perspectives: Photographer and Writer

Looking From the Outside In: Developing Trust and Securing Access

Learn More About Ken Light's Book

Noteworthy Reviews

Big Ideas and Conversation Starters

Introduction:

Ripples from the recent economic downturn spread far and wide. Not since the Great Depression have the lives and stories of so many Americans been impacted in the collapse of financial systems. In the 1930’s, Roy Stryker sent out dozens of FSA (Farm Security Administration) photographers across the U.S. to make a permanent record of the times; in the process the FSA helped shape the history of the photographic medium. In the 21st century, Ken and Melanie Light continue that tradition of documentary storytelling.

Ken and Melanie Light were documenting lives in the Central Valley of California – the epicenter of foreclosures – before the economy tanked in late 2008. It was partly a case of right-place-at-the-right-time chance and partly their tenacity to pursue, doggedly, the issues unfolding. They have created a body of work that mirrors the concerns of the FSA nearly a century ago, and sadly shows us that social and environmental inequalities persist today.

Social documentary photographer Ken Light reflects on his work in the context of the history of documentary photography, his own influences, and shares his philosophy and process on image making. Light also discusses the nuts and bolts evolution of his project’s development - from concept and funding, through the publishing process, to exhibition and promotion. PhotoWings also goes behind the scenes at Heyday (Berkeley Publisher) and presents Ken’s video journal of his book on press in Singapore.

In this part one of a two-part feature, Ken Light discusses — in his own words — his career, photographic history and influences on his new FSA-inspired book project, Valley of Shadows and Dreams.

Click here for biographical information on Ken Light.

ON DOCUMENTARY PHOTOGRAPHY

The documentary tradition is—unlike a news photographer or even a magazine photographer who might go in and spend a day doing an assignment for a week or two weeks, doing a magazine spread—documentary photographers have traditionally evolved their storytelling over months and often years, going back, over and over, as time allows, and also being very independent.

The life, the commitment to documentary work for me has meant telling stories, looking deeply into the American psyche, looking at the country, the people, issues that have pulled me in - issues that I feel are important for people to understand - and witnessing the world around me.

As John Szarkowski said in his important book, Mirrors and Windows, Photographers are either mirrors or they're windows—either looking into the world or they're reflecting their own experience.

There have been a lot of influences in my life. Documentary photographers Jacob Riis, definitely Lewis Hine, Dorothea Lange, Walker Evans, many of the other Farm Security Administration photographers—war photographers W. Eugene Smith, and Robert Capa. Everywhere I look, there's an influence.

“All these things pushed on me, and somehow, I found refuge in the camera. The camera became a voice for me. It became a way to fight back. It became a way to cry out. It became a way to see my world and try to have a voice in it.”

THE EVOLUTION OF SOCIAL DOCUMENTARY PHOTOGRAPHY

Documentary photography has a visual tradition. If you look at documentary photographers over history, there are a lot of images of people looking directly into the camera, so that the viewer looking at the photographs now—20 years, 50 years or a 100 years from now—will feel that there is some sort of a very personal connection between the person in the photograph and the viewer. The idea of showing the environments, the social landscape as being part of the tradition, the reportage of people doing things, of what are their lives and world are about, trying to create an intimacy with the subject and going inside of that.

Every photographer has done it differently, has pushed the envelope, has tried to find a new way of seeing visually, but I think there definitely is a thread from the very beginning, if you go back and you look at the work of Thomas Annan, Streets of Glasgow, for example, Jacob Riis, Lewis Hine, the list goes on of photographers who have worked in this tradition who have been visual storytellers with a camera.

"Part of what has helped me and I think probably what has helped other documentary photographers, is that the worlds that we enter, the people that we meet, the communities that we photograph, usually are unseen."

THE POWER OF PHOTOGRAPHY

“Everything has been photographed in the world. It's just a matter of every generation of photographers reinterpreting it, seeing it in a new way.”

I think of my experiences as a young boy growing up in New York. My grandfather had a store in Spanish Harlem, at 116th street. I used to go into work with my father, who worked there selling furniture at my grandfather's store, and the street was incredibly alive. I would maybe describe it as a Helen Levitt or Walker Evans photograph, with all types of people who are outside of my own world. I was growing up, at that point, in a very white-bread suburban community, where there were absolutely no minorities: the bedroom community of New York City. So to go into Harlem and to see the energy, and the people, and the strife, the struggle, the poverty, and the street life as a young boy was a really incredible experience.

I think, partly, that experience of seeing Harlem, and then just being informed, and growing up in a time in America in which things were very tumultuous has shaped me as a photographer; we saw the civil rights movement, the assassination of President Kennedy, the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., the assassination of Malcolm X, and Robert Kennedy. The beginning of the '60's, the pushback against the Vietnam War, of young people finding a new culture, of long hair, of my generation trying to have a voice in their world.

Ken Light talks about his photographic process and his home darkroom. Courtesy, ©Suzie Katz 2012

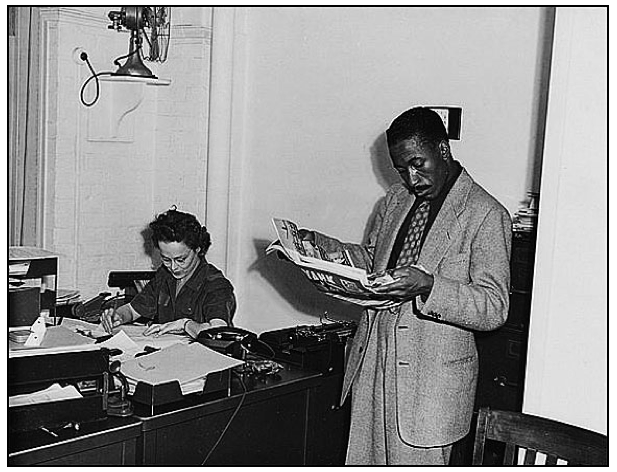

Gordon Parks, FSA/OWI (Farm Securities Administration/Office of War Information) photographer circa 1943.

Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, unknown photographer

Ohio University had a photography department that had a very strong program. On the day of Park's visit, we had organized a huge anti-war rally, which was in the school's gymnasium, and there were probably thousands of people. I'll never forget Gordon Parks wanted to see it and he wanted to come over and he wanted to talk. It was a remarkable moment for me as a young photographer, just getting his start in the world, to see this amazing photographer— amazing human who is incredibly talented— get up in front of this group of young students, radicalized by what had happened at Kent State and fighting against the war and fighting against injustice, and having this incredibly articulate man get up and give the power fist, first of all, which was quite an experience and then talk about the world—not just about photography and the world.

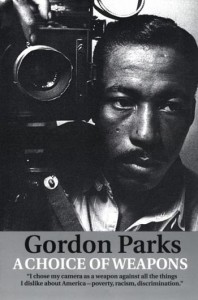

"Gordon Parks talked about how the camera, for him, was like a gun, a weapon, which is an incredible way to think about the camera."

It was really fascinating for me because I knew the work of Gordon Parks at LIFE magazine. But I didn't know anything about him as a person. I knew him through his photographs—the Great Depression photographs he took when he was working as part of FSA, and many stories in LIFE magazine, particularly about poverty in Latin America. There are many, many photographers out there who have been wonderful influences and also whose work my own photography has referenced. There's never a sense that your own world is very exciting, and you need to understand that everything changes.

"We need to learn to photograph in our own time, in our own world, because that will change.”

Book cover of Gordon Parks' 1986 autobiography, A Choice of Weapons

ON THE HISTORY OF PHOTOGRAPHY

"I think what I've learned is that every generation of photographers is built on the previous generations. And the more I did photography, the more I learned."

At the very beginning, I didn't even know that there was a history of photography. You feel like you're inventing it yourself, and then you realize there's an incredibly deep history of photographers doing important documentary projects which sometimes aren't seen because they haven't been published in books or they weren't. At the very beginning of my career in the early '70s, I was being exhibited in museums. My images weren't being published in the magazines, but they were being created.

One of the wonderful things about photography that you learn eventually is we have a history, that you're not the first one. When you really start to read about the history of photography, you begin to realize there have been people decades and decades before you who had the same issues, the same concerns, [and who] photographed the same things.

"Something that is important to me is discovering who these photographers were, what they did, what their work was about, and learning from that work, and looking at it."

I'm basically a self-taught photographer. I learned from looking and sitting, scrutinizing books, thinking about it, and talking to friends who would share what they knew and then building on that base. Knowing about these other photographers and their work and their passion has really been an important part of my own path as a photographer.

ON THE FARM SECURITY ADMINISTRATION (FSA)

To learn more about the FSA, read our 'Library of Congress' feature

SEE ALSO: Ken Light - "Depression Deja Vu," Newsweek

I think one of the most important periods in documentary photography in the U.S. was due to the Farm Securites Administration. The FSA was a division of the Department of Agriculture, and it was set up to document the conditions of farmers during the Great Depression. During the Great Depression, farmers were hit not only by incredible drought and poor farming practices, they were also were hit by bank foreclosures, loss of their land, [coupled with] their inability to raise capital to buy seed and equipment. And many of them were thrown off the land. Their conditions were horrific and we read about what the Arkies and Okies described, who left their land for these reasons, and who headed to California.

The FSA and this work had been a great influence on me. The photographs made by Dorothea Lange, Walker Evans, Marion Post Walcott, Jack Delano and Arthur Rothstein [for the FSA] depicted this era and these people. They fanned out throughout America on assignment, and the idea was to create a visual image so that people might understand what—as we would say today—what the 99 percent doesn't have— and what their world is about. And Roy Stryker, who was a director of the program, was incredibly talented in selecting this group of young FSA photographers. Of course, they turned out to be some of the greatest photographers in the canon of photography.

John Steinbeck set out to write this story for LIFE magazine with the photographer, and after some travels, Steinbeck decided, "Who needs LIFE magazine? I'm going to write my own book. I don't need it." He ended up, from that experience and those travels, writing the great novel The Grapes of Wrath, which looks at a fictionalized family—Okies and Arkies—leaving after their land is foreclosed and traveling in a broken-down Depression-era truck—we've seen those pictures—into California and then finding in California there was actually no work and what that life was about, and it was made into a really great, amazing film, [and] that is still read in school.

I can't tell you the number of people that [have] sent me e-mails that said, "We need to start up a new FSA. We need to put together a team of documentary photographers who could go out and document the plight of what is happening in America." They just want the resources. It really has been dependent on individual photographers who maybe have decided to do a little piece of it— to do something about foreclosures. There's no major project in which major photographers have been assigned to go out and record this moment. And it's unfortunate, because I think the power of the photograph—despite the fact that we are in the Internet age and sound is important and multimedia is important—the still photograph has an important place.

"I think the still photograph has an important voice in informing people, and it allows people to stop for a minute. We've become such a 24/7 moving world with a constant stream of news and sound and pictures. And the wonderful thing of a still photograph is you get to linger, you get to stop, you get to look, you get to think, you get to react, and it is a very different experience."

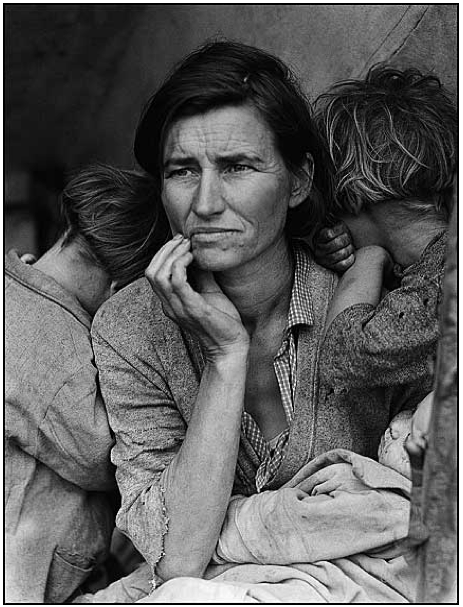

It's interesting to think about Dorothea Lange's Migrant Mother image, which I think is one of the most iconic images of the 20th century, and it's an image that has very deep, humanistic feelings and message asbout the world and particularly about the Great Depression in the United States.

Destitute pea-pickers in California; a 32-year-old mother of seven. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, 1936

"And you begin to wonder, what if she had lived in a multimedia age? Would we have that iconic image? Would the image be different if the migrant mother was talking?"

What if Dorothea Lange was out there with her Canon 7D and her Røde sound-mic on top and her little flash card, and she comes across this family - what do you do? So, she'd be explaining why she was there, and the children were talking, and it was video rather than a still image. How would we relate to that experience? I think we would relate very differently. We're looking at this, and each of us brings our own experience of maybe what it would be like to be this mother in this situation, under this lean-to, during the Great Depression. How would our children behave? And what would we do?

"[These FSA images] were very important in bringing change and making people aware that this issue even existed. Photography has played a really important part as social witness in its own time—in the age of the photographer doing this work. But also as a social witness historically, because ideas and social movements and the conditions in which people live, often seem to disappear in history."

And if it wasn't often for these photographs— seen in history books now, and in publications— many younger generations who did not grow up hearing these stories, did not grow up knowing that child labor was part of the fabric of America, and they didn't know what the immigrant experience was like in earlier generations. We're really dependent on these photographs now, to share, fully share, visually share, what these worlds and what these lives were about, and that witness I think is really important.

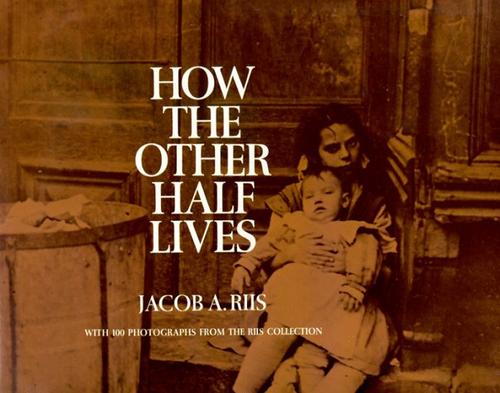

Book cover of Jacob Riis' 1890 book, How the Other Half Lives, which portrays poverty in the New York City Mulberry Bend Slum.

INSPIRATION FOR A BOOK

Jacob Riis’s book, How the Other Half Lives,was one of the early books that combined the text and reproduction with ink on a sheet of paper and [was] distributed. That book was a very, very important book, because no one had really seen what was happening in the Mulberry Bend slum[in New York City] and the living conditions of the people and what their lives were about. There’s something about seeing an image, there’s something about the power of it, people being inside the environments which were photographed—the drunk tanks in the jails, the bandits roost, the dives in which he photographed, the portraits of the blind man on the street selling cigars, the improvised children—that was seen and then heard by politicians.

[Lewis] Hine as well, photographing social images, is well known for his images of Ellis Island. And his photographs of immigrants coming through Ellis Island into America are some of the most important records of the diaspora of many different cultures and people coming again [from] Europe—the Irish, Jews from Eastern Europe, Slovakians and so forth—coming to America to look for a better life. These photographs remain an important document of what that experience was like. One of my favorite bodies of work of Hine are his photographs of child labor."Theodore Roosevelt was then the Mayor of New York State, and he and his aides were taken back by what they saw, and it began the major project of redeveloping the Mulberry Slum, which was a slum in which immigrants found themselves after coming from Eastern Europe and (other) parts of Europe to make a better life in America. So it had a very powerful impact."

We all know, of course, Dorothea Lange's The Migrant Mother, which singularly depicts, the conditions that many people found themselves in, in the Great Depression. So this work for me has been a great influence. And it is fascinating to think about the relationship between their work and the work that I have just completed with my wife Melanie Light.

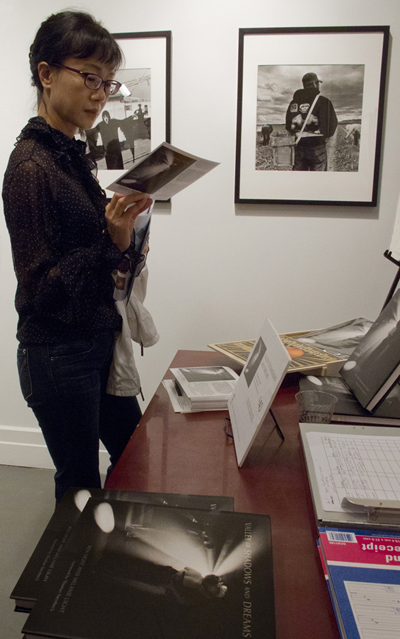

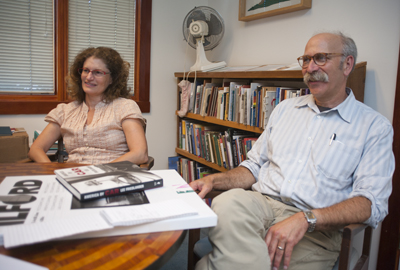

Ken and Melanie Light meet at Heyday in Berkeley, to discuss publishing Valley of Shadows and Dreams. 2010 Courtesy, ©Suzie Katz

And it really was Melanie who came to me before the downturn and said, "There's this stuff happening in the great Central Valley in California that we really need to look at. You should stop what you are doing." And at that point, I was photographing in the Great Plains. "You should stop what you are doing, and you should really go into the Valley because it is incredible."

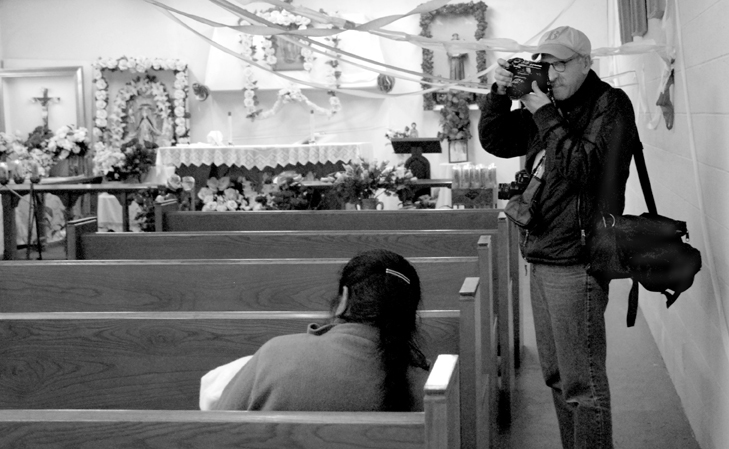

Ken Light in a church photographing the Posada (a Latin American Christmas Festival) in Toneyville during the creation of Valley of Shadows and Dreams. Photo by Allison Light. Courtesy, Ken Light 2007

It is incredible to see this rich agricultural land being paved over and suburban houses being built. Who can afford these suburban houses? How people can commute to these suburban houses? Where is the water going to come from for the washing machines and the dishwashers and the sprinklers that are going to water their lawns? There are water issues in California. We were in a major drought already. And so having just come from collaborating with her on our book Coal Hollow, I was intrigued. And her voice is very powerful. So I went into the Valley, and I began to see what she was describing.

"I come in with great curiosity. I just think being behind a camera is one of the great gifts that can be given to you, to enter people's lives and see what their world is about."

It’s fascinating to think about the modern culture and how reality TV shows have become so big on television and that’s because people like to sit and look at other people’s lives, what these other realities are. Fortunately for photographers, we’re there. We’re inside these stories. We’re on death row. We’re on the border with border patrol agents as they’re apprehending people coming though the fence. We’re at a river baptism in rural Mississippi. We’re out in the field as people are picking crops.

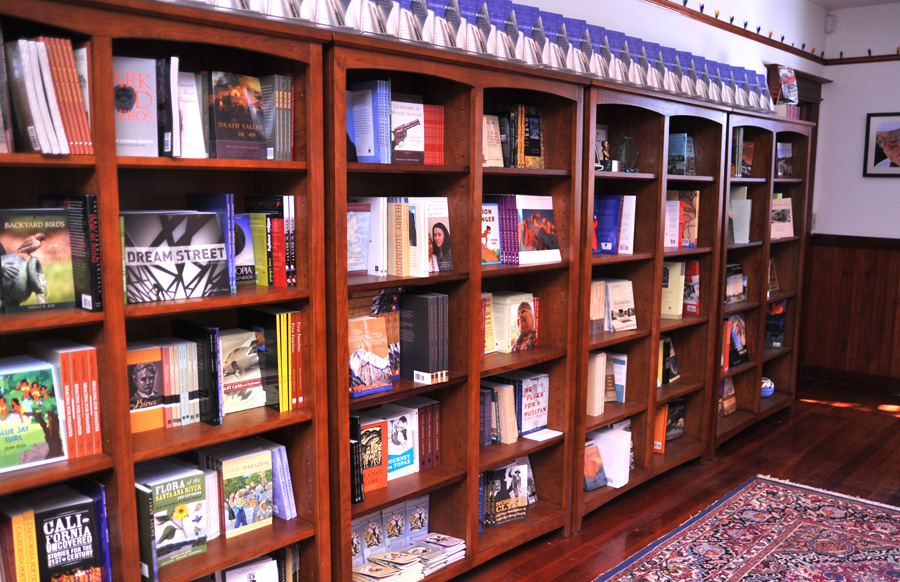

Heyday, located in Berkeley, CA, has been in business since 1974 and publishes over 24 books a year. Courtesy, ©Suzie Katz 2011

THE PUBLISHING PROCESS WITH HEYDAY BOOKS

"I think books are really important. I think rediscovering work is really important—making sure that work doesn't disappear, because there are many photographers who have done incredibly brilliant work that sadly disappears or gets locked into the vaults of museums, which on one hand is good because it is protected, but really, this work needs to be seen out in the world."

BEHIND THE SCENES WITH MALCOLM MARGOLIN

"When Ken and Melanie came in with their manuscript, it was a shock to me." says Malcolm Margolin, executive director of Heyday, "It was a shock to me because this was a valley that I had tried to avoid. This was a valley that I didn't want to see. This was the elephant in the room. This was the valley that was cruel. This was the valley that was exploitive. This was the valley that was destructive to land.

"In some ways, I had a sense of relief; that at last somebody was going to tell the story. They were going to tell the story with a bigness, and they managed to do it because they had a bigness to them.

"There's a kind of outrage in this book, and there's an outrage that you usually find in younger people. Usually people get co-opted. They get professorships at universities. They lead a softer life. They begin to compromise.

"There was something else that was kept alive and kept sustained, and yet it was wedded to the highest forms of art, and the highest forms of craft, and the greatest possible experience. I think of Ken as young, but he's been publishing books for over 30 years now.”

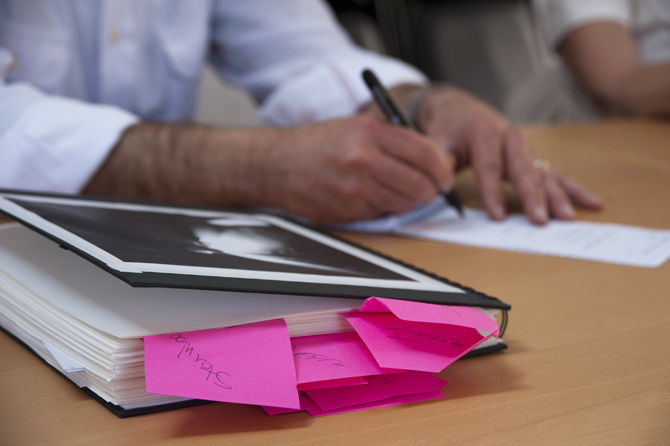

Ken and Melanie Light meet publisher and founder, Malcolm Margolin at Heyday discussing publishing Valley of

Shadows and Dreams. Courtesy, ©Suzie Katz 2011

Shortly after going into the Valley, we were hit by the economic downturn. It was an incredible time, the last four-and-a-half years of doing this body of work. And I found myself with Melanie having our own little mini-FSA project, initially funded by a very small grant from a private foundation that had done work in the Valley, that was interested in conditions in the Central Valley with no strings attached. [The Rosenberg Foundation] basically said, “Here’s $10,000. Why don’t you go see what you’re going to see.” And we pitched the idea that we would do a book.

An early mockup of Valley and Shadows and Dreams is flagged on the desk during a publishing meeting at Heyday. Courtesy, ©Suzie Katz 2011

To put together a project, as I’ve been describing, becomes very difficult. We wanted to do a book, and that created another problem. One of the wonderful things is that there is this small-knit group of people who love photography, who love the voice of photography, who want to tell these stories, who want to get it out. Luckily, PhotoWings stepped in and helped create the book, support the book, [and is] one of the biggest contributors to the creation of Valley of Shadows and Dreams. And amazingly, Thomas Steinbeck, John’s eldest son, was pulled into the project and wrote about his own experiences in the Central Valley and what he saw.

We spent the next four-and-a-half years working together, and me working individually, going into the Valley and meeting people and photographing and trying to examine what was happening there.

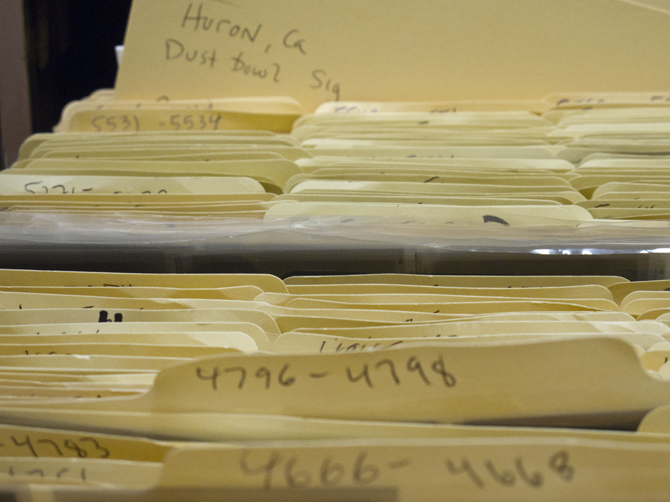

File folders full of photographs, negatives, model releases, caption notes, and other important documents fill Ken Light's filing cabinets in his home darkroom. Courtesy, ©Suzie Katz 2011

Of course, the Central Valley ended up being one of the epicenters for foreclosures in the world that has created the economic downturn that we’ve seen in for these last four years. But we wanted to go beyond that.

“We wanted to tell a bigger story, because the story of the Valley is really the story of what is happening in a lot of the world, places where there are extractive industries that go in, that pull out.”

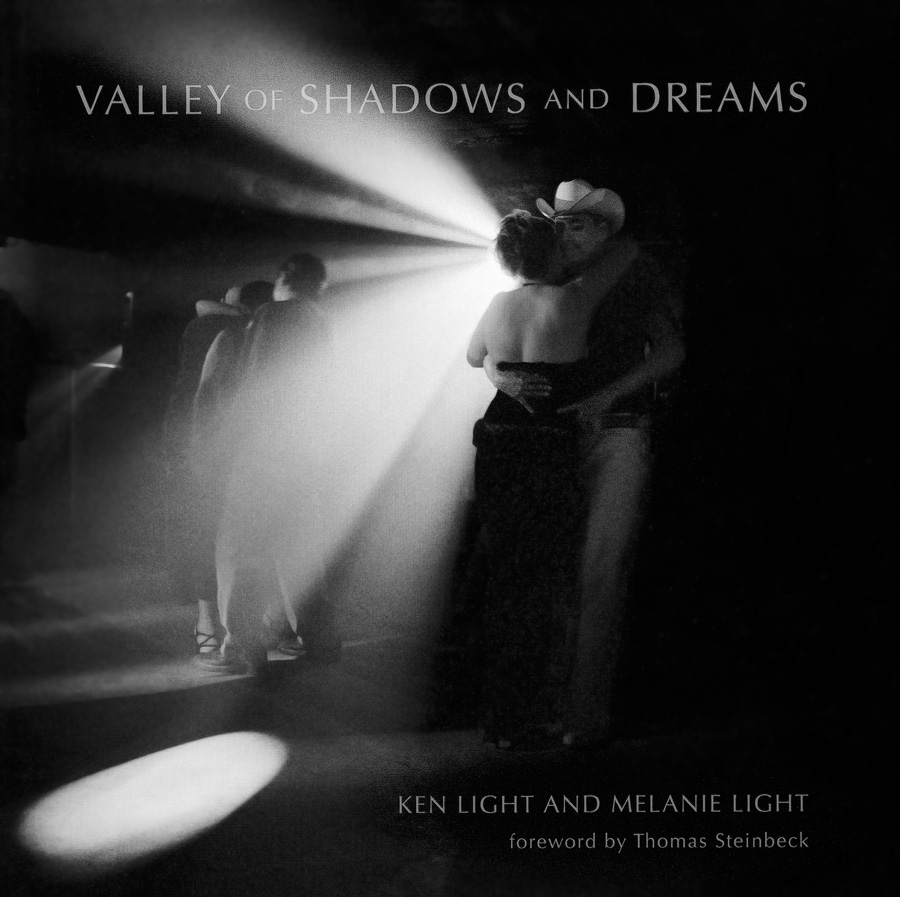

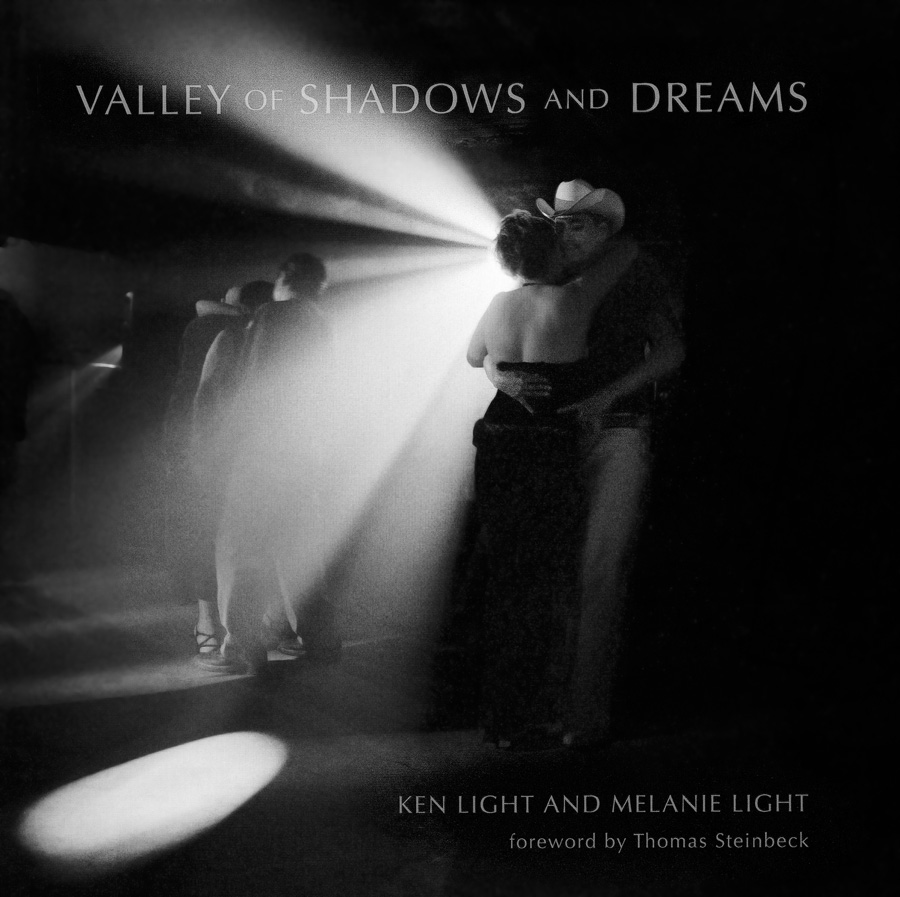

"Midnight, Fiesta Club," Cover image for Ken Light's book, Valley of Shadow and Dreams. Courtesy, ©Ken Light 2007

For the Valley of Shadows and Dreams, we’ve committed four-and-a-half years of writing and making photographs and a year-and-a-half of raising money and working with the publisher, Heyday, to do the book we wanted to do. In a book, you’re trying to represent the time - and there are all different moments. The cover image, 'Midnight, Fiesta Club,' has become a very popular picture that people are really drawn to. Of course, it really, in a way, unbeknownst to me in making this photograph, represents the shadows and dreams, which is what this book is about.

"It is about the dreams that people have coming to the Valley, which is the first stepping-off point for many people who are new immigrants coming from Mexico and other places in Latin America, moving up—trying to move up the ladder into a better world with their families, and also the shadows, the disappointments, the dangers."

This photograph shows both of those things—the shadows and the dreams. The dreams of a better world and a better life. We hope that this book adds a voice to these issues, to these problems in California. That helps define and relate to other issues in the other parts of the world, issues around water rights, industrial agriculture, foreign workers, and pesticides. This work is also about the human condition and about people like us and what their world is about and, in a way, why we should be thankful for what they do for us.

“We hope to honor the subjects, and also the hard truths that we discovered in the Central Valley.”

Ken Light - Video Journals On Press - PhotoWings Exclusive from PhotoWings on Vimeo.

A BOOK ON PRESS

In December 2011, PhotoWings asked Ken Light to document the book printing process for his new book, Valley of Shadows and Dreams. Ken made a video journal of his book “on press” in Singapore, documenting the printing process and the exhausting amount of energy and emotion involved. Since the book is on press 24/7 the photographer needs to wake up as each page comes through to check for errors, which Ken discusses. PhotoWings has edited a long and shortened version.

GETTING A BOOK OUT INTO THE WORLD - PROMOTION, EXHIBITIONS, LECTURES

"The idea is to create a voice with this work. Long after you finish making the photographs, I guess, this is another thing that documentary photographers do—they are committed to getting added to the world".

You spend time telling people, lecturing, trying to get pictures onto websites, doing exhibitions. It really is a whole job by itself after the pictures stop, to get these things out into the world, which is an important part of the practice.

We want people to say it is not that way now. I was at a photography conference at UC–Santa Cruz, and I was one of the guest speakers, and I showed the Valley work and talked about it. A young woman photographer from Fresno got up in the audience and was angry with me. She said, "You're gonna kill Fresno as a tourist destination," which in itself was kind of funny, and she just went on to tell me how mad she was at my photographs. It was great.

"And that, to us, is what we do. We're troublemakers. We want to tell stories. We want to investigate. We want people to be upset with us."

TWO DIFFERENT PERSPECTIVES: PHOTOGRAPHER AND WRITER

Sometimes, Melanie and I look at each other and wonder if we are just totally crazy. We’ve invested so much time, energy and love into doing these projects. But it’s what we do. And it’s what I’ve done for over 40 years. And I think every new project has just been very exciting to figure out, to enter in, to bring to fruition, and then use the work as a way of telling these stories.

“So we’re already five-and-a-half years into this body of work, and now we’re going to spend probably another year trying to get the work out into the world. I think in all my work, I keep going back to this voice—whether it is hearing the voices of the people I photograph or my own voice—and I think of this work. The issues in the Valley are so important, what’s happening there, and they are so relevant to what’s happening around the rest of the world, and the rest of America—the conditions that people find themselves [in] and their stories, the issues around water, the issues around pesticides, the issues around industrial agriculture, foreign workers, undocumented workers. These issues are there and everywhere in the world.”

Ken and Melanie Light speak in Berkeley during a their UC Berkeley opening reception. They share stories and photographs from their book, Valley of Shadow and Dreams. Courtesy, ©Suzie Katz 2012

Guests view Ken Light's photographs, "Land," "Midnight, Fiesta Club," and "Food Line," at his opening reception in Berkeley. Courtesy, ©Suzie Katz 2012

Guests view Ken Light's photographs, "Land," "Midnight, Fiesta Club," and "Food Line," at his opening reception in Berkeley. Courtesy, ©Suzie Katz 2012

Visitors enjoy looking at Ken Light's photographs "Sign With Bullets," "Rope Swing," and "Tule Fog" during his opening reception in Berkeley, California. Courtesy, ©Suzie Katz 2012

LOOKING FROM THE OUTSIDE IN: DEVELOPING TRUST AND SECURING ACCESS

I think the challenge of doing documentary project is how do you get inside the circle of people's lives? How do you meet people? How do you tell their stories, particularly, in environments where you're an outsider? All my projects have really been about being an outsider, except probably my earliest work as a young photographer photographing my own world of the '60s. So I've always been an outsider.

"This is the purpose of why we do this work, and why we invest the time, and why we struggle to raise the money, and why we are out in the field photographing, and why Melanie is sitting in front of the computer writing and interviewing people. We think these are important stories, and we don't let them just slide into the world unnoticed. We want to be a part of this conversation. We want our voices to be heard. And we want the people we photographed, for their voices to be heard."

This is one way for their voice to be heard, by their image [being] represented visually and for people to see them and wonder what their stories are about.

People who I've met two minutes ago say to me, "You need to come in my house, because there's a hole in my ceiling, and you need to take a picture of it because someone needs to see it." And so my experience is doing documentary work and my experience in the Valley is that people were incredibly, incredibly open to sharing their worlds and to connecting me to other people. And so very often, I go down to the Valley and I would call someone. I would say, "Hey, this is Ken, I have just arrived. Do you have some time?"

“And my god, these people were so generous and literally, for a tank of gasoline, they would drive me around. They would spend hours with me. We could talk about what I was seeing. I could ask them questions.”

They would take me to people’s houses. They would vouch for me, which is so important for someone to say—when an undocumented family who speaks no English, who had great fears about the immigration people coming to get them, who were fearful of being discovered—and there you are with the camera, having this person basically say, “He’s a good guy. He’s doing this story. You should be in it. You should show him what your world is about.”

Those kind of contacts are incredibly, incredibly important. And then I think you spend a lot of time just going with your own instinct, just being very, very observant, watching all the time, having in your head a little list of the things that are important.

“A sacred trust involves not only telling their story and getting out their story, but also protecting their images in the world—how those pictures are used and what is said about them and creating a powerful image”

In some way is true to what you have observed and what they have told you about their experience. And I think that they push us. They allow us to pull ourselves together and do our work and realize that we’ve made this commitment to tell these stories, and we are going to do it, whatever the cost.

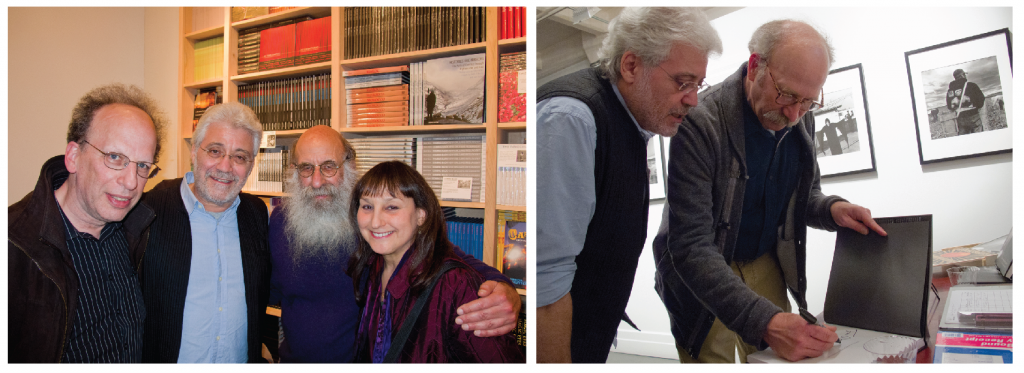

Left: Attending Ken and Melanie Light's New York exhibit and reception at Umbrage Books, Fred Richin (NYU & Pixel Press), Robert Pledge (Contact Press Images), Malcolm Margolin (Heyday Publishing), and Suzie Katz (PhotoWings) pose for a photo. Right: Ken Light signs a book for Robert Pledge, founder of Contact Press Images, at Ken's opening at Umbrage Books. Courtesy, ©Suzie Katz 2012

BIG IDEAS AND CONVERSATION STARTERS

A Record of the Times

"There's never a sense that your own world is very exciting, and you need to understand that everything changes. We need to learn to photograph in our own time, in our own world, because that will change."

The Power of Photography

"Everything has been photographed in the world. It's just a matter of every generation of photographers reinterpreting it, seeing it in a new way."

Learning from the Past

"I think what I've learned is that every generation of photographers is built on the previous generations. And the more I did photography, the more I learned.

"At the very beginning, I didn't even know that there was a history of photography. You feel like you're inventing it yourself, and then you realize there's an incredibly deep history of photographers doing important documentary projects which sometimes aren't seen because they haven't been published in books or they weren't, at the very beginning of my career in the early '70s, being exhibited in museums. They weren't being published in the magazines. But they were, in fact, being created."

The Importance of Photography Books

"A book is an object that lasts for a very, very long time and it is an important record. It goes into libraries, it goes into people's collections, it passes from one photographer's hands to the next."

Photographers as Part of the Conversation

"That, to us, is what we do. We're troublemakers. We want to tell stories. We want to investigate. We want people to be upset with us."

Working With the People you Photograph

"They would drive me around. They would spend hours with me. We could talk about what I was seeing. I could ask them questions.

"They would take me to people's houses. They would vouch for me, which is so important for someone to say—when a documented family who spoke no English, who had great fears about the immigration people coming to get them, who were fearful of being discovered—and there you are with the camera, having this person basically say, "He's a good guy. He's doing this story. You should be in it. You should show him what your world is about.""

The Relationship Between Photographer and Subject

"A sacred trust involves not only telling their story and getting out their story, but also protecting their images in the world—how those pictures are used and what is said about them and creating a powerful image" that, I think, in some way is true to what you have observed and what they have told you about their experience.

"And I think that they push us. They allow us to pull ourselves together and do our work and realize that we've made this commitment to tell these stories, and we are going to do it, whatever the cost."

Dedication to Your Work

"Sometimes, Melanie and I look at each other and wonder if we are just totally crazy. We've invested so much time, energy and love into doing these projects. But it's what we do. And it's what I've done for over 40 years. And I think every new project has just been very exciting to figure out, to enter in, to bring to fruition, and then use the work as a way of telling these stories."

Giving a Voice to the Voiceless

"So we're already five-and-a-half years into this body of work, and now we're going to spend probably another year trying to get the work out into the world. I think in all my work, I keep going back to this voice—whether it is hearing the voices of the people I photograph or my own voice—and I think of this work. The issues in the Valley are so important, what's happening there, and they are so relevant to what's happening around the rest of the world, and the rest of America—the conditions that people find themselves (in), and their stories, the issues around water, the issues around pesticides, the issues around industrial agriculture, foreign workers, undocumented workers. I mean, these issues are there, everywhere in the world."

Believe in Your Work

"My experience in the Valley and in other projects I've done is that people put an incredible amount of faith in what it is you are going to do. And so I've had people pull me into their houses, people who I don't even know."

Photographers as Role Models

"I would go visit this family pretty much every trip I made into the delta, after having met them. The mother would always use me as an example of how her son could do something with his life. It was fascinating, like, "Here he is. He's a photographer. This is something good. You could be a photographer. You could be out in the world. You shouldn't be getting in trouble. There are a lot of things you can do. Look at this guy. He's interested in us. He's interested in you." I was kind of a positive role model. It was really fascinating, and I remember when I came back four, five months later, he'd been arrested and he had gotten trouble. He had been with a bunch of friends who were robbing a house. They went in, they broke into a house, and he was the lookout. They escaped out the backdoor, and they left him standing there, and he got arrested, and he was going to be before the juvenile authorities in Mississippi. The mother just kept saying, "You should go to school. Look at this photographer. There are a lot of possibilities." It was just really fascinating to see that, obviously, my being there and my interest in the family and my interest in the young boy was something that she saw as really positive. So I think photographers can (play) a positive role in how people see them, within the families and in telling their stories."

LEARN MORE ABOUT KEN LIGHT'S BOOK

Valley of Shadows and Dreams - Offical Book Website

This website is home to Ken and Melanie Light's book project. The site features project details, images, excerpts from the book and additional resources about the Central Valley.

Ken Light - Official Website

Browse through photo galleries from Ken Light's extensive portfolio, including publications, stock images, biographical information and more.

New York Times - The Vanishing Valley, by Ken and Melanie Light

Contributed opinion text from Ken and Melanie Light, May 2012

San Francisco Chronicle

Ken Light sits down for an interview with Sam Whiting of the San Francisco Chronicle

AGree

AGree is a new initiative that brings together a diverse group of interests to transform U.S. food and agriculture policy so that we can meet the challenges of the future.

American Farm Bureau

Farm Bureau is an independent, non-governmental, voluntary organization governed by and representing farm and ranch families united for the purpose of analyzing their problems and formulating action to achieve educational improvement, economic opportunity and social advancement and, thereby, to promote the national well-being.

California AgVision

In 2008, the State Board of Food and Agriculture inaugurated California Agricultural Vision (CAV) as a process intended to result in a strategic plan for the future of the state’s agriculture and food system.

California Institute for Rural Studies

CIRS is the only non-profit organization in California with a mission to conduct public interest research that strengthens social justice and increases the sustainability of California’s rural communities.Their work informs public policy and inspires action for social change while providing a fact-based foundation for organizations and individuals working to ameliorate rural injustice.

Center on Race, Poverty and the Environment

The Center on Race, Poverty & the Environment is an environmental justice organization dedicated to helping grassroots groups across the United States attack head on the disproportionate burden of pollution borne by poor people and people of color. We provide organizing, technical and legal assistance to help community groups stop immediate environmental threats.

Environmental Working Group Farm Subsidy Database and The Environmental Working Group

The mission of the Environmental Working Group (EWG) is to use the power of public information to protect public health and the environment. Great links to related topics:

Great Valley Center

The mission of the Great Valley Center is to support activities and organizations that promote the economic, social and environmental well-being of California’s Great Central Valley.

Roots of Change

Roots of Change brings a diverse range of Californians to the table to build a common interest in food and farming so that every aspect of our food—from the time it’s grown to the time it’s eaten— can be healthy, safe, profitable, affordable and fair.

NOTEWORTHY REVIEWS

"I think Ken has made enormous artistic (emotional, intellectual) strides here, and has been able to translate the visual ideas of the FSA (Farm Security Administration) into a new, more complex, psychological vocabulary for our present times. I think these are some of the best pictures made in California today because he is not following the familiar conventions of FSA photography but has used them to advance those ideas and create something new and important. I don't think they would be as moving or as important if they were in the FSA mode."

- Sandra Phillips, Senior Curator of Photography, SFMOMA

"...the book's bleak vista encompasses compassion, loyalty, resilience, resistance and even humor. Page after page of black-and-white imagery places the book aptly in the lineage of Walker Evans, Dorothea Lange and Robert Frank."

- Kenneth Baker, San Francisco Chronicle

Read Baker's full review of Valley of Shadows and Dreams here

“In some ways, I had a sense of relief; that at last somebody was going to tell the story. They were going to tell the story with a bigness, and they managed to do it because they had a bigness to them.”

- Malcolm Margolin, Publisher at Heyday Books